Virtue, unfortunately, is too often disposable in a doomsday plot. We’ve all seen it: two people of casual acquaintance thrown into a story line that involves instant death bearing down upon them. And suddenly, in the midst of calamity, voila! A lurrrve subplot is born!

Sure, they might grapple with a token moral dilemma—”Should we? Should we not?”—but inevitably, the qualms recede as the end draws nigh. Principles aren’t that important, you guys.

This phenomenon of expendable virtue can crop up in pretty much any impending-death scenario, but the cataclysmic doomsday genre allows it to flourish. It encourages its characters to participate in an angst-filled battle against regret and to arrive upon its “seize the day” solution.

Which is ironic, because impromptu hook-ups are more often a cause of regret rather than a means of avoiding it. But I digress.

I have issues with this subplot for several reasons, three of which I’ll here discuss.

1. The “Expendable Virtue” subplot illustrates selfishness.

I get the whole “unfulfilled love” vein of regrets, but intimacy born of impulse is the opposite of love. It’s a self-serving act, and too often it comes with an “anyone will do” undertone. Person A solicits Person B to satisfy their own desires. “But Person A has always secretly loved Person B,” you might contend.

Yeah, sorry. It still rings hollow. It would hold a lot more weight for me if Person A only wanted to spend time with Person B and wasn’t angling for some action, but that’s rarely the case.

2. Characters in this subplot can come across as predatory.

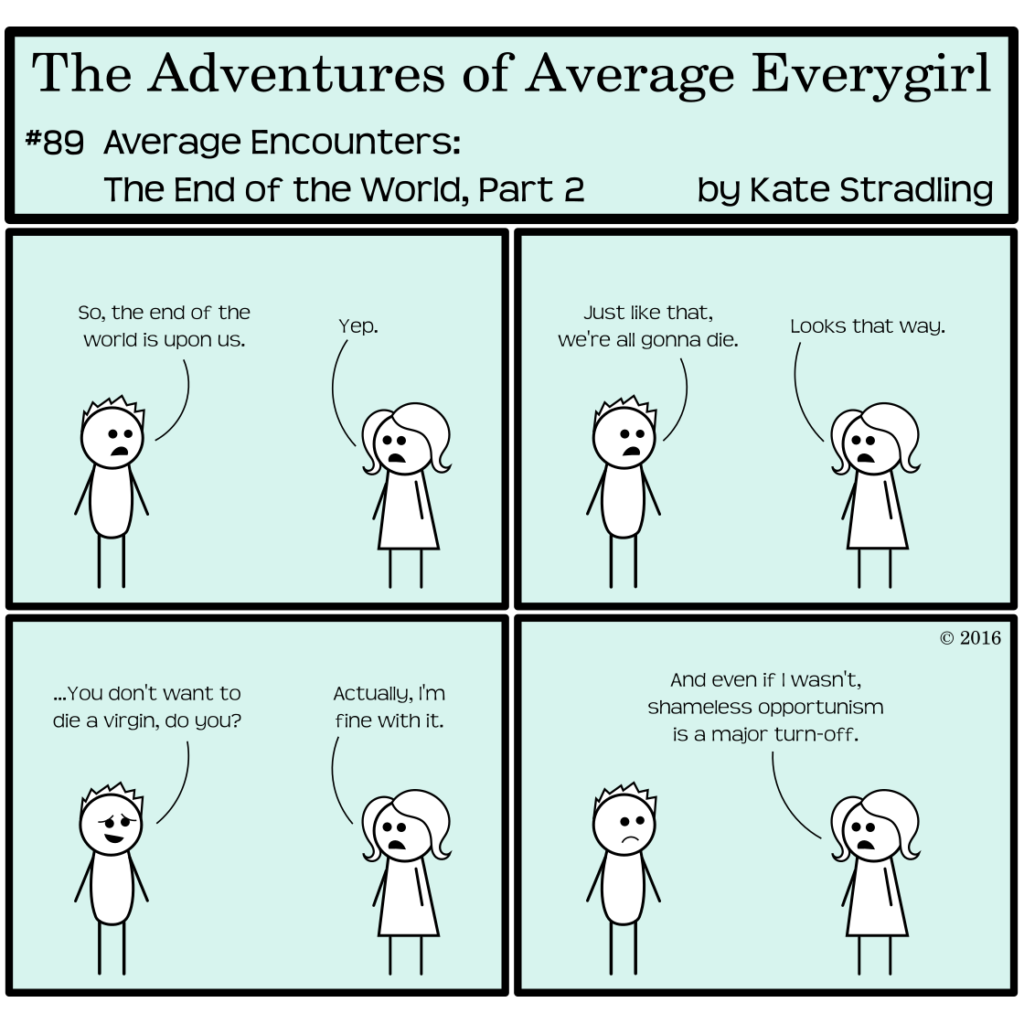

This is particularly true when one of the parties involved is at all reluctant. One partner pressuring the other for intimacy creates an unequal power balance, and using impending doom as a means of coercion is a special brand of vile.

That’s something captors do to hostages. It’s what abusers do to their victims. It’s a mind game. “You don’t want to have these consequences, do you? You should obey me.”

Yuck.

3. Its paradigm is fundamentally godless.

This one is probably fine for readers with atheist or agnostic leanings. I don’t fit in that category, but I get the logic. If death is certain and there’s nothing beyond, why not engage in behavior that might otherwise be reckless or ill-advised?

Except that there’s a whole list of behaviors we should never engage in under any circumstances: arson, murder, rape, molestation, animal cruelty, and so forth. And no, I’m not drawing a parallel between consensual sex and criminal activity, but when the argument boils down to, “Let’s do this because there will be no consequences,” the line between right and wrong no longer exists. Virtue of any kind vanishes. Why shouldn’t a character go on a murder spree if there won’t be any consequences?

(Incidentally, that could be a fascinating subplot for a doomsday story, and a heck of a lot more original than the Desperate Awkward Love trope.)

Rationalizing the Abandonment of Virtue

The moral dilemma variation to this subplot only enhances the scenario’s inherent godlessness. In the face of impending destruction, characters cast aside life-long beliefs and embrace the philosophy of “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die”—a philosophy that only works if there’s no final reckoning in the Great Beyond.

Frankly, abandonment of faith and principles is the last thing I want to see in any character’s closing hours. That’s depressing, even more so than an Imminent Fiery Death.

I’d much rather see kindness, hope, encouragement, people being decent to one another, reconnecting with family, mending fences. A million potential regrets would loom over someone’s head in a doomsday scenario, but love—true, lasting love for family and dearest friends—dominates that list.

Our culture is obsessed with romance, though, and spur-of-the-moment intimacy marks the apex of that ideal. So, we get hackneyed subplots about gangly teens trying to fulfill their warped sense of love, validation, and lost adulthood instead.

Yay.

*gags*

Principles are not meant to be disposable. They’re supposed to remain constant regardless of external circumstances. The whole “You don’t want to die a virgin, do you?” line of persuasion should lead to one obvious answer: “Why not? That’s the way I lived.”

But there’s no drama in that, only dignity—which is perhaps the most underrated virtue of all.

<3

🙂

Comments are closed.