Marriage conventions in the Regency period allow for a couple of fun—and perhaps alarming—tropes.

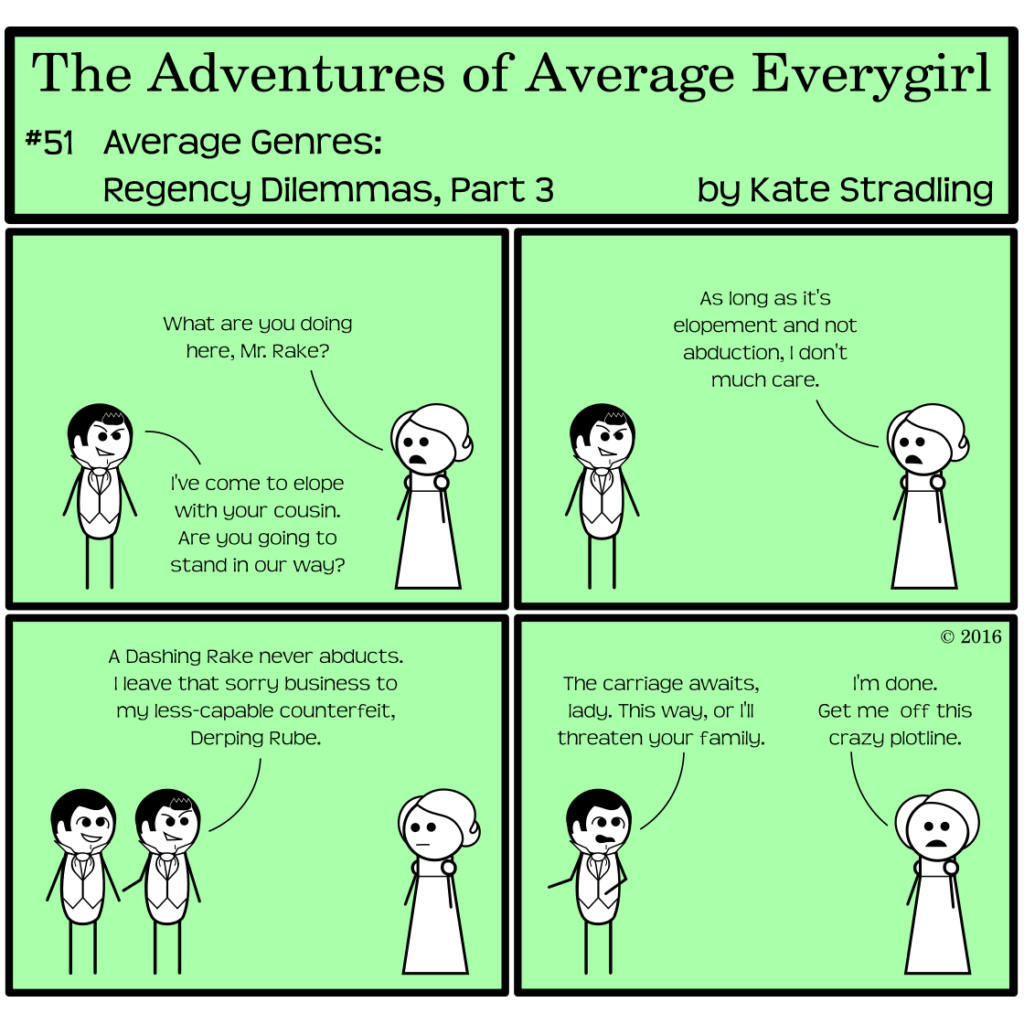

Marriage Trope #1: Elopement

Let’s talk about unintended consequences, shall we?

In 1753, the British Parliament passed Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, with the intention of curtailing marriages performed in secret. Prior to this act, English clergymen could perform marriages without the couple having to procure a license or post banns. The government would fine them for performing the ceremony in a parochial church house (thanks to an earlier Marriage Act), but the marriage was still valid.

And if they performed the marriage in London’s Fleet Prison, there was no fine at all (because of that earlier Marriage Act’s unintended consequences, hahaha).

Romantic, isn’t it? “Come, darling! Let’s run away to the prison house and get married amid the beggars and debtors!”

But that line must have worked. By the 1740s, roughly 12.5% of English marriages were Fleet Marriages, and their participants came from all walks of life, both rich and poor, upper and lower class.

The Marriage Act of 1753 was supposed to close this prison loophole, and it did.

Only to open another one: the Act didn’t apply to foreign marriages—including those performed in Scotland.

Cue a grand rush for the northern border, and the eventual emergence of a UK marriage icon: Gretna Green. This little border town lies along the road from London to Edinburgh. If a Regency romance talks of elopements, Gretna Green is the most likely destination, the nearest point where couples fleeing north could marry one another without the pesky need of parental consent or government sanctions.

(It’s kind of like the safe space in the game of Tag. Once you’ve crossed the line you can look back at the people chasing you and call, “Nanny-nanny-boo-boo! You ca-an’t catch me!”)

The journey was long, and the woman’s reputation would be in shambles before the couple arrived, but a quick ceremony would remedy all. So too for those who fled across the Channel from Dover to Calais, France: spend a night on a boat, get up the next morning in a foreign country, and all your marriage obstacles have magically disappeared!

Isn’t elopement wonderful?

The ease with which one might ruin a woman’s reputation in this period, though, provides an alternate and more salacious window for drama.

Marriage Trope #2: Abduction

When you pick up a Regency romance, you can lay odds that an abduction lies within those pages. Because of the era’s social constraints, the heroine’s virtue can be used against her as leverage to force her into an unwanted marriage, and without the perpetrator ever having to lay a finger on her. Passing a night unchaperoned in his near vicinity is enough to seal the deal.

If she’s a beautiful heiress, the chances of this scenario skyrocket. The abduction motif is almost built into the template alongside the devastatingly handsome hero and the array of social events.

And, more recently (i.e., post-Georgette Heyer), the guy performing the abduction is never quite up to snuff.

Maybe he’s crazy or deluded. He might be a fop, trying too hard to play the part of a Regency beau and falling short in his attempt, or he could be anywhere from dull to horrid in the looks department. One way or another, he’s defective, a social outlier framed in such a way that he poses no allure for the heroine or the reader.

Because the hero has to save her so they can finally confess their lurrrve to each other.

Yes, we’re playing literary football again, and Girl-as-Object is alive and well. In this scenario, however, no one’s rooting for the away team. And, true to his less-than-desirable image, the off-beat abductor never triumphs.

Which is a good thing. No one picks up a Regency wanting to trigger their depression.

I would like some more competent abductors, though. It would be okay if the guy was a handsome, cunning sociopath instead of a desperate, penniless fop. There’s no need to frame him in a way that makes him completely unsuitable as a love interest before the abduction ever occurs.

The abduction can do that job well enough on its own.

(And really, that seems like the best reason for including an abduction in the plot at all.)