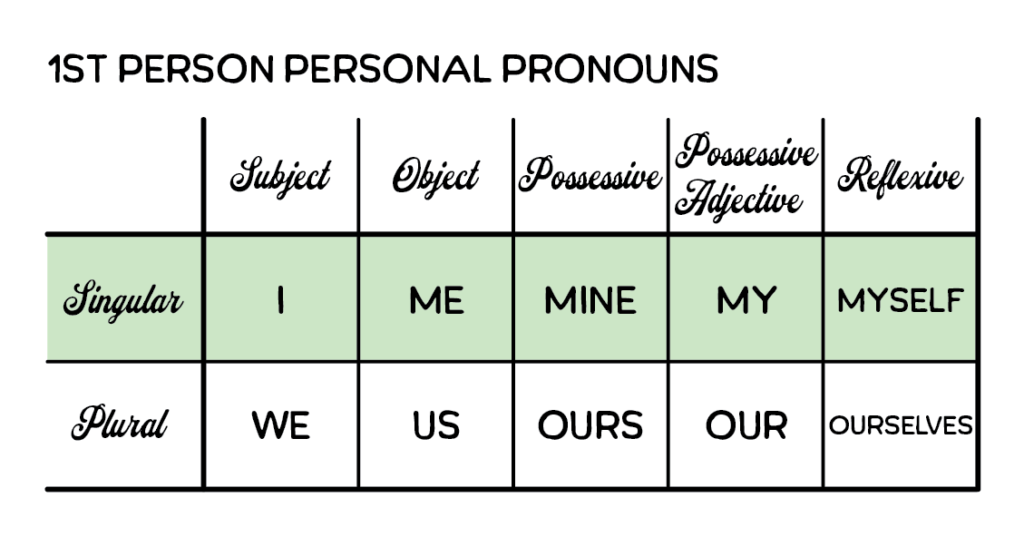

In First Person Point of View, the Narrator is a character who exists within the story world. They use first person personal pronouns to describe their experiences and encounters with other characters, the setting, and the plot.

That’s it. That’s the only requirement.

This Point of View is common in Young Adult and genre fiction, and—for obvious reasons—memoirs and creative non-fiction. It’s also surprisingly popular in contemporary literary fiction.

And although the definition for First Person is straightforward, it invites a multitude of variations.

Singular vs. Plural Pronouns

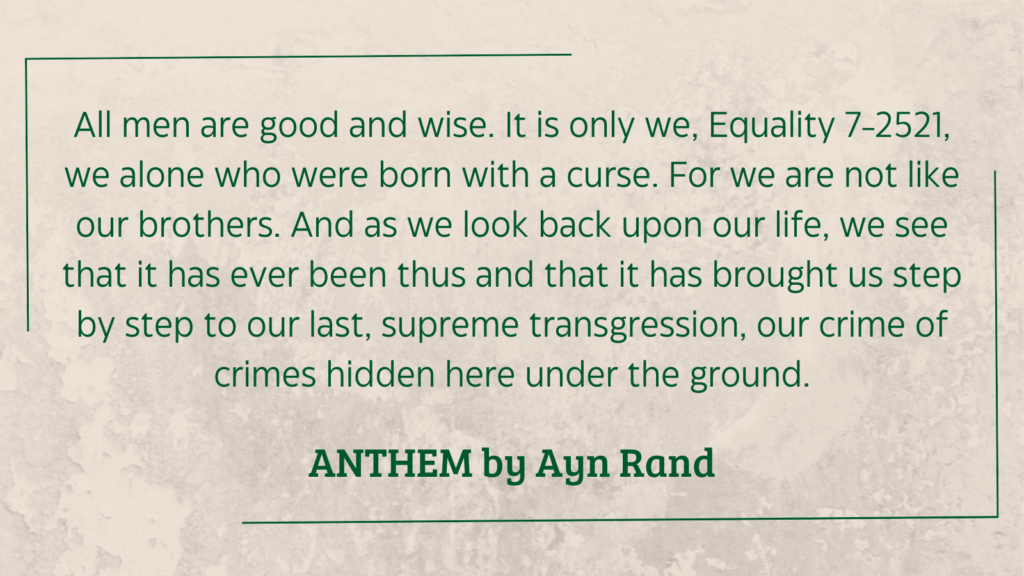

Most narrators will use singular pronouns by default. It’s not required, though. In Ayn Rand’s ANTHEM, the single narrator uses plural pronouns, an element which aligns with the dystopian setting and themes of the book.

