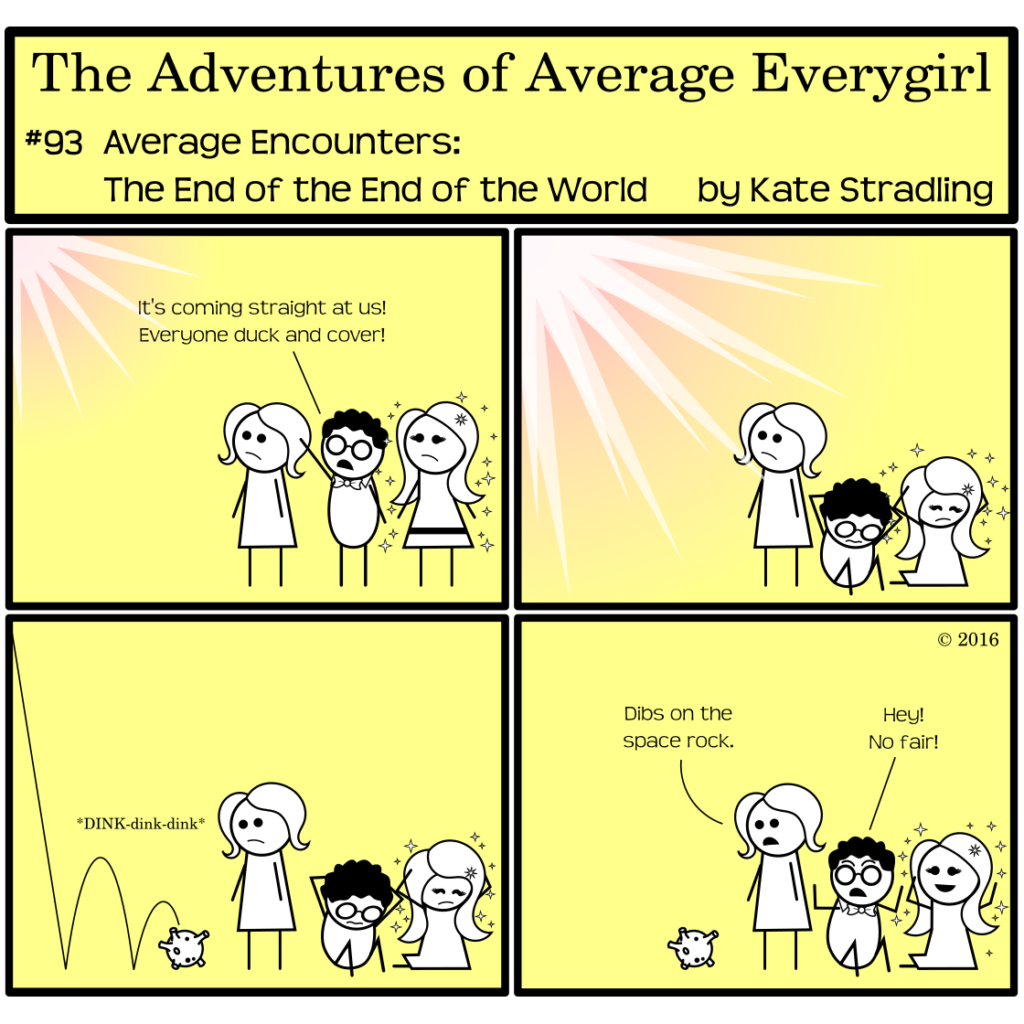

What’s this? An anticlimactic plot twist? Guilty as charged!

The Author-Audience Contract

An unwritten contract exists between every author and their audience. The author promises to take the audience somewhere new—to greater knowledge or fantastic lands—and the audience promises to go along for the ride. The lion’s share of the work lies on the author’s side. If they fail to engage with cunning word-craft, the audience has every right to abandon ship or—worse—to remain on board and snark through the whole trip.

Which can be grossly entertaining, I’ll be the first to admit. (MST3K, anyone? Coming soon to a Netflix near you!)

Generally, though, it’s never the author’s goal to inspire rampant mockery. The author-audience relationship is meant to be cooperative: author provides story, audience is entertained. One of these days I’m going to write a whole series of posts on the linguistic principle of cooperation. For now, suffice it to say that this cooperative relationship involves a delicate balancing act on the author’s part.

The savvy reader looks at every book as a puzzle to decipher. The savvy author looks at every reader as a customer to entertain. And that is where plot twists come into play.

The Garden Path

Plot twists, plainly defined, are the punchline to a joke you didn’t know you were being told. Sometimes the joke isn’t at all funny. Sometimes it’s horrific or heart-wrenching. The punchline catches you off-guard and sends you reeling. That moment of enlightenment, of surprise and delight or despair, is the ambrosia that author and audience both seek.

We sometimes refer to authors adept at plot twists as “leading [their audience] down the garden path.” The audience, in large part, signs up for this deception too, and if they don’t receive it, they can feel cheated in the end.

Which leads us to our worst offender…

Deus ex Machina, an Anticlimactic Device

Literally “God from the Machine,” this infamous plot device is the cheapest ploy on the block. It refers to a convention in Ancient Greek plays. Characters would become so entangled in their dire and twisted circumstances that their only way out was through divine intervention in the form of a god lowered onto the stage via crane.

Modern versions don’t typically involve deities or pulley systems. They might lean on happenstance or good fortune that drops out of the blue to save the day. Sometimes, though, they are simply a conflict too easily resolved: a villain that isn’t as bad as they seem, a “catastrophe” with minimal impact, or the ever-popular “it was all a dream” anticlimactic cop-out.

These and their ilk are the literary equivalents of expecting a decadent truffle and biting into a stale marshmallow instead.

But sometimes, from the author’s perspective, deus ex machina is oh-so-tempting. Especially in that first draft stage when you get to the point where you just want to set the whole manuscript on fire and walk away.

*cough*

It’s hard work to embroil one’s characters in turmoil and ruin. It’s harder work to get them believably back out again. For the sake of the author-audience relationship, though, plotting always represents time well spent.

***

PS – Happy Birthday to Average Everygirl. Today marks a year from her Average debut, and what a long way she’s come.

Happy Birthday, Average!

Wheeee! Happy birthday, Average!

Comments are closed.