The term “red herring” refers, in its literal sense, not to a living species of fish but to one that has been smoked, thereby rendering its tasty flesh a vibrant color. The smoking process also renders it distractingly stinky, which makes it perfect for training animals—or so the colloquial stories go.

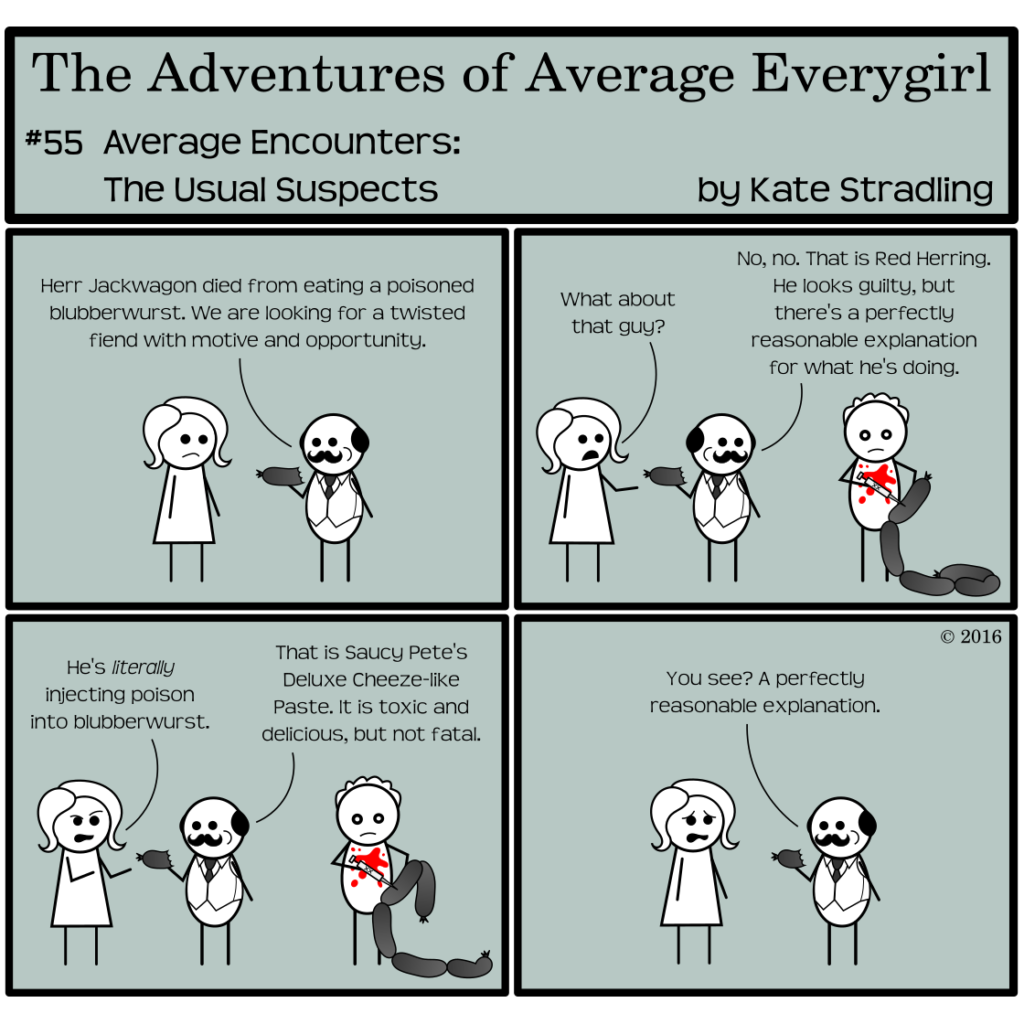

Figuratively, it’s a type of logical fallacy or literary trope used to draw attention away from another element. Because, you know, it’s red and stinky and stands out from the crowd while the element it masks is more bland and common. When you want the audience to look away from the Man Behind the Curtain, so to speak, you wave a red herring in their face. Or hide one in the air ducts so that the smell wafts into the room in a more subtle distraction.

Whatever works.

The mystery genre loves a good red herring. Really, every genre loves a good red herring. This goes back to the baseline premise that the reader comes to the story wanting to be fooled. The linguistic field of Pragmatics sometimes calls it the “garden path,” where the author (or speaker) carefully leads the reader (or listener) through a nicely arranged scene only to spring a trap upon them at the very end.

Because ultimately, literature, and particularly fiction, exists to effect emotional manipulation. The written word that does not create a transformative experience fails its purpose. This is true even of such mundane items as to-do lists. If you don’t act upon them in some way, there was no point in writing them in the first place.

But I digress.

Handle with Care

As a staple of the mystery genre, the Red Herring requires careful treatment. The reader expects a red herring, the reader is looking for it, and the reader will feel cheated if the herring turns out to be the culprit in the end after all, unless you really twist the knife to get there.

The trick, then, is to walk that razor’s edge of “Is he a red herring or isn’t he?” And sometimes, having multiple red herrings is the way to go.

“Is it this one? Or this one? Or this one?”

The best surprise is when it’s none of them, but only if the story supports the ending. Too often, mysteries lose their tension because the killer is obvious: a downplayed character mentioned early on and then omitted from the narrative while the amateur sleuth chases after outlandish red herrings. The “reveal” at the end discloses some withheld secret which, for the canny reader, produces an eye roll instead of any modicum of surprise.

Compare that paradigm to Agatha Christie (yes, again, because she’s brilliant), who places all the details systematically before her reader. She keeps all her likely suspects in play and springs her trap at the end of the novel with a reveal that pieces all of those seemingly disconnected details together in one fell swoop. The reader, far from any eye-rolling or indignation, is left thumbing back through the pages going, “No! That wasn’t there! Yes, it was! What?!”

(Or maybe that’s just me.)

A Red Herring in the End

Christie’s opus is more than entertainment for the masses or study material for mystery writers alone. All stories, in one way or another, are mysteries, unraveled line by line upon the page. A study of her methodology, then, can bring new understanding to the story-telling process itself.

That genre label on her books, Mystery? Surprise! It’s only a red herring in the end.