When many people hear the word “propaganda” they immediately think of war and politics and Nazi Germany, which took this form of communication to such an extreme level as to shove it over into the perceived negative side of the rhetorical spectrum.

The Nazis popularized the Big Lie technique to dastardly effect. Nowadays, when you call something propaganda, it invokes that bygone era and casts a shade of corruption and deceit upon the item in question—or upon you for calling it out.

But, truthfully, we’re surrounded by propaganda almost 24-7.

Language in Harmony

In Rhetoric, the philosopher Aristotle introduces three rhetorical proofs that work in harmony to create good rhetoric: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos.

- Ethos refers to moral character; the term is directly related to “ethics.” A speaker with good ethos fixes themselves and their arguments on solid moral ground, demonstrating an honest nature and instilling their audience with trust.

- Pathos refers to emotion; the term is cousin to “pathetic,” which originally meant “full of feeling” rather than “something contemptible or deserving pity.” A good rhetorician conveys their emotion to engage their audience more fully.

- Logos, as you can probably guess, refers to logic; good rhetoric must be rational and well-reasoned. It provides sufficient and consistent evidence for its thesis.

These three elements, working together, create solid, persuasive communication.

Propaganda, or Language Out of Balance

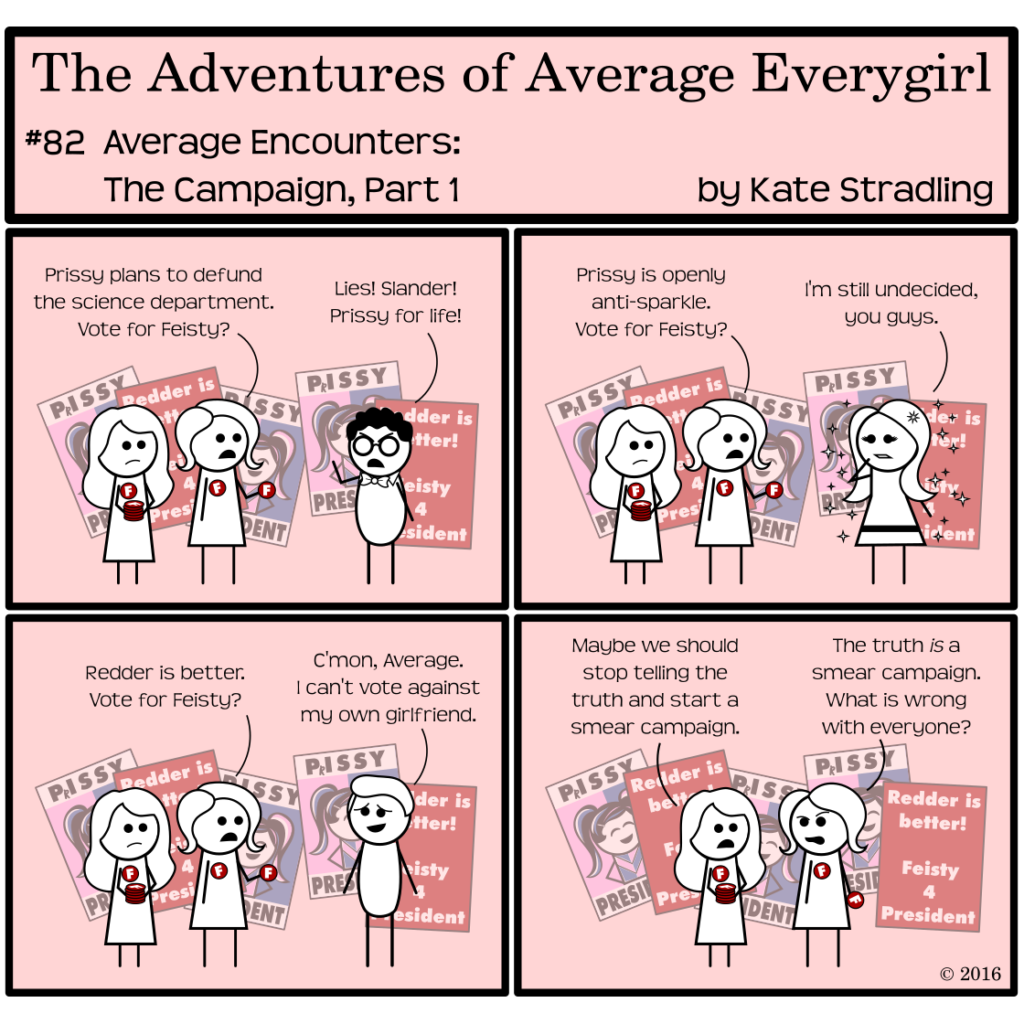

Propaganda is rhetoric at an extreme, where the Ethos-Pathos-Logos triangle gets skewed into a false caricature of its former self.

Ethos gets thrown out the window from the start: the propagandist seeks to manipulate first and foremost—whether it’s convincing you to support a cause or to buy a product or to vote for one candidate over another. Propaganda has no interest in unbiased information because it doesn’t trust you to make up your own mind. (It’s already made up your mind for you, thank you very much.)

With ethos out of the way, Pathos reigns supreme. Propaganda runs amok through the emotional spectrum. It incites fear, it projects happiness, it foments anger and invokes pride. And it does all of these in exaggerated form. “Look at all the joy this awesome new product will bring to your life!” “Don’t vote for her! She’ll throw grandma off a cliff!” “Support this issue now and your grandchildren will praise and adore you!”

Logos abandons reason and morphs into the part of the shifty sidekick. Evidence may or may not enter the argument. It may or may not be relevant. It is inaccurate, over-simplified, and/or inconsistent. The argument sets a double standard, with the speaker pointing fingers at others while holding no accountability for him- or herself.

And when this type of communication succeeds, it’s because we as humans by default assume that the speaker’s Ethos-Pathos-Logos triangle is intact.

Questioning the Narrative

Some questions to pose when confronted with a piece of suspected propaganda:

- What is the speaker’s motive?

- What emotions does this argument invoke? Are they balanced against its ethics and logic, or does emotion take center stage?

- Is there evidence provided? If so, is it relevant, accurate, and sufficient?

- Is the argument consistent? Do its claims match real-world results?

- Does the speaker maintain the same standards they advocate?

It’s so much easier to accept communication as bona fide than to have to question every piece of information we receive. Even so, a little skepticism will go a long way in today’s world. Propaganda clots the airwaves and clutters the Internet. It bombards us in visual and verbal form. It manipulates our minds and befuddles our senses.

But don’t take my word for it. That would defeat the purpose of this post.

Love it! I have had the same thought process because of the drivel I find in social media these days. You brought my thoughts into three very simple concepts. Thanks!

This explains social media to a tee. Throwing out Ethos, using Pathos to get you incited and capture your attention and limiting the Logos to only those things that prove your point. And as the old saying goes “numbers don’t lie, but liars use numbers,” we see it happen with words and events too.

Yes! This is all over social media. It’s also the foundation of the so-called “click bait” headlines: appeal to emotions, leave out pertinent details to garner a click-through (and then sometimes leave them out entirely from the actual article), and collect on the ad revenue that results.

Comments are closed.