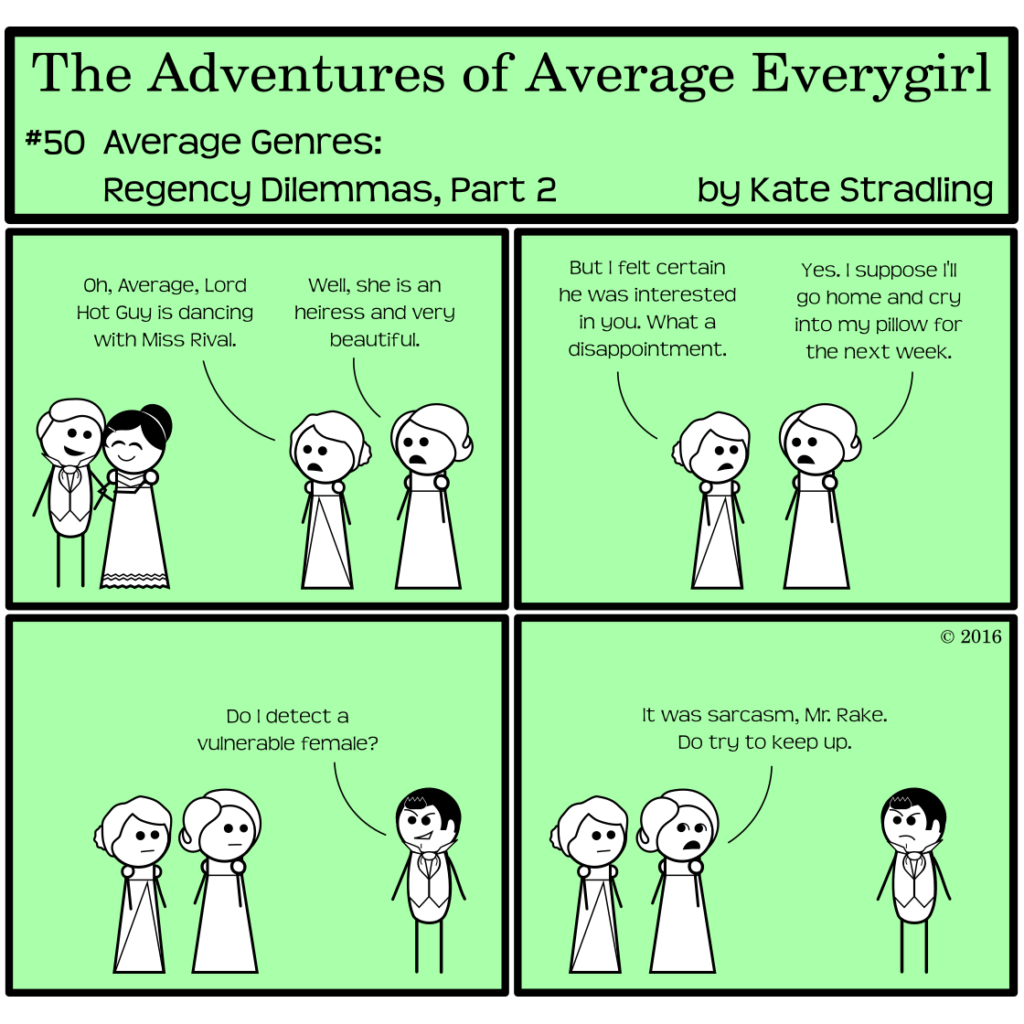

In Regency romance, any female rival is most likely a “diamond of the first water”: beautiful, poised, rich, accomplished, beautiful, well-dressed, beautiful. Did I mention that she’s beautiful? There’s a reason for that. Such stunning beauty ups the ante on a plain-Jane heroine, thereby making the heroine’s eventual triumph with the hero all that much sweeter.

Hero: My dear, you underestimate your beauty. You have the radiance of a thousand suns.

Heroine: You cannot mean it. I am so very plain.

Hero: No. You are infinitely more beautiful than any other woman in the world.

Heroine: *swoons*

Destined Couple: *smoochy-smoochy-smoochy*

Freckle-faced Reader: The ordinary girl won out over the beauty queen? Maybe it can happen to me, too! *SQUEEEEEEEEEE!!!*

This motif is not restricted to Regencies, of course. It runs rampant through the broader Romance genre, including YA novels with a romance side-plot. It all hails back, once again, to the Girl with Low Self-Esteem (that wretched, pervasive trope).

Beauty as a Benchmark

The emphasis on physical beauty demonstrates how shallow any set of characters are. Which is why it’s so at home in Regency novels: it’s the hallmark of an era where image is everything. Women are chattel, and their main objective is marriage, so of course the prettier packages will fetch a better buyer.

(The men can be as ugly as all get-out as long as they’re rich or humorous to make up for it. Different standards for different sexes.)

In a novel where the heroine has self-esteem, it doesn’t matter how pretty a rival might be. The heroine won’t make comparisons because her worth doesn’t hinge on outshining anyone else. She might even admire the other woman’s looks and acknowledge her superior beauty.

Because it’s not a threat.

It seems as though general literary preferences tip towards the plain-girl-defeats-beautiful-rival scenario, however. Maybe it’s because we instinctively want to root for an underdog. Or, maybe we each see ourselves as an underdog standing against the vast and oppressive world, and such stories bolster our confidence to go out and conquer. Maybe we all have inferiority complexes and like to see those who are “superior” made to eat crow in the end.

Maybe we all think of ourselves as plain.

(I mean, I’ve been looking at this same face in the mirror for decades now. How boring is that?)

Popular literature reflects a culture’s psychology. You want to know what the people of a certain era or area value? Examine the art and literature they produce. In it you might discover their hopes, their fears, their expectations on life…

And you might discover that they have a shallow obsession with image.

(Perhaps the Regency era is not so far removed from our own after all.)