In the 1960s and 70s, linguist H. Paul Grice defined the Cooperative Principle to explain dynamics of conversation. Even though his work hinges on real-life interactions, we will imprint it onto written dialogues.

The Cooperative Principle

If you’re not a linguist, the above quote is some lovely word salad. We’ll break down what it means in a minute, but first, some broader precepts.

If you’re not a linguist, the above quote is some lovely word salad. We’ll break down what it means in a minute, but first, some broader precepts.

Among its implications, the Cooperative Principle includes the following:

- Cooperation is our natural default.

- Implied meanings can be cooperative.

- Politeness is not required.

Cooperation: A Default Mindset

Grice holds that not only is the CP our natural default, but “that it is reasonable for us to follow, that we should not abandon” it (Grice, p. 48, and the emphasis is his, not mine).

We generally avoid conversations where we anticipate non-cooperation. This is why you might put off calling an insurance company, making a doctor’s appointment, talking to an ex, and so forth. If you suspect someone might give you grief rather than doing what you want, you delay engaging with them.

On the other side of the coin, we also avoid conversations where we personally don’t want to cooperate. Hence, we screen our phone calls, hang “No Solicitors” signs on our doors, and take the long way ’round to avoid someone tedious in the grocery store.

Cooperation is our default.

Implied Meanings

Under the Cooperative Principle, the listener has a responsibility to interpret the speaker’s intended communication, even if they have to ignore literal meanings. Analogies, sarcasm, double-entendres, and puns all fall into the realm of cooperation, even though the listener has to perform some mental legwork.

Thus cooperation, though a default, is more than straightforward communication.

Politeness as a Detriment

Not only is politeness not required for cooperation, but it can sometimes be a roadblock. Two people can have a shouting match and still be cooperative if each wants to communicate their frustrations to the other.

In contrast, someone who withholds an honest opinion for fear of offending is non-cooperative if their partner truly seeks their feedback. Politeness actually inhibits cooperation in that scenario.

However, if someone wants politeness from their conversational partner instead of the truth, bluntness becomes non-cooperative. There’s a bit of mind-reading involved.

Cooperation, then, occurs when both parties have their conversational expectations met.

4 Maxims of Cooperation

So how exactly does the Cooperative Principle break down? Grice identifies 4 categories that speakers must meet for cooperation:

- Quantity: Do not speak more or less information than necessary. No TMI. No skipping or withholding necessary details.

- Quality: Do not speak that which you know to be false or for which you lack evidence. No lying or gossiping.

- Manner: Speak in a clear, brief, orderly manner. No rambling, muttering, ambiguity, obfuscation, etc.

- Relevance: Speak only that which is relevant to the topic. No tangents.

(This is the simplified version, by the way. If you want more in-depth explanations, see his article reference at the end of this post.)

I’ve listed Relevance last because some pragmatists hold that it is the umbrella principle that everything else falls under. Lies and word vomit are not relevant to a topic, and speaking affectations draw away from intended meanings. Regardless, these four categories work together to produce solid communication.

The Cooperative Principle and Fiction

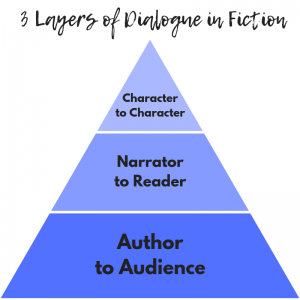

And all of this circles back to our 3 layers of dialogue. Why? Because “Good communication happens by keeping the Cooperative Principle, but interesting communication happens by breaking it.”†

And all of this circles back to our 3 layers of dialogue. Why? Because “Good communication happens by keeping the Cooperative Principle, but interesting communication happens by breaking it.”†

The only layer of dialogue that should always adhere to the Cooperative Principle is the Author to Audience layer. But remember, as an Author, you’re only being cooperative if you deceive your Audience.

In other words, your characters and your narrator should routinely break the Cooperative Principle.

Which is what we will explore next.

***

†This is either a quote or a paraphrase from my Pragmatics professor, Don L. F. Nilsen, whose name I had to dig through old boxes to find because it was well over a decade ago. But the sentiment has always stuck.

Reference:

Grice, H. P. (1975) “Logic and Conversation.” Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, Speech Acts, ed. by Peter Cole and Jerry L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press. Pp. 41-58.

***

Up next: Breaking the Cooperative Principle

Previous: Hedges and Qualifiers

Back to Liar, Liar Navigation Page