Continuing in our series of literary barrier objects, we delve into the boondoggle of excessive, expressive dialogue tags.

The Basics

A dialogue tag, as its name implies, marks who speaks a line of dialogue. It can be an attributive tag or an action tag.

- Attributive: “That’s nice,” Mary said.

- Action: “That’s nice.” Mary wiped her hands off on her shirt.

Both types indicate who spoke, but the action tag earns more points because it adds movement to the narrative.

This post deals primarily with attributive tags. That being said, beware the overuse of action tags, particularly if they involve a character turning, looking, staring, etc. Actions should pack a punch, not whiffle their rhetorical impotence against the air.

And thus we begin.

Excessive Dialogue Tags

When every line of dialogue gets a tag (action or attributive), those tags become barriers to the conversation. This form of tagging is great for first drafts, so that the author can keep track of character back-and-forth, but it needs paring in the editing phase.

Long story short: the author who informs their reader which character is speaking every single line demonstrates a lack of trust in their audience’s ability to follow a conversation. Don’t be that distrustful author.

(Although, admittedly, I’d much rather there were too many tags than too few. I haaaaate having to go back and count lines to figure out who’s talking.)

Expressive Dialogue Tags

I fought this one for years, y’all. Every writer has heard the adage, “Show, don’t tell.” Inevitably, expressive dialogue tags get paraded out as the prime violation to this guideline.

It’s the ongoing battle of the editors vs. the middle school English teachers. One says only to use “said” and “asked,” while the other gives out lists of alternatives and makes assignments for students to write whole stories without using “said” at all.

It’s not a matter of one being right and the other wrong. Tagging dialogue with a descriptive speech word instead of the blasé “said” or “asked” is a form of both show and tell, depending on which layer of language you’re looking at.

- On the semantic layer, you’re telling the reader how the character spoke.

- On the pragmatic layer, you’re showing the character’s mood through their manner of speech.

So why should semantics win out over pragmatics? It doesn’t always have to. Sometimes telling the speech style fits better in the flow of the story. (Show and tell should have balance anyway, or stories risk becoming overwrought.) But the battle between these two layers gets tipped, because there’s a third layer of language involved:

- On the syntax layer, you’re telling the reader who spoke any time you use a dialogue tag at all.

Attributive tags blatantly remind the reader that they are reading a book. The sole purpose of these tags is to clarify who says what, but if that information is already clear, they become redundant. (Yet another reason to use action tags more often.)

If you need to give attribution, the boring “said” and “asked” can easily fade into the narrative background, whereas more expressive tags mark this already-conspicuous construct further.

A Small Addition

In this category of “expressive dialogue tags,” we also include the “said + [adverb]” construct. In general, we use adverbs to prop up weak verbs. However, we use “said” specifically because it is weak, and thus largely invisible. If you’re changing “he snapped” to “he said angrily” for the sole purpose of eliminating expressive tags, you’re better off leaving it as “he snapped.”

(Although, admittedly, I love me some beautiful adverb usage, and I admire writers who toss them in without worrying about calling down the wrath of armchair editors everywhere. So.)