A use of plural pronouns instead of singular can indicate a society without individualism, or it could indicate a collective narrator instead of an individual. It’s certainly a fun variable to play with.

Internal vs. External Audience

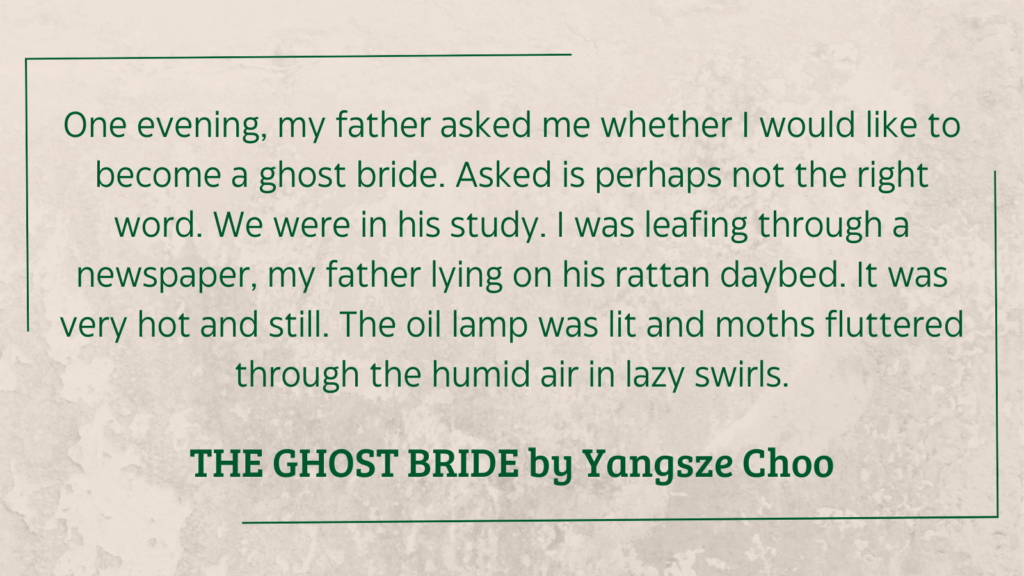

First Person narrators can also address either an in-book or out-of-book audience. In THE GHOST BRIDE by Yangsze Choo, the narrator, Li Lan, tells her fantastic tale to an external audience, bringing her Reader along for her adventures into the afterlife.

