The victim in a Whodunnit scenario will gravitate toward two extremes:

- Everyone hated them. Motives for murder abound and winnowing down the suspects will be a task unto itself.

- Everyone loved them. Motives for murder are nonexistent and cobbling together a list of suspects will also be a task unto itself.

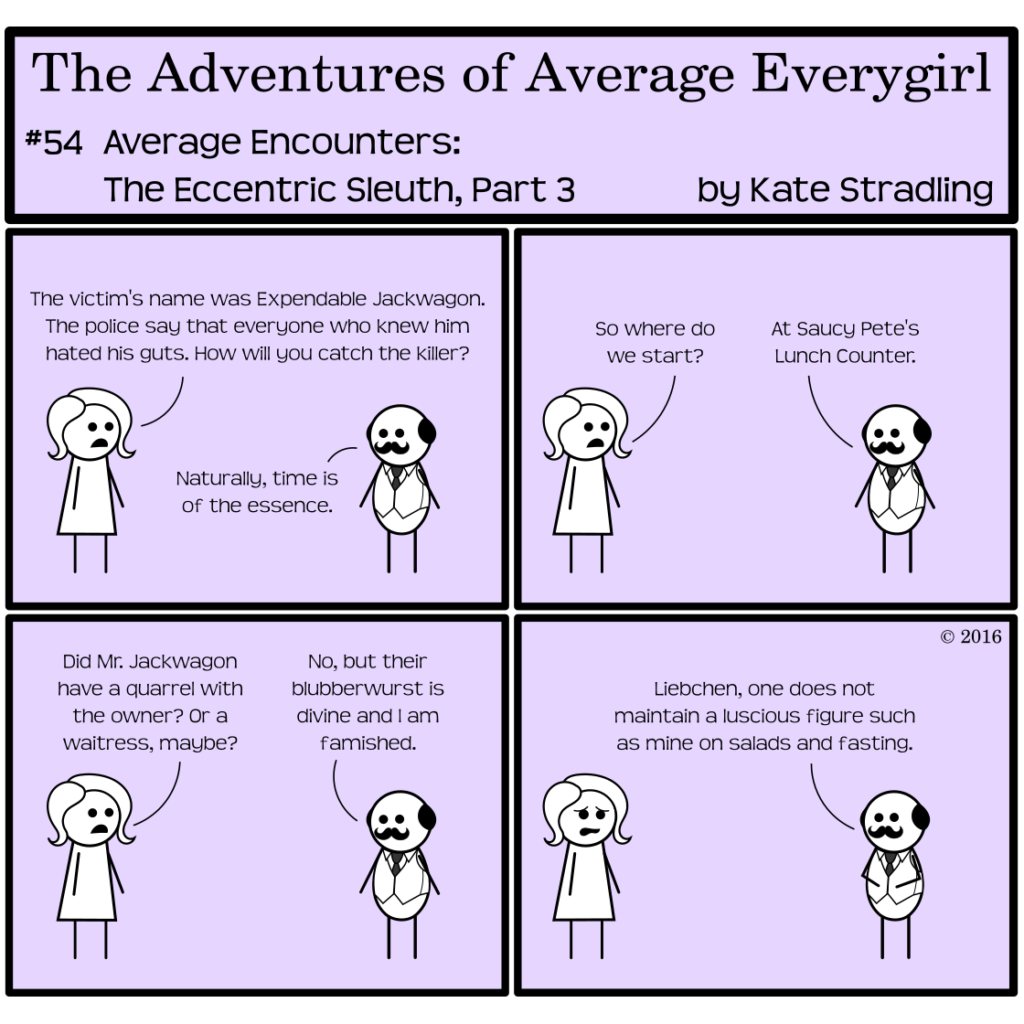

An Object of Hate

The first extreme is the emotionally easy route to take. When the victim is an expendable jackwagon, no one really mourns or misses them for long. The detective gets thematic commentary from suspects:

- “Yeah, I hated him, and I’m glad he’s dead.”

- “I wish I’d killed him. I’d like to thank whoever pulled the trigger.”

- “I’ll admit I’m not crying over his loss, but I’m not the one who did it.”

There’s also, typically, at least one suspect of the lot who will protest that they loved or valued the victim:

- “Sure, he was a louse, but he was my louse.”

- “He wasn’t as bad as everyone thinks.”

- “I knew a side of him that no one else did.”

Whether they’re telling the truth remains among the mysteries to solve.

A Victim Beloved

On the other end of the spectrum, when everyone loves the victim, the detective might uncover sordid secrets hidden beneath that devoted façade—secrets harbored by the victim or the loved ones who profess to miss them. A motive, or a dozen motives, can emerge in this systematic search. The killer’s checkered past or twisted psychopathy comes to light, and the loved ones mourn all the more.

This second extreme, the emotionally difficult extreme, forces the reader to look inward, to cherish life and relationships. We can cast aside the expendable jackwagon with the end of the book; the beloved victim stays with us beyond that.

And sometimes, the situation surrounding the victim’s death—regardless of whether they were loved or hated—makes a lasting impression upon our minds.

Master of Victimizing

Thus we come to the Patron Saint of Murder Mysteries: Dame Agatha Christie. Her corpus of work covers a full range on this victim spectrum. Among her dead are vicars, blackmailers, spinsters, secretaries, butlers, socialites, criminals, and children. She pulls no punches when it comes to killing off characters, a trait that is both admirable and terrifying.

A few of her memorable victims:

- Reverend Babbington, Three Act Tragedy (aka A Murder in Three Acts): A small-town curate with no known enemies, killed by nicotine poison in his drink at a cocktail party.

- Linnet Ridgeway Doyle, Death on the Nile: A rich, lovely newlywed, shot in her bed on a Nile River cruise ship.

- Joyce Reynolds, Halowe’en Party: A thirteen-year-old girl, drowned in an apple-bobbing barrel at a Halloween Party.

These three victims provide examples of three different criminal motives: one based on happenstance, one on long-term planning, and one on the impulse of the moment. All three deaths leave the reader with a sick knot in their stomach, especially when the killer emerges from the list of suspects.

This is not the case with all of Christie’s victims, however. Some deserve their fate and receive no mourning whatsoever. (See And Then There Were None for the quintessential example of this. It’s widely considered the best mystery novel ever written. And it left me squeamish for a week afterward.)

Christie’s brutal efficiency when it comes to murdering her own characters plays only part of her genius. She’s brutal with her killers as well.

But that’s a topic for another day.