Whenever I see fanciful or imaginative place names, real or fictional, my first instinct is not, “Ooh, how neat!” It’s more along the lines of, “What were they smoking when they named that?”

I live in a city called Mesa. Literally “table,” because it sits on a plateau. Nearby land features include South Mountain (to the south), Red Mountain (guess what color!), and the Salt River, which runs through salt banks on the Fort Apache Reservation.

The Salt is fed by the Black and White Rivers, which come from the White Mountains to the north. (Where it snows. Surprise.) We also have the Verde River and the ever exotic Gila River (pronounced “hee-lah”), but don’t get too excited. They translate to “green” and “salty,” respectively.

The most imaginatively named land features in the area? Those would probably be Camelback Mountain, which looks roughly camel-shaped from the side, and a range to the east called the Superstitions. But these are, of course, part of that vast and intuitively named North American system, the Rocky Mountains.

(Spoiler alert: you can find many rocks therein.)

Place Names: A Fine Art

One might contend that this stark realism in naming is a feature of desert living, but it’s not. Place names across the world break down in a similar manner.

The British Isles sport a number of “feature” names that, thanks to language change, no longer appear as mundane as they once were. Consider the following elements:

- “dun” = hill

- “fen” = swamp

- “-more” = moor

- “-kirk” = church

- “avon” = river

- “-lea”/”-ly” = meadow

- “thorp”/”throp” = village

- “-ford” = river crossing

- “way” = road

- “strat” = street

When you start combining these with each other and with other elements, the resulting names have a classical, established sense to them. And then you realize that the River Avon is literally the River River, a “dunhill” is a hill-hill, and the high-sounding Fenmore can only denote an exceptionally boggy bog.

Even the poetic Stratford-upon-Avon breaks down into “street-river-crossing-upon-river.” And suddenly it’s not so poetic anymore.

This convention holds true for other languages as well. The infamous Llanfairpwllgwyngyll in Wales translates (reportedly) to “the parish of St. Mary in the hollow of the white hazel.”

Meanwhile, the New Zealand landmark of Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu might intimidate the casual reader, but it only means, “The summit where Tamatea, the man with the big knees, the slider, climber of mountains, the land-swallower who travelled about, played his nose flute to his loved one.” (Thanks, Wikipedia.)

Which is why, when I see fantasy book maps with mountain ranges called the Jagged Spine or the Teeth of Hecate or whatever, it rings false. From what I can tell, settlers across cultures have arrived in new areas, looked around, and said something along the lines of, “Hey, this forest is pretty black. Let’s call it the Black Forest.”

Semantic Bleaching at its Finest

Many place names carry an otherworldly, fanciful sense because their meaning is not readily accessible to the average speaker. Foreign wording or language change swathes the landmark in a layer of mystery. Places named for their founders or in honor of other notable figures further establish that esoteric feel, because more and more often, proper names exist separate from their original definitions.

This chasm between word and meaning introduces uniqueness and wonder, but it can also give the impression that place names are arbitrary.

Typically, they’re not.

Now, this isn’t to say that the run-of-the-mill fantasy author should put away their scrabble tiles and take a more conventional route to naming their landmarks. Rather, when the darts are thrown and the seemingly random letters assemble into a slick-sounding country, the questions that follow might be, “How came this name in the history of my world? What is its root? What does it mean?”

And the answer doesn’t need a lot of window dressing. In the end, there’s nothing wrong with a place called “Red River” or “Castle View.” On the contrary, that simple detail can lend authenticity in a world where the unfamiliar reigns.

My two cents. (Of course.)

I appreciate this so much! In South Carolina we have all kinds of crazy place names with odd histories. For instance, Honea Path was originally “Honey Path” – so named because the Indians went through that area to rob their bee trees. “Honey” became “Honea” because a clerk couldn’t read or spell, apparently, and it’s been Honea Path ever since.

Then there’s Walhalla, which given its mythological roots wouldn’t necessarily be weird except that it’s right in the heart of traditionally redneck territory. I’ll let you use your imagination to consider how that came about and how redneck Southerners might pronounce it.

