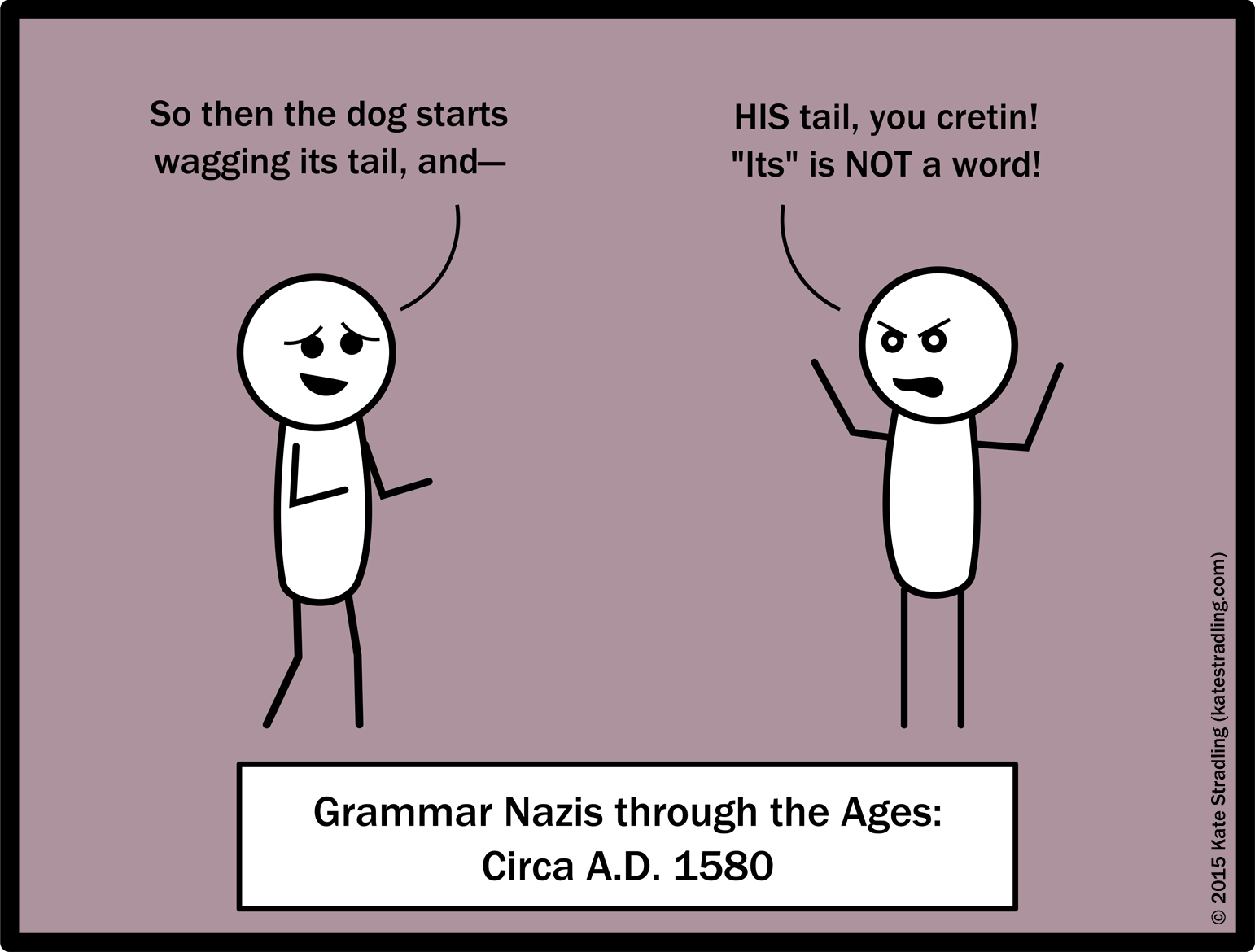

True story: “its” as a pronoun didn’t come around until Early Modern English. Up until the late sixteenth century, the 3rd-person gender-neutral possessive pronoun was “his.” (“Thereof” served the same function, though it appeared after the genitive object rather than before it: e.g., “the tail thereof.”)

Even better: when “its” finally did enter the language, it was frequently spelled “it’s” (including by Mr. William Shakespeare himself). Chew on that, high school English teachers everywhere.

Every time I see someone correcting someone else’s grammar, I instinctively think back to this and the many other changes our exquisite English language has undergone. And then I wonder how such people would have functioned in previous eras where those changes were more distinct.

But actually, prescriptivism probably didn’t exist in the 1500s—at least, not in the form with which we are most familiar. In the Early Modern English period, anything of value was written in Latin or French; the first English grammar wasn’t even published until 1586 (hat-tip to you, William Bullokar), and for a century afterward, successive English grammars were written in Latin.

Yes, Latin. English was a vulgar language. Only boors used it for scholarly writing.

Starting in the late 17th-century, scholars began to give English a little more credit. At that point, grammarians swept through and codified everything and tried to pattern our rules after Latin instead of Germanic structure. English words derived from Romance languages took on more prestige than those that came from good Old English (a belief preserved to this day in such mundane issues as “writer” vs. “author”: an “author” is so much more important, don’cha know, even though the only real difference between these two words is their etymology).

This is the era that chastised us for for splitting infinitives. (You literally can’t split an infinitive in Latin. It’s a single word instead of two.) It’s the era of inkhorn terms, those delightful absurdities. It is the great-grand-pappy that bred all the millions of self-appointed grammar gurus in the world today.

(The poor souls.)

Language changes. Trying to control that change is like trying to dam the Amazon with a handful of twigs. You can’t.

But that sure as heck doesn’t stop people from trying.

(Which is nice in its own way. I need a good laugh every now and then.)

Love. That is all. This makes me happy. 🙂

Hooray! Thank you! 😀

Comments are closed.