The first barrier object on our list, 3rd Observational Point of View, falls into the domain of rhetorical structure. As discussed in an earlier post, Point of View strongly influences the relationship between the Narrator and the Reader. And, when used unwisely, it can gum up that relationship as easily as it can promote it.

POV Overview

The standard 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person points of view receive their designations according to which pronouns the narrator predominately uses, and they act as the camera lens through which the reader receives the story.

So, 1st Person POV (I, me, my, we, us, our) gets restricted to anything the narrator can see, hear, feel, etc. Events where the narrator is not present or conscious require summarizing after the fact or else a switch in POV.

2nd Person POV (you, your) is the devil in fiction. It’s been done, but it’s a fussy lot of work unless you’re writing a Choose Your Own Adventure. In which case, fire away.

3rd Person POV (he/she, him/her, his/her, they, them, their) has a broader scope in what it can show, from a panoramic sweep of a battle scene to an up-close-and-intimate conversation.

Within each of these categories lies sub-categories of style. For example, the default 1st Person POV uses past tense, with the narrator telling a story after the fact. In contrast, 1st Person Present POV (aka Lyric 1st Person) uses a simple present tense, which can feel awkward for readers unaccustomed to its style.

(We don’t use a lot of simple present in our real-life storytelling. The stylistic choice to use it in a novel places the reader directly in the action as it happens. It also places on the author an onus to be consistent.)

Presumably, 2nd Person POV would have similar divisions between past and present tenses.

But the real fun lies in the 3rd Person categories.

Sub-Divisions of 3rd Person

In 3rd Person, point of view divides its styles into the Three Os:

- Omniscient

- Objective

- Observational

The Omniscient narrator, as the name implies, knows everything. A specialized type of this sub-category, the Limited Omniscient narrator, knows everything about their focal character(s): thoughts, opinions, assumptions, etc. Another specialized type, Free Indirect Style (as pioneered in Jane Austen’s Emma) actually shares those thoughts, opinions, etc. Everything is fair game with an Omniscient POV style.

The Objective narrator knows only what they can see. This style, most notably employed by Ernest Hemingway (see “Hills Like White Elephants” for the typical high school English example), has a sparse, stark narrative that leaves the reader to interpret much of what is going on. There’s no insight into character’s thoughts or opinions beyond what they express aloud.

Like the Omniscient narrator, the Observational narrator knows pretty much everything. The difference? They like to editorialize on it. Sometimes frequently.

And that’s exactly how they become a barrier.

3rd Observational Point of View

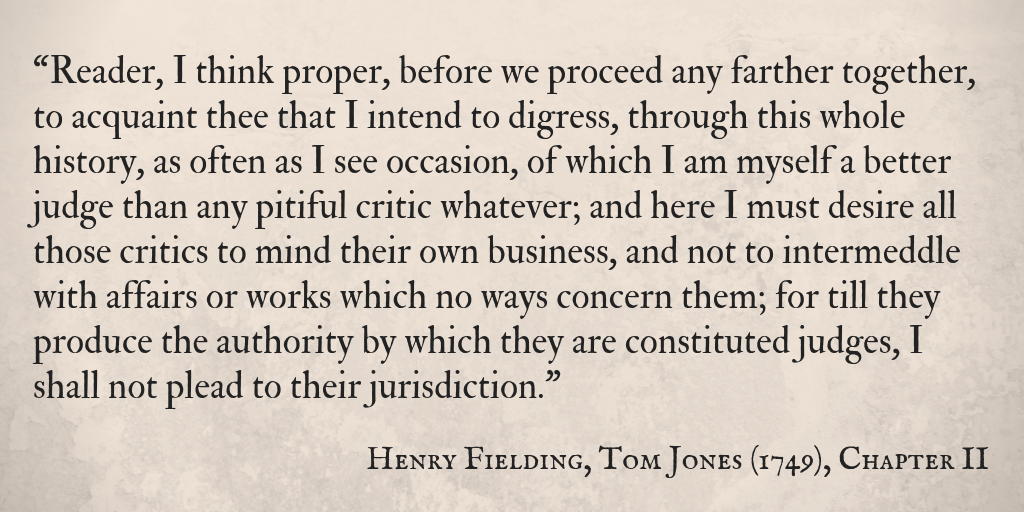

Consider the following paragraph, from Henry Fielding’s masterpiece, Tom Jones.

(Tl;dr, “I’m going to go off on tangents whenever I please, and critics can shove it, because they’re not the boss of me.” I might need this embroidered and hung above my writing desk. But I digress.)

