Nestled among the marked (or “dispreferred”) behaviors of discourse we find a lovely little linguistic feature known as “hedging.” Hedging is the default refuge of anyone who doesn’t want to be held 100% accountable for what they say. The speaker tempers their words via modals or modifiers to lessen the impact of their speech, thereby creating a verbal trap door through which they can escape should the need arise.

It’s the linguistic equivalent of tiptoeing and a useful hallmark of lawyers, politicians, bloggers, and anyone else who might worry about getting caught in a lie by their own soundbites.

Shifty behavior isn’t the only factor that lends towards hedging. Politeness plays a strong part as well. You don’t want to speak in bald absolutes? There’s a hedge for that.

Modal Hedges

Modals provide a ready means of hedging. Compare the solid, reliable sense inherent in can, will, shall, and must with the weaselly, conditional sense of may, might, could, should, and would. You can almost hear the retractions formulating in a speaker’s mind:

“I told you I might help, not that I will.”

As modals, by their definition, indicate a speaker’s mood toward the statement they utter, use of the conditional models is a dead giveaway for a hedge. The speaker may follow through, but then again, they might not.

Verbal Hedges

Verbal hedges come in at least two varieties. The first is the pull-your-punch linking verbs that people like to substitute for the solid “be”:

- seem: “She seems nice.” (I don’t know if she actually is, but she seems that way right now, so don’t hold me accountable if she turns out to be a massive jerk.)

- appear: “It appears we have an agreement.” (We have one, but I don’t want to trample on your sensibilities by declaring is so boldly, in case you’re having second thoughts.)

- look: “He looks angry.” (Every visual cue for anger is there, but there’s a slight chance he has one of those angry faces, so I won’t definitively label him as being angry just yet.)

The second type is a shell verb that dilutes the main verb of a sentence to allow for exceptions to the statement. For example,

- tend to: “I tend to shriek when I’m scared.”

- try to: “I try to obey traffic laws.”

Such hedges can be useful, but remember: the longer the verb phrase of a sentence, the weaker its effect. In strong, efficient writing, verbal hedges get the boot.

Adverbial and Adjectival Hedges

Adverbial and adjectival hedges are, as their name implies, adverbs, adjectives, or adverbial phrases that qualify another lexical part of speech (noun, verb, adjective, adverb, or preposition). They come in many varieties. For example,

Modifiers of Size

Some adverbial and adjectival hedges reflect “smallness” in their literal meaning, the better to minimize the rhetorical impact of the word or message they modify:

- a little: “I may be a little late.” (“I won’t be there on time, but it’s nothing to get upset about.”)

- a bit: “Your voice is a bit loud.” (“Tone it down, Brunhilda.”)

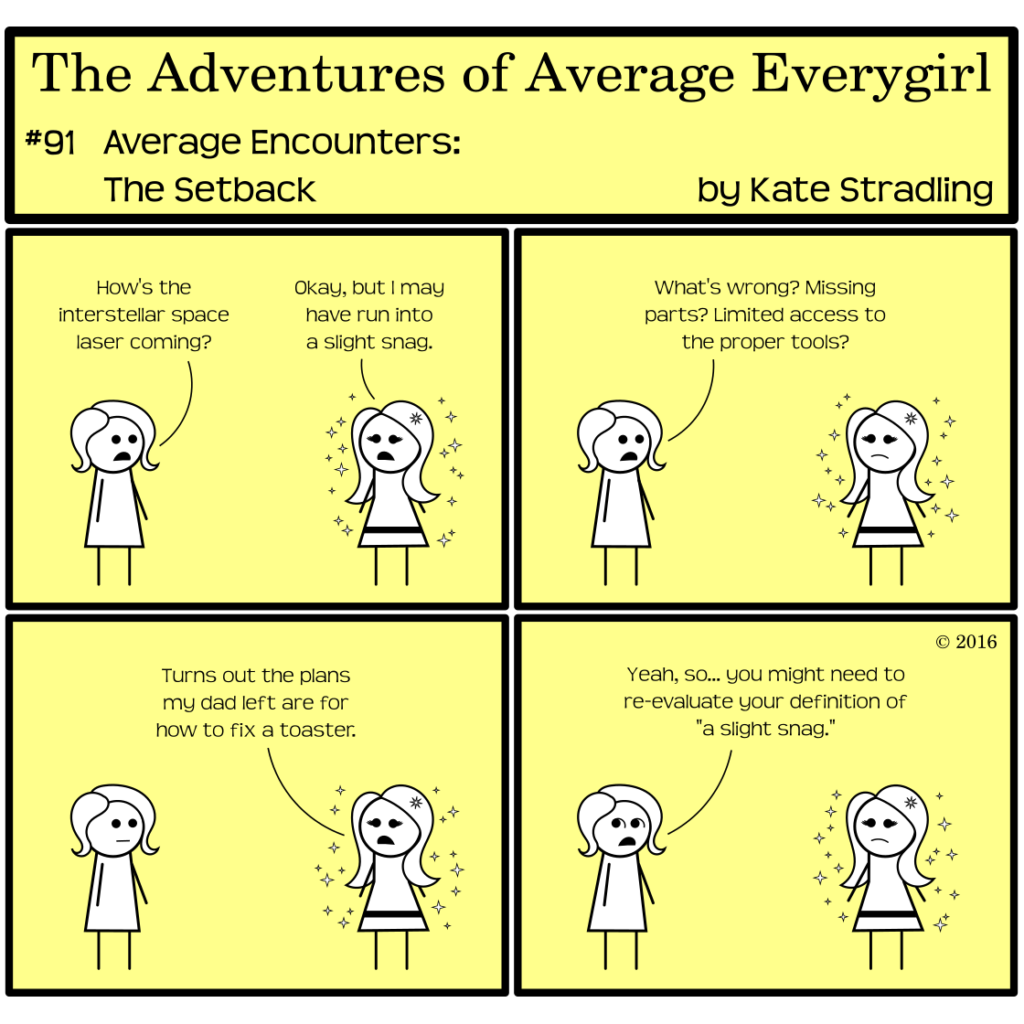

- slight: “We’ve run into a slight snag.” (“Something’s gone wrong. Terribly, terribly wrong.”)

- at least: “I called your name at least five times.” (“I lost count after five, but there were more than that. Or I’m exaggerating to make you feel bad.”)

Modifiers of Type

Others reflect “variety”:

- kind of: “I’m kind of happy.” (“I’m happy, but saying it outright is too much.”)

- sort of: “You’re sort of a jerk.” (“You’re totally a jerk. Mend your ways.”)

Modifiers of Time

The “frequency” adverbs often and sometimes serve to temper their absolute counterparts, always and never.

Stacking Hedges

My personal favorite with adverbial hedges is when they pile up on each other, à la kinda sorta (“I kinda sorta like you, Jimmy.” *blushblushblush*) or when they directly contradict the adverb they’re modifying.

Kind of really, my love, I’m looking at you. “I’m kind of really annoyed right now” actually means “I’m really, really annoyed right now, but I’m tempering one of those reallys with a kind of because I’m showing restraint, but if you don’t take the cue I might end up wringing your neck.”

Yes, in a strange twist of language, kind of really is a hedge that augments and diminishes at the same time, people.

(Which is why I love it so.)

When it comes to narrative writing, adverbial and adjectival hedges are mostly superfluous (YSWIDT, haha?) and can be edited out. A slight snag is a snag. A minor hiccup is a hiccup. And if you’re a little late, you’re late. Period. No modifiers necessary.

Except when you kind of really need to, I mean. And then it’s pretty much okay.