The Makeover Fairy (AKA the Fairy Godmother) exists in a story for the sole purpose of transforming the main character in a flash, and at a pivotal moment. The classic example for this trope is, of course, Cinderella, where the fairy godmother appears out of nowhere to cast a glamour over her ill-treated beneficiary.

Much has already been said about the ham-handed convenience of such a fairy godmother, who allows Cinderella to live through years of abuse and injustice before she bothers to show up. I prefer to attribute her unreliability to the capricious nature of fairies in general. Why should she have come earlier? Was there ever a fab party on the line before?

(Of course there wasn’t. And who needs a ball gown for boring old life?)

Unique as a Way of Life

This breed of character marches to the beat of its own drum. Maybe it’s a fashion-forward co-worker, or the trendy-goth sister of the love interest. Maybe it’s Leonardo da Vinci. Regardless, the Makeover Fairy receives token acknowledgement within the story, but their only real purpose lies in helping the main character look ah-mazing.

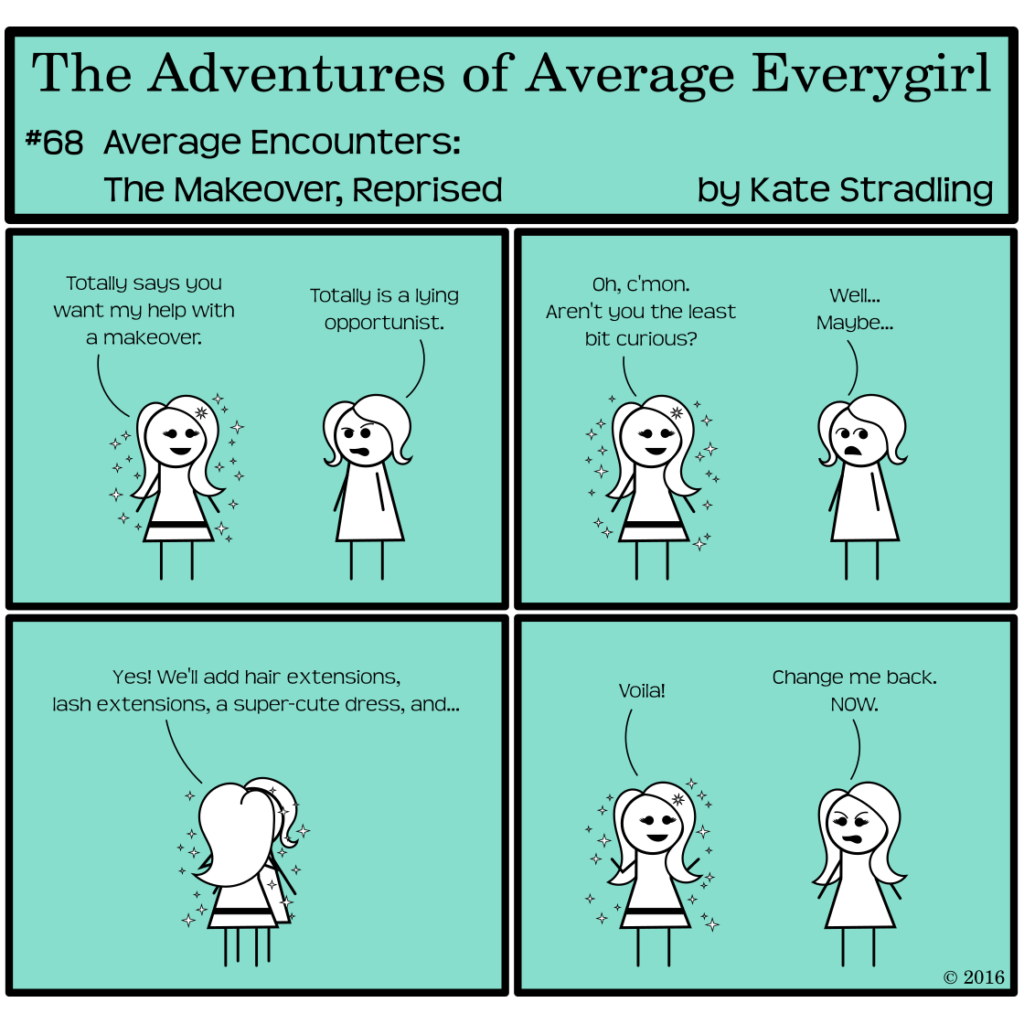

They swoop in—with or without the character’s consent—work their magic, and then gleefully send their human canvas out into the world. They don’t typically attend the Grand Event themselves. Their motives are altruistic, with no expectation of favors returned.

If the story is a solar system and the main character is the sun, the Makeover Fairy is a comet, circling in for a dazzling close encounter before rocketing back out of the way again.

It’s all very tidy.

Makeover Mechanics

The unsolicited makeover lends to an air of humility for the main character. She didn’t go looking for beauty so she’s not vain, you see. She’s pure-hearted, and the universe rewards her for it.

She’s also beautiful to begin with. You notice that she doesn’t need any pounds shaved or teeth straightened. Her aesthetic shortcomings amount to a few cosmetic tweaks. In the rare instance where this is not the case, the character’s transformation can be summed into a quick montage of morning jogs and salads for lunch, as though a complete lifestyle change only requires the decision itself and a peppy playlist.

If only real life were that easy.

But we don’t turn to fiction for real life. We turn for an escape, and one of the most seductive messages of escapism is that some exterior source is going to intervene and grant all of our fondest dreams, with little to no effort on our part.

It’s a lie, but seduction typically is. The true pattern of hard work appears quite dull in comparison.