In recent years, dystopia has experienced a surge in popularity. The readiness with which consumers gravitate towards stories of bleak futures, oppressive regimes, and outliers desperate to change the status quo reflects current economic, political, and social uncertainty. When dystopia is popular, the world itself is in upheaval.

A depressing thought, I’ll readily admit.

The term, which literally means “not-good-place” (from Greek), is an antonym for Utopia, a perfect society. Dystopias, then, present a negative future outcome, usually to an extreme degree.

Ironically, its supposed opposite wasn’t really all that better.

A Word on Utopia

The term “Utopia,” coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 tale of the same name, far from holding some wonderful meaning, is Greek for “no place.” More wrote in Latin (because anything of worth in those days was written in Latin), and he expected his reader to be well-enough educated to understand the translation for the place name, as well as for other proper nouns that appear within the work.

This was, primarily, because he wrote the piece with his tongue firmly planted in his cheek. The account of this perfect island society includes chamber pots made of gold and a visit from the Flatulentine ambassadors. In my copy, the elected officials’ titles are translated to “Sty-wards” and “Bench-eaters.” The Mayor of each town serves for life unless he tries to implement a dictatorship. (And why would he need to? He’s already got the position until he dies.)

Quizzically, the Utopian society includes elements we readily associate with our modern concept of a dystopia:

- Communism with a rigid social structure (no private property, and a set number of houses per city and people per house)

- Slavery (two per household)

- Euthanasia of the terminally ill (by choice, but after a lecture on how worthless their life is)

- Forced celibacy as punishment for immorality

- Public shaming (mainly of criminals)

- Prescribed careers (with a choice of wool-worker, stonemason, blacksmith, or carpenter, but everyone must take turns working the farmland)

Everything on the island is very orderly, and the people are very happy.

Kind of like the brainwashed denizens of modern dystopias.

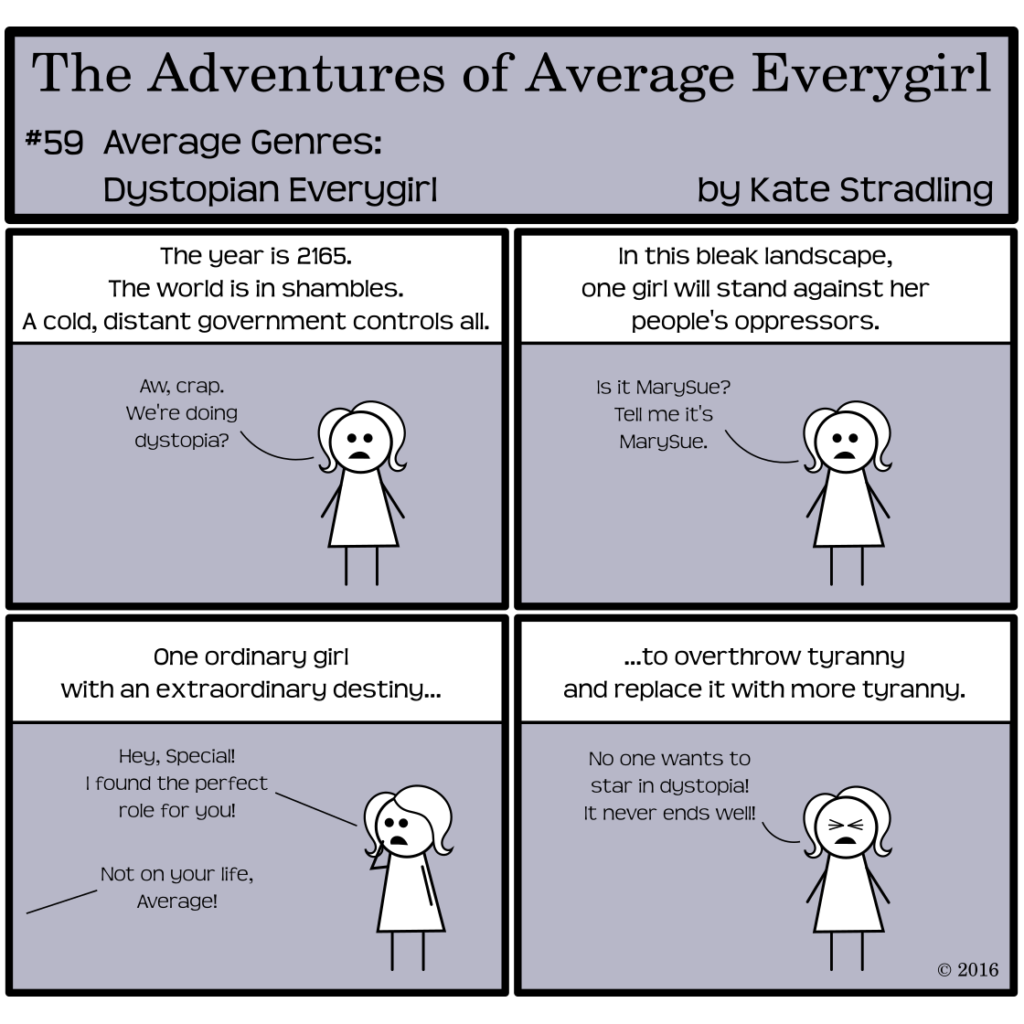

Dystopia Never Ends Well

The dystopian genre looks to a dismal future, and the flavor of dismal, in my opinion, is largely determined by one factor: technology.

Some classic examples:

- 1984 by George Orwell: Big Brother is watching you. Computer surveillance is everywhere.

- Brave New World by Aldus Huxley: Genetic engineering, clones, embryonic “hatcheries” instead of pregnancy, which is vulgar and disgraceful. Science has supplanted Mother Nature.

- Anthem by Ayn Rand: Hive-minded colonies stuck in a rebirth of the Dark Ages. Innovation is cause for punishment.

None of these books ends well. (You can argue that Anthem has a happy-ish ending, as the protagonist and his love interest escape to live free, but what’s their future look like, really? Two crazy kids, off in this abandoned house by themselves, determined to restore individuality when no one else seems to give a rip about it.)

More recent dystopias face similar issues. The ills of society are so huge, so overwhelming that they’re basically impossible for a protagonist to amend. In the cases where a successful revolution does occur, there’s no guarantee that its results will be any better than the original oppressive regime. Instead, the stories conclude on an uncertain note, at best a pause in the calamities of their chaotic world.

But that is dystopia by it’s very nature. You can’t escape. The governing destruction will always cycle around again.