First Person Point of View

In First Person Point of View, the Narrator is a character who exists within the story world. They use first person personal pronouns to describe… Read More »First Person Point of View

In First Person Point of View, the Narrator is a character who exists within the story world. They use first person personal pronouns to describe… Read More »First Person Point of View

The mystery genre requires careful threading of information from character to character, between narrator and reader, and from author to audience. And Agatha Christie, as… Read More »The Misdirection of Agatha Christie | Liar, Liar

Continuing in the Cooperative Principle and how to break it, we turn our attention to a literary example of rampant unintentional violations: Miss Bates from… Read More »Miss Bates of Emma: A Liar, Liar Case Study

If my most recent works haven’t been clue enough, I’ve been doing a lot of writerly experimentation with point of view and perspective. Hence the… Read More »Julian St. John Audley: A Character Defense

When it comes to dangerous artifacts in a fictional setting, every writer faces at least two dilemmas: Why does everyone want this thing? Why is… Read More »Dangerous Artifacts and the Characters Who Love Them

When it comes to Regency Romance, there is one name that stands out as the paragon of the genre, at whose altar all other Regency… Read More »Regency Romance: The Grandmother of Guilty Pleasures

(Did it work? Do I have your attention?)

Beowulf is one of those works of literature that, quite honestly, never interested me. Some beefy warrior kills a monster, and then he kills another one, and there’s a dragon in there somewhere, and at the end (spoiler alert!), he dies. I maintained a scornful disinterest for this epic over the course of a decade, until my conversion in my mid-twenties. Here’s how it went down.

“Melancholy men, they say, are the most incisive humorists; by the same token, writers of fantasy must be, within their own frame of work, hardheaded realists. What appears gossamer is, underneath, solid as prestressed concrete. What seems so free in fantasy is often inventiveness of detail rather than complicated substructure. Elaboration — not improvisation.” ~Lloyd Alexander, “The Flat-Heeled Muse”

When it comes to fantasy, everyone has a starter series, right? That first set of books that gives you a glimpse of worlds beyond, that whets your appetite and cultivates your imagination: the starter series sets the bar for every series that follows. Is it better? Is it worse? Does it have similar themes? Similar characters? Similar plots? Similar settings? Does it evoke that same sense of wonder, or a greater sense of wonder, or does it leave the acrid taste of disappointment in your mouth?

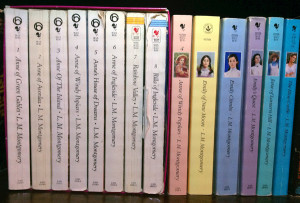

Cynicism taints almost every facet of my life. This may seem like an odd confession to make at the start of a literary influences post—especially one that focuses on the eternally optimistic works of L.M. Montgomery—but I feel like it has to be said. I acquired my cynicism by degrees from a pretty young age. By the sixth grade, I was a smart-mouthed, sarcastic, socially isolated 11-year-old. My only reliable friends were books (and with little wonder, given my temperament).

That was the year I met Anne of Green Gables.

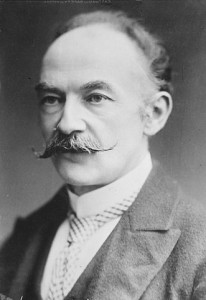

Heaven forbid that any of Thomas Hardy’s characters should ever get a paper cut; they’d probably saw off the injured limb in response.

I feel kind of odd listing him as one of my literary influences. He’s more my template of “what not to do,” which is terrible, because he’s generally considered to be a good writer, and many of his works are counted among the classics. I’ll set the stage for my dislike, shall I?