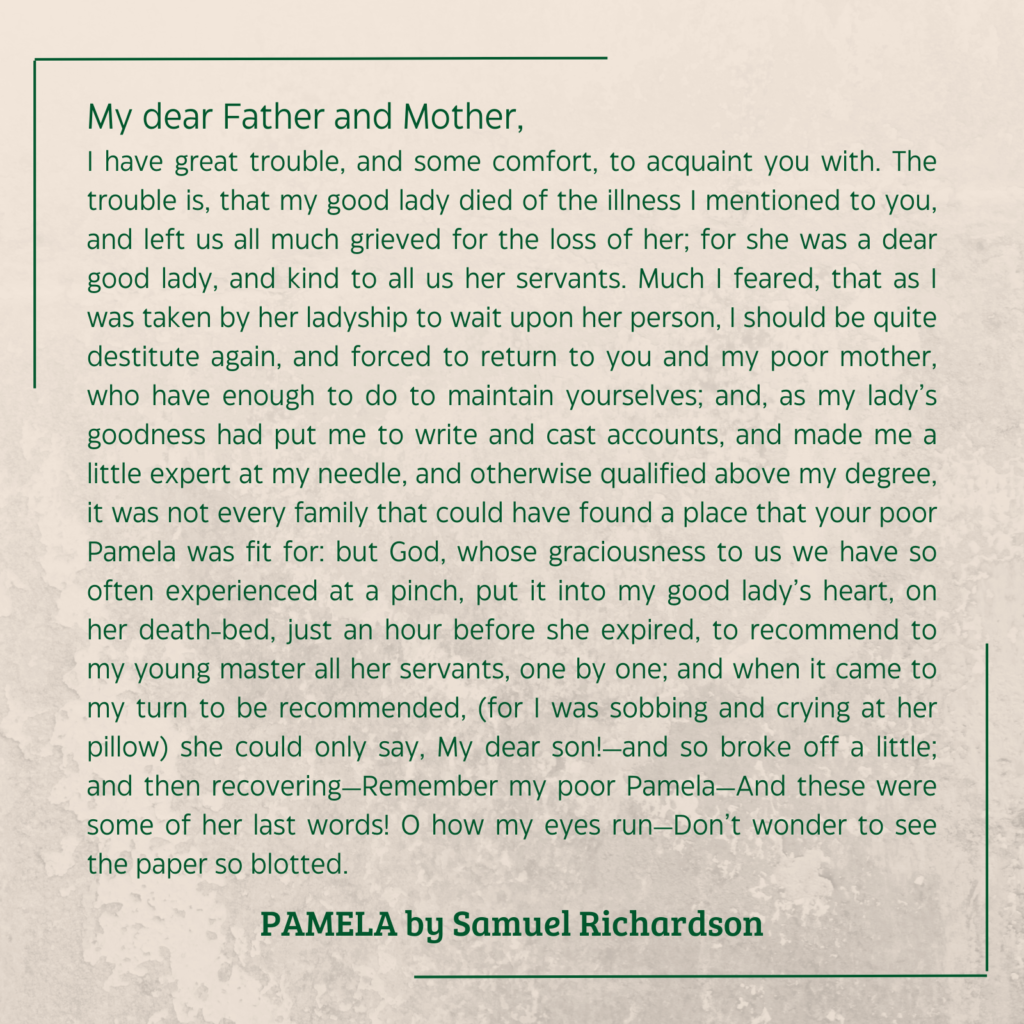

Compare that to the internal audience of PAMELA by Samuel Richardson, where the eponymous heroine writes her stories in a series of letters addressed to her parents.

Oh, the irony of Pamela’s mistress pleading thus with her son, who happily remembers poor Pamela as someone he wants to prey upon. The external audience knows Pamela’s in for a wild time, while the internal one—and Pamela herself—remains ignorant to the calamity that awaits.

When a first person narrator addresses an in-book audience, it creates a sense of secrecy and gossip: the Reader has stumbled upon someone’s private papers and has access to their innermost thoughts.

The epistolary style need not have an internal audience, however. ROBINSON CRUSOE by Daniel Defoe features a first person narrator addressing an out-of-book audience as he recounts his adventures.

Internal Monologues & Self-reflection

First Person POV creates an easy mechanism for internal monologuing and self-reflection. In THE MELANCHOLY OF HARUHI SUZUMIYA by Nagaru Tanigawa, for example, the narrator often expresses his gut reactions within the narration in lieu of saying them out loud.

The effect is comical, a very put-upon young man venting his frustration while he endures the bizarre events of his story world. His combination of sass and self-restraint endears him to the Reader.

After all, most people have things they think but do not say aloud. By providing access to an internal monologue, First Person Point of View allows your narrator to express their thoughts without the drama of lashing out at their fellow characters.

Omissions & Ambiguity

Because everything funnels through the narrator’s perception, this POV allows the author to obscure details through omission and/or ambiguity.

A classic example lies in withholding the narrator’s identity for either comic or dramatic purposes. Again in THE MELANCHOLY OF HARUHI SUZUMIYA, the Reader never learns the name of the narrator, only that people call him Kyon and he hates it.

Similarly, the narrator of REBECCA by Daphne du Maurier never reveals her name, but to dramatic effect this time. Even in her own narration, she plays second fiddle to her predecessor, the titular Rebecca de Winter.

First Person Strengths & Weaknesses

Strengths

This Point of View establishes a narrative intimacy between your Viewpoint Character and your Reader. Because that Viewpoint Character is also the Narrator, the story itself becomes a direct dialogue.

Basically, it’s a cheat code to engage your Reader’s attention and sympathies.

First Person is also a well-established Point of View, with examples spanning back to the dawn of the English novel. This gives it a long literary history to draw upon.

Weaknesses

Beware the underdeveloped narrator.

If your Viewpoint Character fails to communicate their personality in their narration, the First Person Point of View can fall flat. The Narrator might become an avatar or self-insert for the Reader, which is fine if that’s your intent. However, if you’re aiming for memorable characters, this POV runs the risk of undermining rather than enhancing those efforts.

It’s also the default Point of View for many authors, to the point that it’s earned a reputation of overuse. When executed well, it’s a tremendous asset, but when done poorly, it does your story no favors.

- What are your favorite 1st Person POV stories? Have you encountered any that showcase a creative or unusual use of this POV?

- What draws you to (or repels you from) this POV?

Up Next: Second Person Point of View

Index Page: Point of View