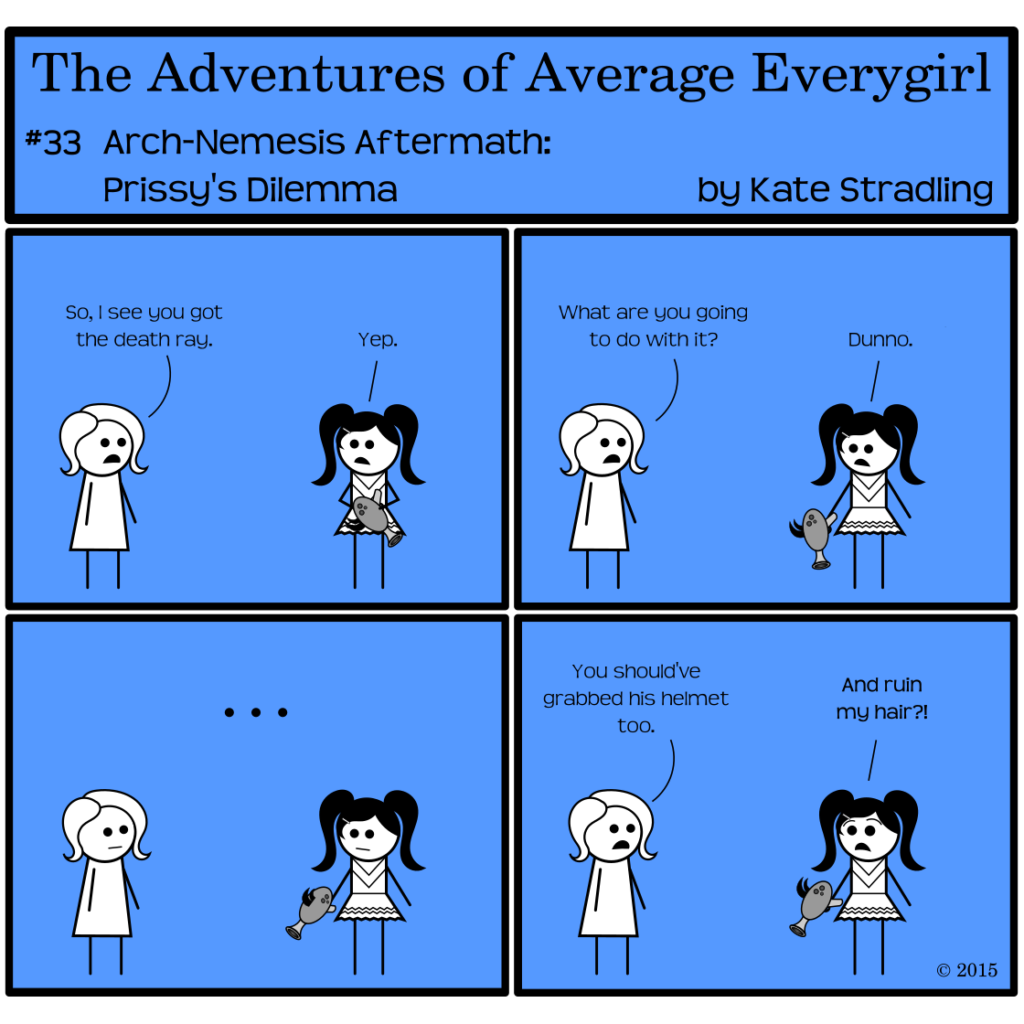

I’ll admit it. I tried the helmet on Prissy. It would have required me to alter her bangs, and that cute little barrette would have had nowhere to go. Barrettes under helmets are painful, and I couldn’t see Prissy casting hers aside. Villains, like protagonists, need to have their priorities, after all.

First things first

Priorities determine a villain’s objectives, their motivation to achieve those objectives, and how much time they dedicate to the whole endeavor. A villain who prizes puppies above all else will stop in the middle of a murderous rampage to pet one, or at least agonize over the decision. (And, presumably, will be the villain of a slapstick.) Likewise, a villain who prizes power will stop at nothing to gain it.

The cliché Villain’s Exposition speech sometimes contradicts a villain’s presumed priorities. For example, how many times has James Bond been in the clutches of his arch-nemesis, only to have that arch-nemesis pause and expound upon his grand dream of destruction and control instead of just blowing Bond to bits? That’s not a villain who truly craves power. That’s a villain who craves validation.

“You see, Mr. Bond? I’m so insecure that I must have your reaction to my diabolical plans before I kill you, so that I may savor your shock and defeat all the more during those long, cold nights when I’m all alone. Only my cat loves me. And only because I feed him.”

But then, the villain simply pulling the trigger (or lever, or switching, or whatever mechanism will bring about death and mayhem) doesn’t draw out the suspense. Will Bond escape? How will he outsmart the bloviating bad guy?

Just kidding. No one goes to Bond for suspense. They go to him for action and fighting and explosions and babes and manly grunts. So it doesn’t matter that he keeps running up against insecure would-be despots who mask their insecurity with a supposed thirst for power or revenge. The Bond villain is simply part of the Bond formula. His priorities are pretty messed up, but that’s human nature for you.

Priorities as a Pattern

In real life, there are always two sets of priorities: the What I Say and the What I Do. Rarely do these two sets match up, because humans are fractured creatures. Applying this duality to fictional characters brings an interesting dimension of reality to a story. It can either kick the reader out or draw them further in.

“Why did she do that?” The answer to this question must be something better than, “Because that’s how the story gets from A to B.” Everything a well-rounded character does ties back to who that character is as a person. If it doesn’t, the character’s not well rounded, and the canny reader, accustomed to interacting with well-rounded people in real life, will be able to tell the difference.

This applies to protagonists, antagonists, window characters, and the rest of the character spectrum.

Exhausting to consider in its full scope? Yes, absolutely.

Should writers make it a priority in their craft?

(I’m sure you can guess my answer to that.)