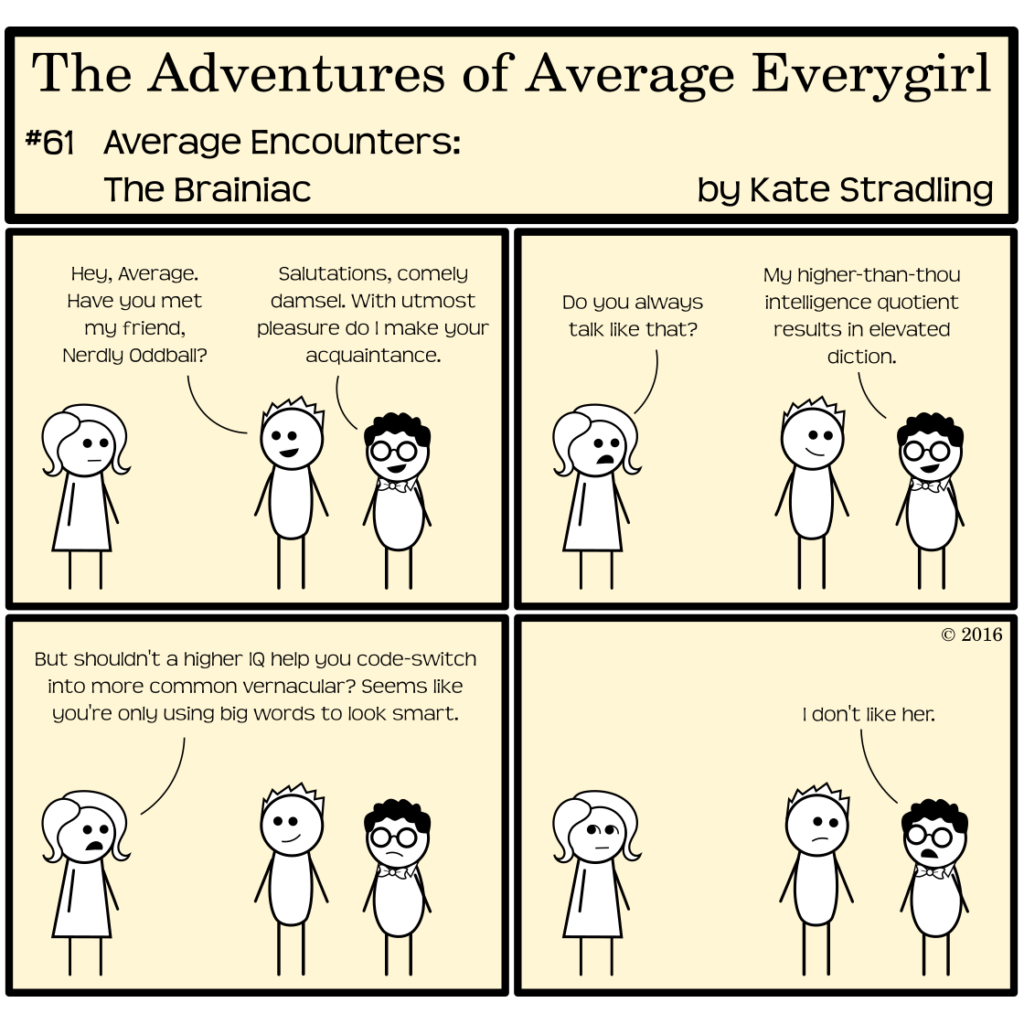

In the realms of fiction, the stereotypical nerd can be spotted from miles away: awkward, bookish, and almost always subpar in the physical department. They like to study, and they spout random factoids or scientific explanations.

They can be part of the group, but not really.

The Nerd in Society and Lit

Social narratives play a dangerous game when it comes to intelligence. We want to be smart, but not too smart. Innate genius is wonderful if it comes out of the blue, but it’s mock-worthy if a person decides to foster it above all other pursuits. “Normal” people can’t relate to “smart” people. The label, much revered and desired, can ostracize as easily as it endears.

The smart person lives in a different sphere, you see, and any attempt on their part to relate to the plebeian masses gets dismissed and/or ridiculed.

One of the most common tropes for establishing a character’s level of intelligence comes through dialogue: the smarter the character, the more $5 words they use. While this might seem intuitive at first glance, there’s much more to this pattern than meets the eye.

Nerd Speak: A Brief Linguistic Analysis

The linguistic field of Pragmatics teaches that language creates “Speech Acts”: that is, everything we say or write is meant to effect change. Language is not simply communication. It is manipulation. What we say and how we say it influence how others perceive us.

Thus, in a language that places high value on difficult vocabulary (i.e., English; thanks very much to the SATs for perpetuating this ideal), someone who uses a lot of big words receives the label of “smart.”

However, practical language use places a much higher value in being understood. On this scale, the smartest speaker would actually be the one who gets their point across unhindered by misunderstandings. In other words, a person who constantly has to explain or rephrase their speech isn’t really smart at all. They fail at communication.

(Unless their true desire is to communicate their superior knowledge of vocabulary, of course.)

A Speech in Three Acts

Pragmatics teaches of three different effects to every Speech Act: locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary.

- Locutionary Effect: The speaker’s actual words. E.g., A wife turns to her husband in the theater and says, “It’s so cold in here.” She is literally making an observation of the temperature of her immediate surroundings.

- Illocutionary Effect: The speaker’s unspoken intent. In the above example, the wife remarks to her husband about the cold because she wants him to do something about it: put his arm around her, give her his coat, commiserate with her, etc. No one simply observes the temperature of a room. At the very least, they want validation.

- Perlocutionary Effect: The listener’s reaction. The speaker has little to no control over this element. The husband of our example might put his arm around his wife, or tuck his jacket around her, or shiver beside her. He might just as easily say, “I’m fine,” or “I guess you should have brought a sweater.” And, chances are, his wife will be miffed, because the perlocutionary and illocutionary effects do not match.

Generally, as the speaker, we want the second and third effects to agree with one another. That is good communication. As the listener, though, it’s sometimes fun to flout the speaker’s expectations.

Like, really fun.

The bombastic speaker might intend the subconscious message, “See? Look how smart I am! You should stand in awe of me because I know so many big words!” but the listener can easily receive something along the lines of “I know more words than you! I’m so much smarter and special-er and different-er than you because I know big words! Hurr-de-hurr-hurr!”

Trigger the nerd-mocking.

Code-Switching to the Rescue!

For the record, I’m no enemy of elevated diction. (I mean, seriously, I just used the phrase “elevated diction.”) Certain situations require specialized vocabulary. Sometimes that $5 word is really the perfect descriptor. It all comes down to linguistic codes.

Everyone speaks in codes, both general and restricted. We use and encounter general codes out in the world: the combination of vocabulary, accent, and manner of speaking that best communicates meaning to the greatest number of people. For example, the nightly news aims for a general code, scripted to spread information to the public.

Restricted codes, as their name implies, occur in less popular settings and use a specialized vocabulary, accent, and/or manner of speaking. That silly voice you use with your brothers or sisters or children is a restricted code. Quoting film dialogue with friends is a restricted code. The jargon you speak with your work colleagues is a restricted code.

We have, each of us, dozens upon dozens of restricted codes, and the canny speaker instinctively knows which of these to use in any given situation, as well as whether to switch to a general code for better communication.

When someone fails to code-switch, then, they are sending a message, intended or otherwise: “I’m not like you. I’m different.”

And “different” is always a double-edged sword.

See, this is why I love visiting your blog! I always learn something new!

I’m so glad! Thank you!

Comments are closed.