Oh, the Interrogative Mood! What fun our questions bring to communication!

Here’s a quick run-down:

Direct Questions

Direct questions come in question/answer pairs, where the answer only fully makes sense in the context of the question asked.

Q. Who was the first president of the United States?

A. George Washington.

Q. Where are my shoes?

A. They’re under the table.

Q. How did you get here so fast?

A. I was already in the neighborhood.

None of these answers make conversational sense on their own. The person who randomly states, “George Washington” or “I was already in the neighborhood” is going to catch a lot of side-eye for it.

Also, the person asking these questions places their trust in the listener to give a truthful answer. The direct question always seeks truth (and thereby provides a nice avenue for the listener to mess with a gullible questioner, haha).

Indirect Questions

Indirect questions aren’t looking for verbal answers, necessarily. Or, if they are, it’s not the literal answer to the question asked. Indirect questions skirt around an issue. They pull politeness into the equation and communicate a need beyond their literal meaning.

Q. Have you seen Jane?

Translation: Tell me where Jane is, if you know.

Q. May I help you?

Translation: You look out of your element, and I am offering assistance.

Q. Can I please get by?

Translation: Move your ill-positioned carcass out of the way, roadblock.

This class of questions allows for conversational flouting, particularly if the audience decides to read them as direct questions instead:

Q. Have you seen Jane?

A. Yes. She’s a tall blonde with a snaggle-toothed grin.

Q. May I help you?

A. Looks kind of doubtful from where I’m standing.

Q. Can I please get by?

A. I don’t know. Can you?

Non-verbal responses can have the same dynamic of cooperation or flouting. For example, someone who asks “Can I please get by?” expects the other individual to move aside, with or without verbal acknowledgement; the second person might just as easily stand their ground in defiance or ignore the question entirely.

