I was raised on the King James Version of The Bible (the good ol’ KJV). In addition to its spiritual tutelage, this translation quite nicely programmed my brain with archaic language structures, a blessing for which I am eternally grateful.

Because, apparently, the distinctions between thou/thee and ye/you are not all that easy to pick up or keep track of (to say nothing of the 2nd and 3rd person agreement markers on verbs).

My parents taught me to pray using thou and thee to address the Lord. It’s a custom in my religion, though members follow it to varying degrees depending on how comfortable they are with these archaic pronouns (and there’s certainly nothing wrong with addressing Him with the modern you). We even hear on occasion that use of this bygone form of address shows a heightened reverence and respect toward deity.

By its very nature, archaic language, especially that associated with religious texts, takes on rhetorical features of formality, respect, perhaps even antiquated stuffiness.

The thou/thee/thy/thine of yesteryear, however, was anything but formal.

In the Old English period, the distinction between thou/thee and ye/you (or þu/þe and ge/eow, as they then appeared) was simple. Thou/thee referred to one person. Ye/you referred to more than one.

(Fun fact: There was also a dual case of pronouns in OE—git/inc in the 2nd person—that served to address exactly two persons, but it was in decline long before the end of that era, with only 1st and 2nd person forms attested.)

The singular/plural distinction between these two sets of pronouns suffered a heavy blow in A.D. 1066. For all you non-linguist, non-historians out there, that was the year Guillaume le Bâtard decided he’d had enough of his derogatory surname and crossed the Channel. He slaughtered Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, and called himself William the Conqueror from that point onward.

And he brought his Norman French with him, forever changing the linguistic landscape of the British Isles.

French, like English of yore, has distinct 2nd person singular and plural pronouns: tu and vous. There’s an added element to these pronouns, however: familiarity and politeness. If you are being polite, you always use the plural pronoun, vous. They even have specific verbs to request or correct pronoun usage:

- tutoyer (“On peut se tutoyer?” = “May I address you with the informal tu?”)

- vouvoyer (“Ne me vouvoie pas.” = “Don’t address me with the formal vous.”)

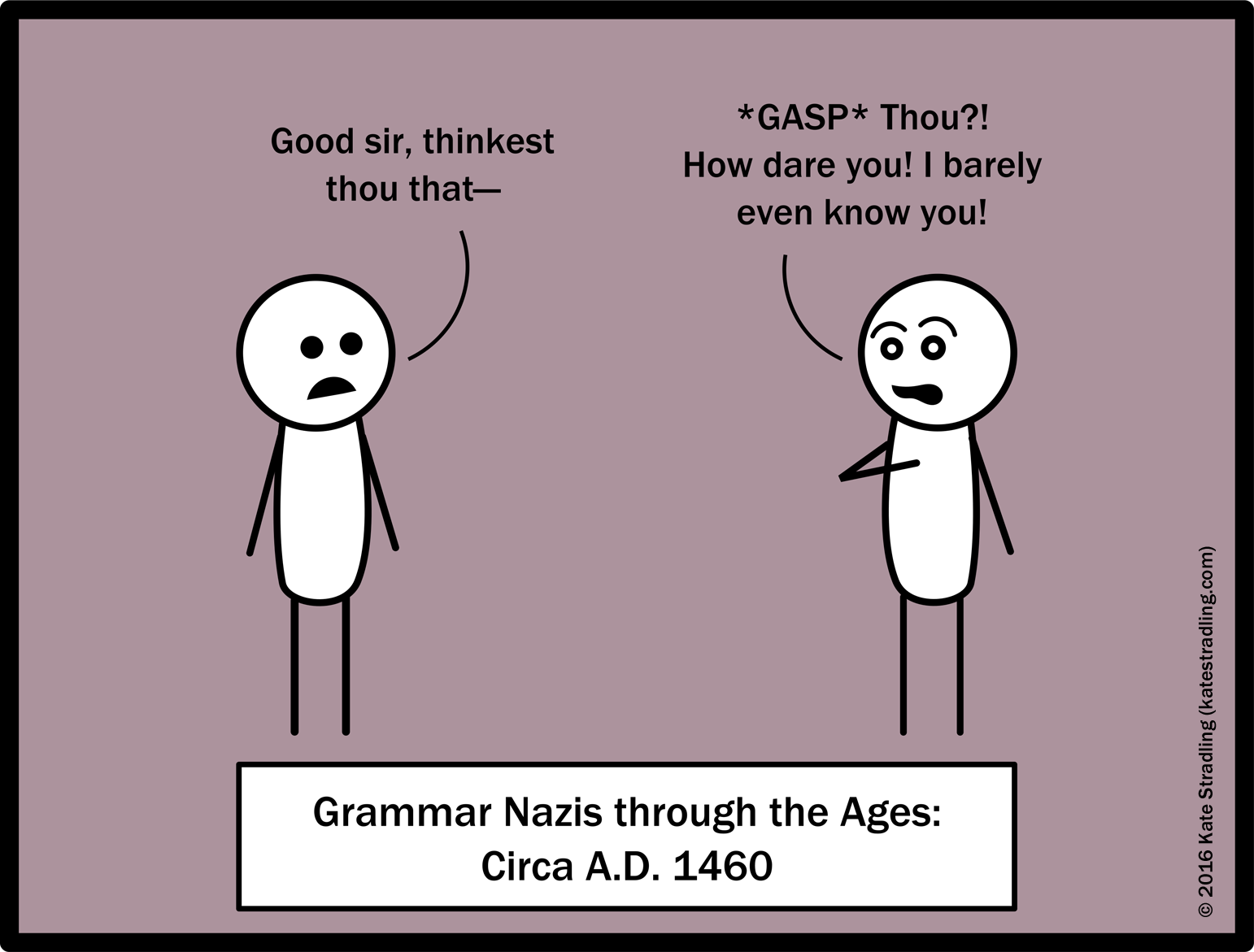

This familiar/polite distinction shows up in Middle English. Thou shifts from being merely singular to also indicating a close relationship. Ye picks up the slack for singular polite communication (and quickly gets absorbed into its object form, you).

And so begins the downward spiral of thou into obscurity.

Once politeness came into play, the familiar form fell out of use. It was already well into its decline in the 1520s when William Tyndale implemented it in his defiant English translation of the Bible. It was positively archaic in 1611 when the KJV was published. But since the King James scholars lifted their translation almost wholesale from Tyndale, its appearance there should shock no one.

Tyndale was a canny scholar, inspired, enlightened, determined, and far-seeing. Perhaps he used thee/thou/thy/thine simply to distinguish singular vs. plural pronoun translations. I prefer to think he chose his pronouns deliberately, though, that he recognized their colloquial use and the relationships they implied.

I respect the modern sense of reverence and formality that surrounds this archaic case, but peeling back that layer to the history that lies beneath communicates an added meaning for me. In addressing my God with thou and thee I acknowledge a kinship, an exquisitely personal relationship with the Only One who knows me perfectly, the Only One with whom politeness gives way to loving familiarity.

Those simple bygone pronouns, for me, stand as a symbol of the Lord’s grace, and of the beautiful, individual connection that binds me to Him.

Sometimes, politeness isn’t everything, and formality is only a façade.

Lovely! Thank you, Kate.

Thank you, Marsha! Glad you liked it.

I love all your English/Middle English/Old English posts, but I love this one BEST 😀

Thank you. It’s my favorite too. 🙂

This is beautiful.

Thanks, Shawnette. I love how even grammar can testify of God.

How beautiful is knowledge.

Indeed. “The glory of God is intelligence.”

Comments are closed.