Prescriptive Rule: “Never use a body part as the subject of your sentence.”

E.g., “Her shoulders rose in a hapless shrug.” (This structure is deemed bad, according to this rule.)

I randomly encountered this piece of advice a few months ago and was baffled because—confession—I break this “rule” all the time. When the adviser could yield no information as to why this would even be a thing, I went ahead and dug around the Internets a bit to find some reasoning. (You’re welcome.)

And I found three main points:

- It leads to dangling participles.

- It detracts from the character (agent) who is actually performing the action.

- It creates a sense of “autonomous” or “disembodied” body parts.

#1: It leads to dangling participles.

“While talking, her fingers curled around the warm, comforting coffee mug.” (Amazing, these talking fingers.)

Initial Assessment: I’ll give #1 a halfhearted nod for effort. Dangling participles are a legitimate structural issue, and for writers who view a featured body part as representative of the character, this trap might be too easy to spring. However, it’s not the body-part-as-subject’s fault. Dangling participles are sloppy writing and easily corrected:

- “While she was talking, her fingers curled around the warm coffee cup.”

In this example, the true subject reunites with its participle, and the fingers still get to curl. A prescriptivist might contend that a better fix would be,

- “While talking, she curled her fingers around the warm coffee cup.”

That, however, is a matter of debate. “She curled her fingers” is redundant, unless you want to argue that she could as easily be curling someone else’s fingers around the cup (which is 90% nonsense, 10% possible if this is a murder scene, the other person is unconscious, the coffee cup is the murder weapon, and “she” is framing “her”). The redundancy also makes it less efficient, especially since the writer can easily emphasize this character with the proper subject in the participial phrase.

Personally, I’d go with, “Her fingers curled around the warm coffee cup as she talked,” and skip the participle altogether.

Point #1 Diagnosis: The possibility of dangling participles doesn’t give license to forbid an entire class of subjects from someone’s writing. Rather than saying, “Never use body parts as subjects, because they can lead to dangling participles,” a better rule would be, “When using a body part as a subject, beware of possible dangling participles.” Or, more tongue-in-cheek, “When using a body part as a subject, your writing should have no dangling participles.”

(You see what I did there? Participles can dangle without body-part subjects, too. So let’s stop talking about dangling and body parts, shall we?)

#2: It detracts from the character (agent) who is actually performing the action.

“Roger’s elbow jammed into Sheryl’s ribcage.” vs. “Roger jammed his elbow into Sheryl’s ribcage.”

Initial Assessment: This point looks to sentence structure as well. In English, the beginning of any sentence carries a focus feature that inherently directs the reader or listener to where they should train their attention. If the subject is the first element we encounter, it draws that focus.

Theta-Roles

Syntax and semantics teach about theta-roles, particularly the Agent, Experiencer, and Theme. Because Point #2 is so concerned about the character getting displaced as an agent, this bears looking into.

- Roger’s elbow jammed into Sheryl’s ribcage.

- Roger jammed his elbow into Sheryl’s ribcage.

These two sentences have a distinct rhetorical difference. In the second, Roger intentionally jams his elbow. In the first, the elbow is jammed, but whether Roger did it intentionally depends on context. If, for example, Roger and Sheryl are tumbling down a staircase together, Roger probably doesn’t intend to jam his elbow into Sheryl’s ribcage. It happens due to gravity and physics and the chaos that results from two people colliding under those circumstances. Sentence #1 is, therefore, the correct description.

Even in the case where the elbow-jamming is intentional, however, sentence #1 has a good argument for use.

Say, for example, that Roger and Sheryl are listening to Peter rant about how someone spilled a can of paint all over his car. Roger knows that Sheryl did it. He jams his elbow into her ribcage to drive home the point. However, he does it surreptitiously, so that Peter won’t notice.

“Roger’s elbow jammed into Sheryl’s ribcage” carries both a narrower and a more removed sense to it. From Sheryl’s perspective, Roger is prodding her to speak, but he’s doing so in a secretive manner. Only the elbow moves. The narrowing of the agent from “Roger” to “Roger’s elbow” gives a minute rhetorical cue of this controlled gesture. Roger can still be fixed on Peter and his ranting while ribbing Sheryl.

Point #2 Diagnosis: Yes, using the body part instead of the person shifts the agent of the sentence. However, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Banning the structure all together is like telling all artists to get rid of their fan brush because some of their peers use it too much or improperly. It makes no sense, and it robs creators of a tool that could otherwise be used to good effect.

Better instruction would involve training in syntax and semantics, so that the author who starts a sentence with a body part does so wittingly, aware of its narrative effect.

