If you’re anything like me, you do a lot of things in life “for the experience.”

“Hey, yeah, let’s try that roller coaster where you hang suspended with your feet dangling out over nothing.”

“Wheat grass? Sure, give me a shot of that.”

“Ice skating? Why not?”

(For the record, I’ve never been ice skating. I do know my limits.)

The world is full of so many sights and sounds and smells that “for the experience” opens up a playground of learning. We travel “for the experience.” We take internships “for the experience.” Experience broadens our understanding and refines our ability to empathize.

Limitations on “For the Experience”

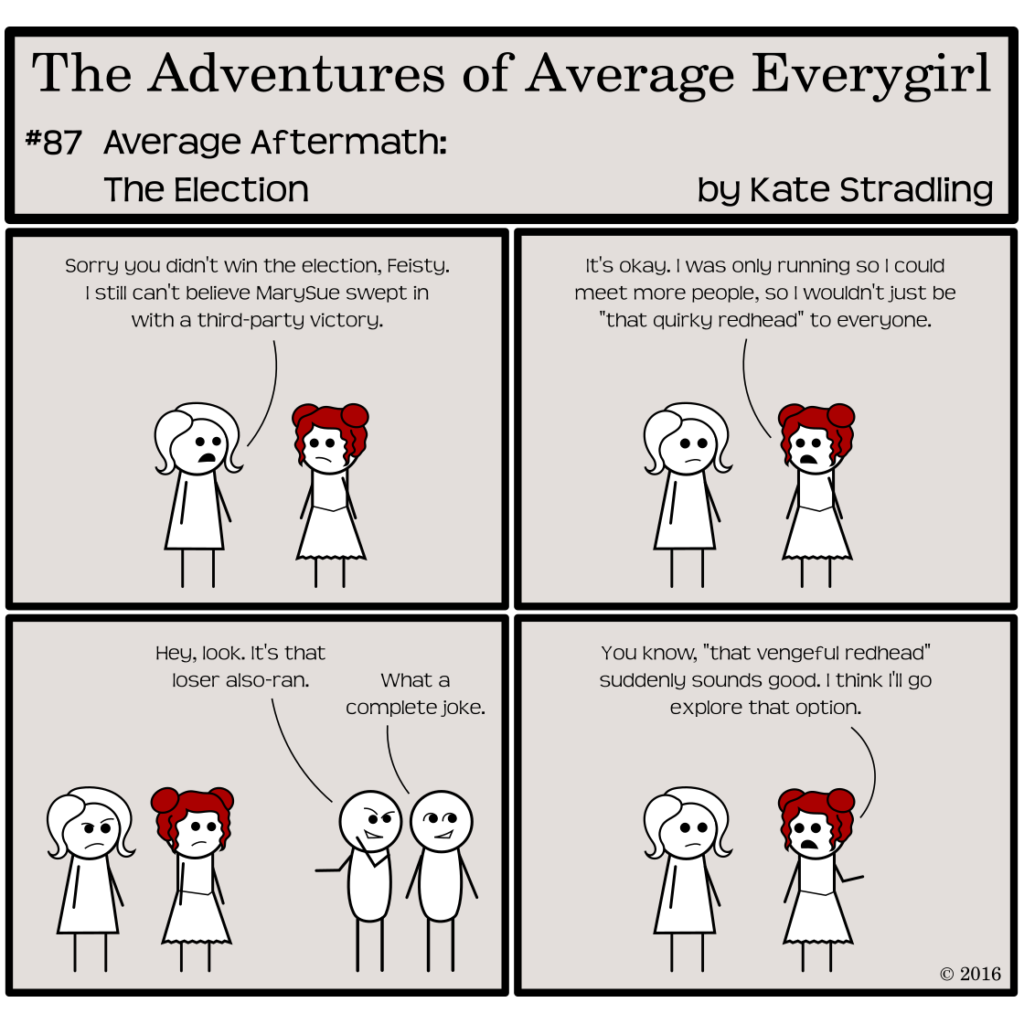

One place this line doesn’t work, however, is in any activity that involves competition. Sure, someone may go into it thinking, “I’m excited to see what this is like,” with absolutely no expectation of winning—or of even placing—but in the aftermath, they’re not allowed to talk about that.

The instant they lose, “for the experience” becomes a semi-pathetic excuse.

Person A: “Oh, I joined that tournament for the experience of it. It was great.”

Person B: “Yeah, sure you did, buddy.”

Person A: “No, really. I knew I didn’t have a chance at winning. I didn’t even check the leaderboard.”

Person B: “Uh-huh. You know, it’s okay that you lost. The winners were all really good.”

Person A: “I know it’s okay, and I wasn’t trying to win. I just wanted to have some fun.”

Person B: “Right. Okay.”

Somehow, the more Person A insists, the less truthful they sound. “The lady doth protest too much, methinks,” as Shakespeare penned.

When More Is Less Believable

Certain patterns of speech fall under what pragmatists term “marked” or “dispreferred” behaviors. Repetition is one of these, along with hesitations, hedges, false starts, and wordiness. Such dispreferred behaviors run counter to the listener’s conversational expectations and thereby signal the listener to question the speaker’s truthfulness.

Truth, you see, is generally straightforward and non-excuse-making.

Generally.

Thus, when the listener already has cause to question a line of speech—as in the case where someone claims disinterest for winning a competition in which they participated when the very purpose of competition is to compete—then repetition of the information only augments that skepticism all the more.

So where does that leave those of us who really do engage in such activities “for the experience”?

One method is to acknowledge the failure outright in the aftermath. This disarms the assumption that the speaker is making excuses for their weakness.

“Yeah, I failed spectacularly, but it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, you know?”

or

“I had no business being among all those greats. I was so lucky just to be on the same playing field.”

or

“On the one hand, it sucks that I didn’t stand a chance, but on the other, I learned a ton.”

Humility goes a long way toward establishing bona fide communication. Paradoxically, we save face by undercutting ourselves from the start rather than allowing someone else to do it for us. In contrast, downplaying failure, even when it was genuinely expected, comes across as prideful: the speaker frames themselves as above competition, above the plebeian masses who strive to succeed in that venue.

They invite skepticism, in other words.

Experience the Nuance

Human communication abounds with these built-in nuances. We instinctively sift and evaluate the information we receive from others. We filter the information we send. Like a dance, the steps are pre-determined, and anything out of line may well tromp on toes.

Also like a dance, all the study in the world won’t perfect the art. You have to get out on the floor and practice and fail and practice again.

You know. For the experience.

Because sometimes that’s not just the best way to learn; it’s the only way.