The Epistolary Style is a narrative technique wherein the story progresses via letters, journal entries, newspaper articles, or other written forms of communication.

A novel may be epistolary in whole or in part.

Truth in Form

This style creates an inborn feeling of authenticity. Some of the earliest English Novels were epistolary, with an implication that they were genuine correspondences rather than works of fiction. For example,

- ROBINSON CRUSOE (1719) originally listed its eponymous protagonist as its author instead of Daniel Defoe. This led to speculation that it was a true account, not just a story.

- GULLIVER’S TRAVELS (1726) attributed Lemuel Gulliver as its author when first published, and the 1735 edition added a letter from him declaiming unauthorized edits in the first edition. Granted, Jonathan Swift was more shielding himself from criticism and/or prosecution for his story’s deep satire and political messaging. The Epistolary Style gave him an excellent hiding place.

- In his preface to PAMELA (1740), Samuel Richardson claimed the letters were real and that he was merely their editor. This novel, a cultural sensation, was preached from church pulpits as an example of virtuous conduct.

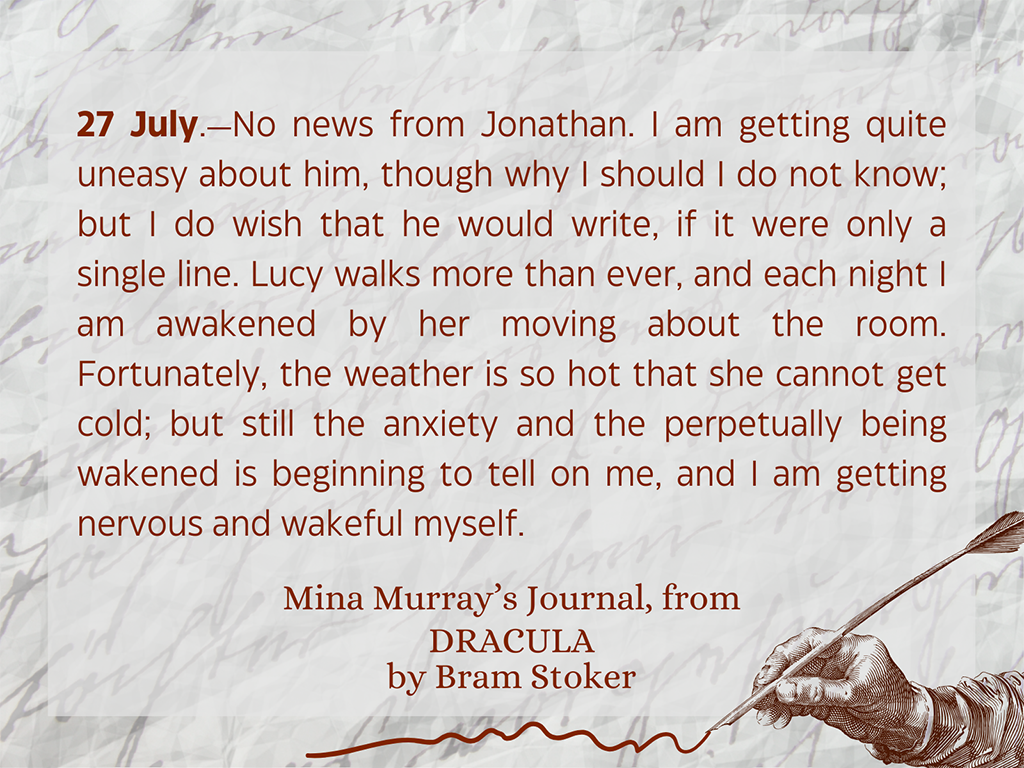

Inborn Intimacy

The Epistolary Style establishes a close rapport between the Reader and the Journalist Character. It plays up the secretive intimacy of accessing someone else’s private papers, of being privy to their inner thoughts. And it does so without any modicum of guilt.

Most of us would never steal and read a stranger’s correspondences. Or, if we did, we’d experience at least a twinge of conscience, because this represents a significant invasion of privacy. When the “stranger” is a fictional character, though, they become instead a friend, and the Reader becomes their trusted confidante.