(Education, what? Shock! Chagrin! /sarcasm)

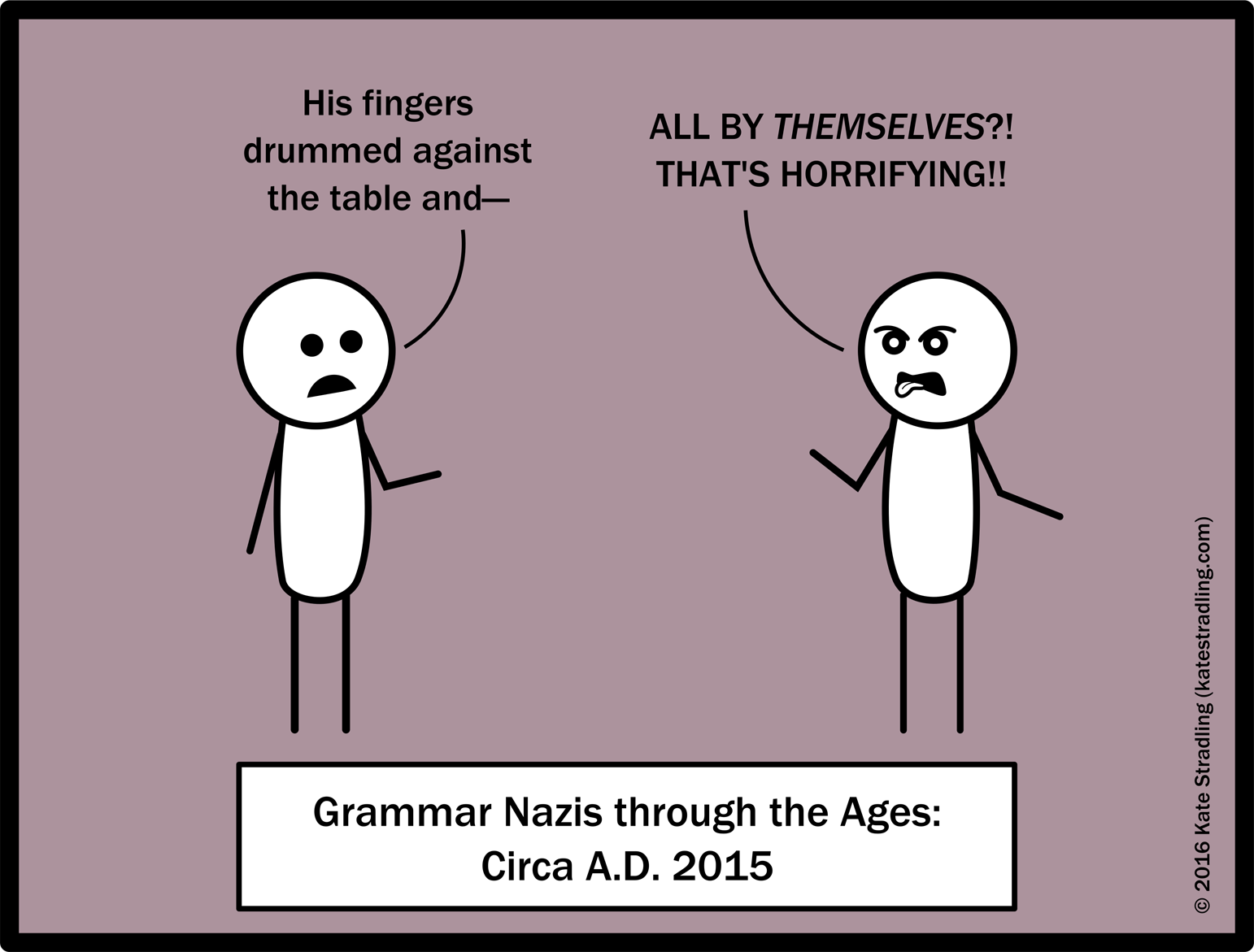

#3: It creates a sense of “autonomous” or “disembodied” body parts.

“Her shoulders rose in a hapless shrug.” (All by themselves, halfway across the room from where she stood. It was bizarre.)

Initial Assessment: “Ohmigosh! A disembodied hand just jumped into the narrative!” ~No reader, ever.

Pardon me for going off the rails here, but this excuse of “autonomous” or “disembodied” body parts is the MOST RIDICULOUS PIECE OF FREAKING GRAMMAR-NAZI DRIVEL THAT I HAVE EVER COME ACROSS IN THE WHOLE OF MY EXISTENCE. ARE YOU KIDDING ME??