Now, this narrator is using first-person pronouns all over the place. Quizzically, this does not a 1st person narrator make. Tom Jones is told in 3rd person, with these momentary asides where the narrator steps into the frame and expostulates.

Because that’s what the 3rd Observational narrator does.

Exception to the Rule

As far as I’m concerned, Henry Fielding is the master of 3rd Observational POV. He owns the trophy. The rest of us can go home.

But he’s also a product of his time, writing in the mid-1700s when the novel was still a fairly new medium. Early English novelists had issues with treading the boundaries between fact and fiction. Precursors like Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver’s Travels were published as though they were accurate accounts (e.g., Gulliver’s Travels originally credited Lemuel Gulliver as its author, not Jonathan Swift). Samuel Richardson, in his preface to Pamela (1740), claims the title of Editor instead of Author, and ascribes the letters to truth and nature.

Liars, all of them.

Fielding, too, treads that line between truth and fantasy. He treats his characters as though they once lived or yet still do. At one point in the book, he even casts his own brother in a role. He is very much both Author and Narrator at the same time, but he differs from his predecessors (Richardson in particular) in that he never shies from claiming his story as a work of fiction.

Instead, Tom Jones becomes an instructional between Author and Audience, in which Fielding basically trains his readers on how to consume the story he will unfold.

Which, again, was fine for the 1700s. The modern reader, in contrast, is already trained.

The 3rd Observational Barrier Object

3rd Observational Point of View rears its head in such folksy phrases as, “Dear Reader,” “Our scene opens upon…” and “We now turn our attention to…” This narrator directly addresses their reader outside the events of the narration, sort of a chummy, “Hey, buddy-buddy-buddy” literary elbowing that almost screams, “PLEASE LIKE ME! WE’RE FRIENDS, AREN’T WE?!”

Rhetorically, this style interrupts the flow of the plot in favor of the narrator trying to establish some rapport with their reader. And it can show up in seemingly innocent ways, including such narrative commentary as:

- to be honest

- honestly

- naturally

- in fact

- actually

- indeed

- of course

All of which are largely superfluous in narration.

At its best, this style conveys satire and tongue-in-cheek good humor. At its worst, though, it becomes condescending, a narrator who goes out of their way to explain their every impression as the events of the story unfold. Because their reader is obviously incapable of interpreting such things on their own, right?

A narrator, in short, that drives readers away instead of inviting them in.

Unless you’re using this style on purpose, with a clear understanding of the effect you intend to cause, it’s probably best to ditch this barrier in favor of more efficient narrative methods.

***

Up next: Overuse of the Vocative Case

Previous: Barrier Objects: An Introduction

Back to Liar, Liar Navigation Page

Question: What would it be considered if the character narrates himself in third person? He isn’t the primary narrator, so in his sections things take a step back and he tells his observations to the reader. Would that count as Observational Third or is it a wacky first?

Oh, gosh. Of the two, my vote is for “wacky first.” To my understanding, Observational Third comes from a narrator who doesn’t play an active part in the events of the story. They only recount them with added commentary, like a storyteller who frequently addresses an audience to keep them engaged.

Characters who narrate themselves in the third person, though, are probably going to have a more whimsical (and yes, wacky) feel to their narration, just like when people do the same in real life. It might fall into the Limited Omniscient category, since they’ll know and share their own thoughts or feelings. Or, you might be experimenting with something new. I can’t think of any extended examples for this style off the top of my head, but I’m 100% intrigued!

Thanks. I was writing my NaNo novel and realized that I’d written the love interest’s perspective in third person, but the MC in first. Your posts really get me thinking about my writing, so I figured I’d ask.

It sounds like your MC’s love interest might have a separate narrator rather than narrating him/herself in 3rd person.

I have seen books that switch between 1st and 3rd Limited Omniscient. Most notable to my memory is The Bartimaeus Trilogy by Jonathan Stroud, where the eponymous genie narrates his own chapters, but a 3rd Person narrator steps in for the chapters that center on first Nathaniel and then Kitty. A lot of it depends on how deep the author wants to go into a character’s psyche (or, alternatively, how deep they want their audience to go). 3rd Person is, by its nature, a degree removed. So, the switch allows for greater sympathy/focus on the 1st Person character.

Long story short, it makes perfect sense for the MC to have a deeper, closer POV and for the narrative to pull back when it switches to someone else. We generally want our audience to relate best to our MC, and using 1st person for them alone is a subtle way to reinforce that.

Good luck with NaNoWriMo! 🙂

Comments are closed.