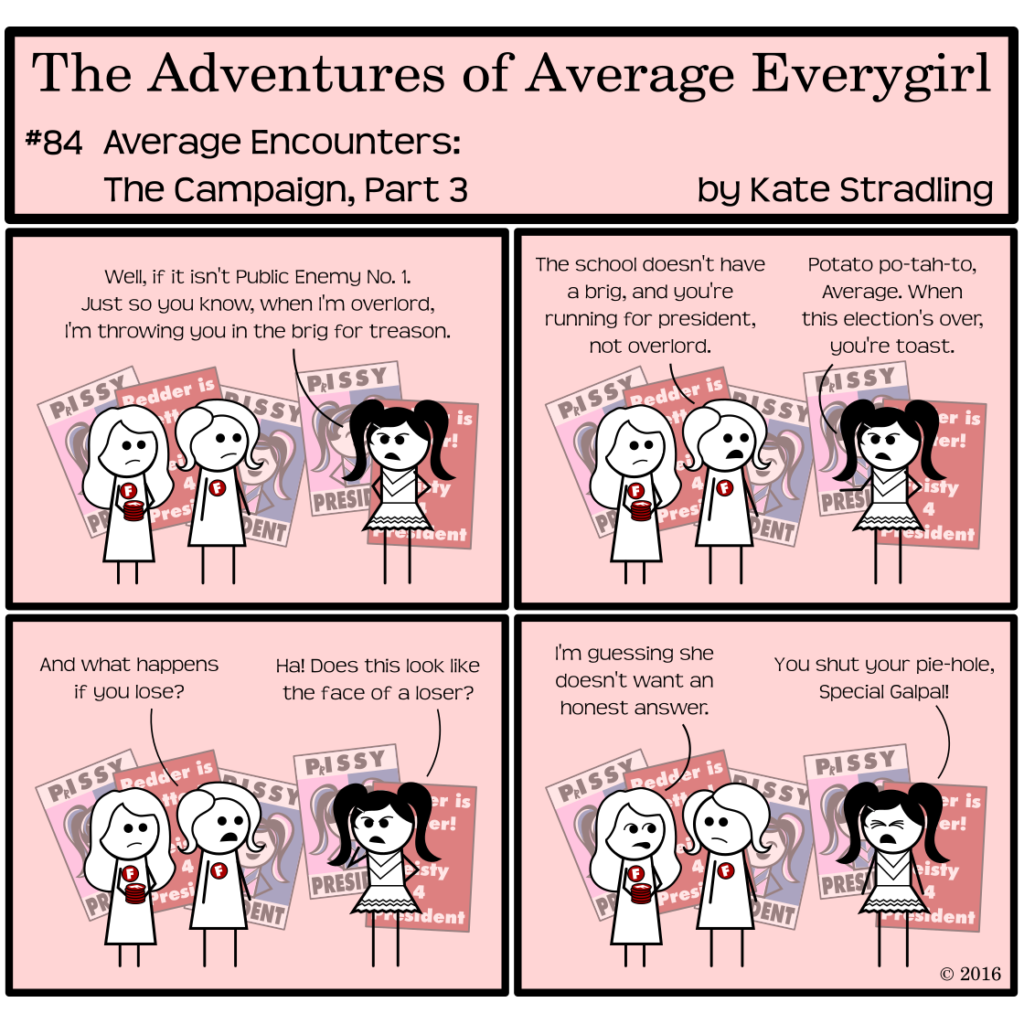

Rhetorical Questions

Rhetorical Questions aren’t looking for any answer at all. Rhetoric, as the art of persuasion, aims to shape the listener’s mind. The speaker isn’t seeking information, but imparting it. Thus, the question is designed to make its audience think, but not necessarily respond.

Q. Do you have any idea what time it is?

Rhetorical intent: Shame on you for losing track of time and/or causing me to worry.

Q. Does this look like a game to you?

Rhetorical intent: This is srs bsns. Wipe that grin off your face.

Q. Ain’t I a woman? (h/t Sojourner Truth)

Rhetorical intent: My life is just as valuable as any other woman—as any other human—on this planet.

The rhetorical question provides a means for drawing the listener into the same mindset as the speaker, but, like the indirect question, can also open the door for sass, particularly if the listener is at odds with the speaker. It also loses its oomph if the listener takes it literally and tries to answer.

Tag Questions

The tag question can seek either information or validation. It’s not freestanding, but appends to a declarative statement:

- You like strawberries, right?

- Paul can sing, can’t he?

- Mary wasn’t at the party, was she?

The answer to a tag question can be a simple yes or no, but it can also be an explanation of conditions. E.g., “I like strawberries fresh, but not freeze-dried.” “Paul hasn’t sung since high school.” “Mary came at the beginning, but she left after ten minutes.”

Tag questions in English are particularly fun. We can, like other languages, append a simple, “isn’t that so?” or “right?” or “correct?” to our statements, but the primary English tag-question structure involves a mirror opposite of the original statement.

Tag Formation

We form this structure by using a negative of the declarative auxiliary and a subject-matching pronoun (and, as with any Declarative-to-Interrogative transition, if there’s no auxiliary in the main sentence, “do” jumps in to take the role):

- You could come early → couldn’t you?

- Jim got home late → didn’t he?

- He’s not supposed to be here → is he?

The combo-breaker for this pattern is the first-person singular, when the auxiliary is “be” and the declarative is positive. Compare the two following examples:

- I’m not singing → am I?

- I’m singing → aren’t I?

“Oh, nope! I aren’t!”

Some people like to use “am I not?” as the tag question. And by “some people” I mean “stuffy people and sticklers.” The grammatically correct contraction would be amn’t, a’n’t—or, more colloquially, ain’t. But since we ran that term out of proper speech a century or two ago, we get aren’t as a fill-in.

Serves us right.

The negative stands on one side of the structure but not on the other, which cues the listener to give a confirmation or denial of the declarative statement. It also helps the speaker save face: rather than stating something which might be refuted and make them look uninformed, they invite the refutation from the outset, appearing open-minded instead.

Final Words

And an interesting social note: women are far more likely than men to use tag questions. Two possible explanations for this phenomenon are that we inherently desire more validation, or that we’re used to having our spoken statements challenged.

I won’t go into which I find more likely. It’s an interesting dynamic either way, don’t you think?

EDIT 2/23/18: A commenter has drawn it to my attention that the colloquial “women use tags more than men” assertion has dubious truth value, so I’m striking it from the article. Long story short, tag use is a whole lot more complex than it might appear at a glance.

But it does make a fascinating addition to the Interrogative Mood, doesn’t it?

(*wink*)

Some studies find men using more tag questions than women. Robin Lakoff’s work has been built on extensively since the “this is how men talk” vs. “this is how women talk” stage.

Mea culpa. Tags are a whole lot more complex than they appear. It seems the intent behind the tag question creates more of a divide on whether men or women will use it, and that men are actually more likely to express uncertainty of knowledge through tags, while women more often use them to facilitate conversation.

A fascinating construct, without a doubt. Thanks for sending me back into the literature!

Comments are closed.