My favorite is my hometown – Townville. It’s right down the road from Fair Play, and I guess after they named that one they had no creativity left.

“Townville” might take the cake. That is awesome.

I love that even fanciful names (like Honea/Honey Path) have a down-to-earth origin. Thanks for sharing your examples!

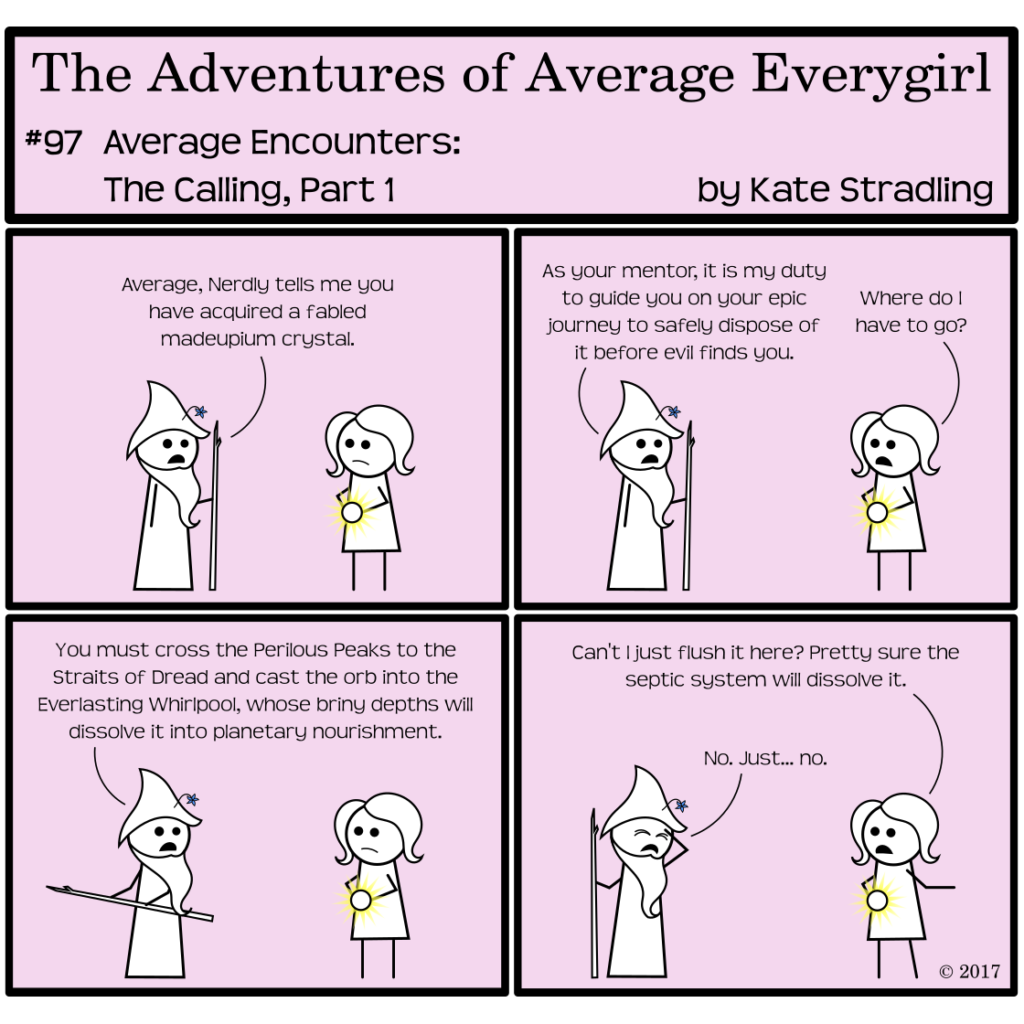

I love this! I discovered toponymy when I started naming places in my book, trying to figure out how to make them sound “real” and not contrived. (Straits of Dread and Everlasting Whirlpool are pretty awesome though 😉

Haha, thanks. I’m particularly attached to the Everlasting Whirlpool. 😀

Comments are closed.