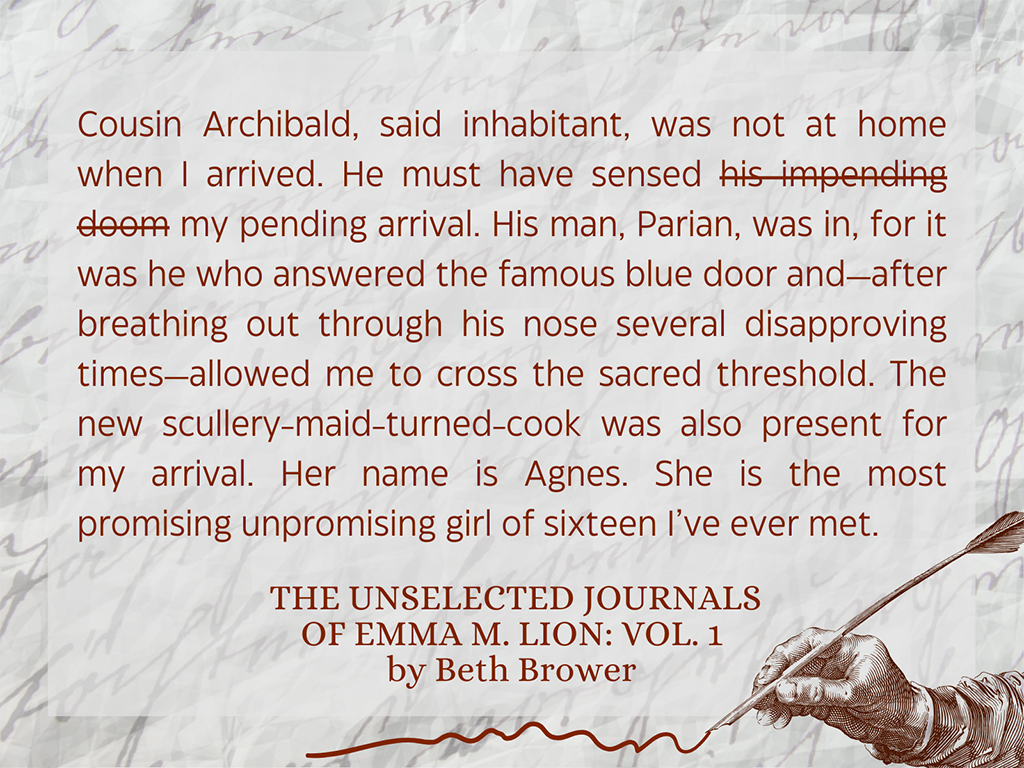

Editorial Freedom

On the Author’s side, the Epistolary Style allows for easy editorializing of story events. What better place for honest or irreverent commentary than a personal diary or a letter to a close friend? The Journalist Character can be candid or snarky but still endearing.

Thus, the epistolary novel allows its Author to showcase both Characterization and Tone.

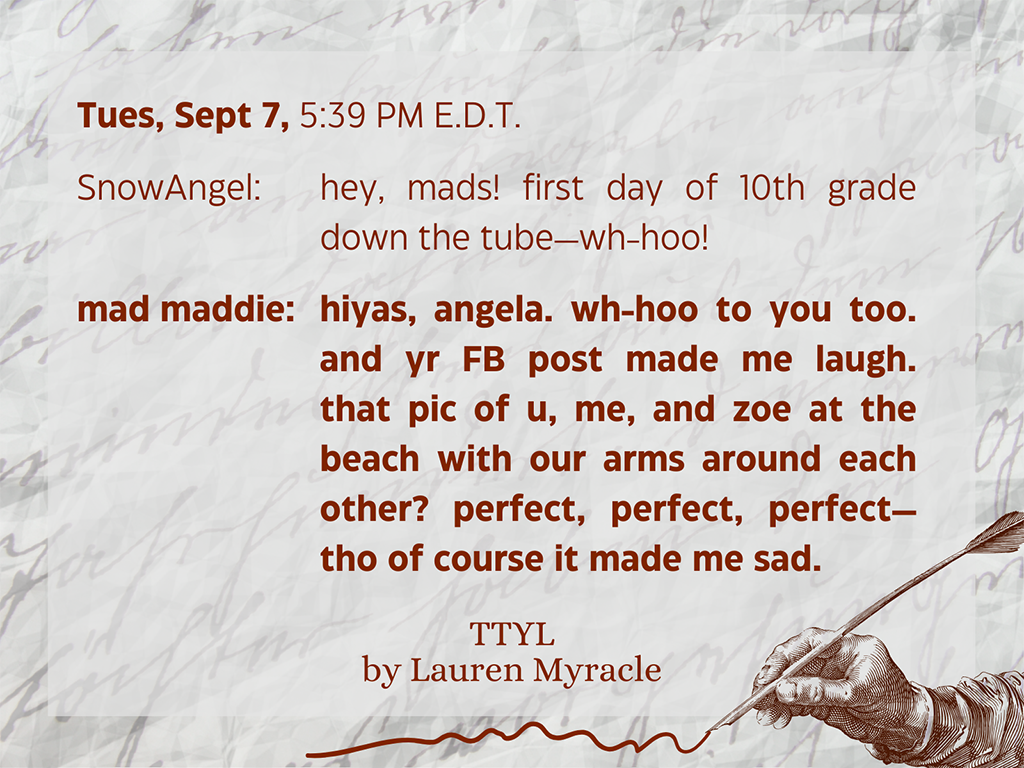

Ever Evolving, with Boundaries

While this is one of fiction’s oldest styles, it’s also a timeless one. The diaries and letters that created yesteryear’s epistolary novels have expanded to include text exchanges and social media posts. Whatever written medium humans might use to communicate, novelists can collect it under the Epistolary umbrella.

But, of course, it has its limitations.

A purely epistolary novel limits the scope of the story in much the same way as Limited Omniscient Narration. The Journalist Character(s) can only record their own thoughts, opinions, and experiences. Anything that happens outside their field of knowledge cannot grace the page.

For those choosing the Epistolary Style, beware the inclination to info-dump pages of exposition. Also, remember to temper character musings with Conflicts that push the Plot forward. Extended bouts of introspection can become tedious to read.

Most importantly, have fun. This is a style of many variations and narrative opportunities.

- What is your favorite epistolary novel?

- How might this style benefit a story? How might it detract?

Up next: Stream of Consciousness

Previous: The Panoramic Method

Index Page: Point of View

Would this style of narration also include works that are told as if the Narrator is retelling the story to the Reader from a previous source, even if the style is not written directly in letter format? Or does that fall under a different category? I’m thinking primarily of The Chronicles of Narnia — here’s an example from “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: “It brought both a smell and a sound, a musical sound. Edmund and Eustace could never talk about it afterwards. Lucy could only say, ‘It would break your heart.’ ‘Why,’ said I, ‘was it so sad?’ ‘Sad!! No,’ said Lucy.”

No. The narrator-retelling-a-story would fall under Observational Narration. That’s where I’d put The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, whose narrator’s opinions are evident from the iconic first sentence: “There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” The excerpt in your example is a moment where that Observational narrator steps into frame.

Epistolary Style can be Observational (and often is), but it requires that extra layer of “written word” format, where the Reader understands that they’re reading a letter, diary, news article, etc.

Thank you!

You’re welcome!

Comments are closed.