- “Her shoulders rose in a hapless shrug.”

No reader in their right mind is going to take that sentence as indicating that a pair of shoulders unattached to a body somehow magically appeared on scene and are moving of their own accord. The same goes for the following:

- “His foot tapped a staccato rhythm against the floor.”

- “Her fingers danced across the piano keys.”

- “His eyes darted around the room.”

Body parts! Body parts everywhere!

EXCEPT NO.

See, there’s this thing about words. They have several layers of meaning built into them, layers beyond a simple dictionary definition. And when it comes to body parts, one of those layers dictates that the default condition for a body part is that it’s ATTACHED TO A BODY. That default remains in place unless specified otherwise.

So yeah, if you’re writing a zombie horror novel or graphic crime-scene thriller where disembodied parts are common and described in depth as being severed from their origin point, your reader might misunderstand a sentence that starts with a body part.

Might.

But probably not. Because readers aren’t stupid. (Or, at least, mine aren’t. *wink*)

Semantics—the layers of meaning that take in denotation, connotation, and sense for any given word and for the language as a whole—governs our understanding of language use. 99.9% of readers will never have that disembodied image enter their mind; the other 0.1% have heard this rule and had their mental process hijacked. (Thanks, prescriptivists!)

Or, worse, they’re being intentionally obtuse. “Look at this arm lurching across the page by itself, hur-de-hur-hurr!”

Point #3 Diagnosis: This is stupid. Quit using it as an excuse for telling people how to write.

The Eyes Have It

“Oh, but you should never have eyes darting, Kate. Eyes can’t dart, because they’re stuck in your head.”

Yes, exactly. They are stuck in your head, and everyone knows this. That’s why “darting eyes” works, actually. The minute the literal meaning comes up lacking, our brains switch over to a metaphorical one instead.

Don’t pretend you don’t know what darting eyes look like. I know you do.

A person’s eyes have long been synonymous with the scope of what they can see, but modern prescriptivists would have us believe that we should restrict the use of “eyes” in favor of “gaze.” And don’t even think about eyes doing anything beyond looking at other people.

I mean, unless you’re Shakespeare, that is.

Sonnet 137:

Thou blind fool, Love, what dost thou to mine eyes,

That they behold, and see not what they see?

They know what beauty is, see where it lies,

Yet what the best is take the worst to be.

If eyes, corrupt by over-partial looks,

Be anchor’d in the bay where all men ride,

Why of eyes’ falsehood hast thou forged hooks,

Whereto the judgment of my heart is tied?

Why should my heart think that a several plot,

Which my heart knows the wide world’s common place?

Or mine eyes, seeing this, say this is not,

To put fair truth upon so foul a face?

In things right true my heart and eyes have err’d,

And to this false plague are they now transferr’d.

William? Have you been ignoring prescritivist advice again, hmm? But surely that was a fluke, right?

Sonnet 5:

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell

Sonnet 14:

Mine eyes have drawn thy shape

Sonnet 78:

Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

Have added feathers to the learned’s wing

And given grace a double majesty.

Sonnet 121:

For why should others’ false adulterate eyes

Give salutation to my sportive blood?

But it’s only in the sonnets, right? He can take poetic license in a sonnet.

Haha.

All’s Well That Ends Well, Act V Scene 3:

KING. Now, pray you, let me see it; for mine eye,

While I was speaking, oft was fasten’d to’t.

and later,

LAFEU. Mine eyes smell onions; I shall weep anon.

Yep! Eyes playing tricks TWICE IN THE SAME SCENE! Now try this next one.

Antony and Cleopatra, Act III, Scene 10:

ENOBARBUS. That I beheld;

Mine eyes did sicken at the sight and could not

Endure a further view.

Shall I continue? If you go to The Complete Works of William Shakespeare over on Project Gutenberg, you’ll find hundreds of “eyes.” Shakespeare’s eyes draw, eat, smell, and speak. They are anchored and fastened. They sicken and stay and bend and turn. They are, in short, horrendously active in ways that their physical limitations might proscribe.

AND THAT’S OKAY.

Can “eyes” be overused in a text? Unequivocally, yes. But insofar as restrictions upon what task the eyes might or might not be capable of performing? CAN IT, GRAMMAR-BOTS.

You know what the author means when they reference someone’s eyes darting around the room. Quit straining at gnats.

/soapbox

Agreed!

So true! And yet, all I kept hearing, from the very start, was ‘The Adams Family’ theme song… my ears frequently drive me to distraction though.

Comments are closed.