Excessive, Expressive Dialogue Tags

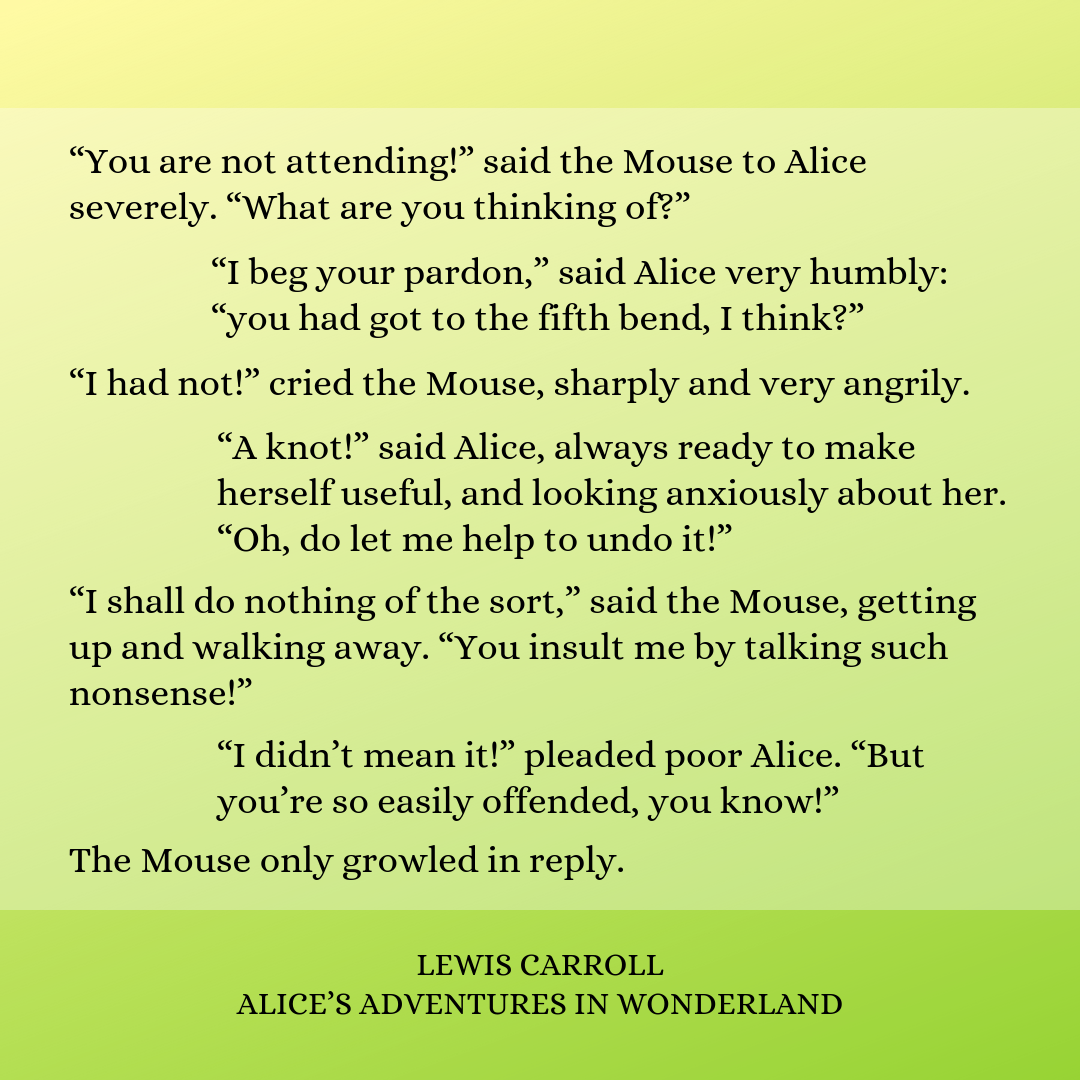

Our barrier object of excessive, expressive dialogue tags manifests when dialogue tags become so frequent and so flamboyant that they interrupt the story to call attention to themselves. Consider this passage from Chapter 3 of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865):

In this exchange between only two characters, every line of dialogue is tagged. We have said, cried, and pleaded, along with modifiers severely, humbly, sharply, and angrily. The excessive, expressive tags not only appear on every line, but they draw further attention through lack of pronoun use. (It’s always “Alice” or “the Mouse” speaking, never “she” or “it.”)

The barrier, then, becomes two-fold:

- The tags interrupt the spoken dialogue of each character, with sentence structure that blocks the flow of the full line of speech.

- That interruption in turn prevents narrative immersion, creating a block between the reader and the story.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the “I had not!” line of dialogue, whose subsequent tag might cause the reader to miss the joke in Alice’s response. “A knot? Oh, do let me help undo it!”

Carroll gets a pass because A) he’s writing in the mid-1800s and B) he’s writing for a young audience. Today this style of dialogue would be more prevalent in early-reader chapter books. It should reduce with Middle Grade and disappear from YA/Adult genres altogether.

A Good Barrier

Dialogue tags can gum up a conversation, but they can also act as pauses for when a character doesn’t rattle off their full line of dialogue in one go. Take this line from the excerpt above:

“A knot!” said Alice, always ready to make herself useful, and looking anxiously about her. “Oh, do let me help to undo it!”

The action of Alice searching for this supposed knot very nicely punctuates her first exclamation from her second. And while, had I been Carroll’s editor, I likely would have eliminated the “said” and made “looked” the main verb of the sentence (my above caveat against “looked” et al. notwithstanding), the placement of the tag in context really is lovely.

I’m also a fan of the occasional expressive attributive tag. They flavor a narrative when you can’t always shove an action into the mix, and they do it succinctly.

When used with care, dialogue tags of all types can become an asset rather than an obstacle.

However, One Final Caveat

With regards to expressive dialogue tags, beware mistaking action tags for attributive ones. You can’t shrug a line of dialogue. Or grin it. Or chuckle it. These and other similar tags are actions separate from speech. More specifically, they’re intransitive verbs, so they can’t structurally take a line of dialogue as their object.

(Because, as intransitives, they can’t take objects at all. Haha.)

/prescriptivism

***

Up next: Filter Verbs

Previous: Overuse of the Vocative Case

Back to Liar, Liar Navigation Page