We find one of the longest battles in English linguistic history in that simple, problematic word “ask.” You wouldn’t think that three small letters could cause so much trouble, but you would be wrong. Nowadays, someone using the pronunciation of “aks” (or “ax,” as it’s commonly written) gets painted as ignorant or lower class.

When really, it’s been a dialect issue from the beginning.

If you look up “ask” in the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymology section will provide you with 40+ different spellings that have been used over the past thousand years. Old English used both acsian and ascian (but note that it’s also generally accepted that “sc” was pronounced like modern “sh” rather than “sk”). Middle English, true to its nature, has a dozen or more variations, depending on which dialect of English the written work comes from, and a good number of them use the letter x.

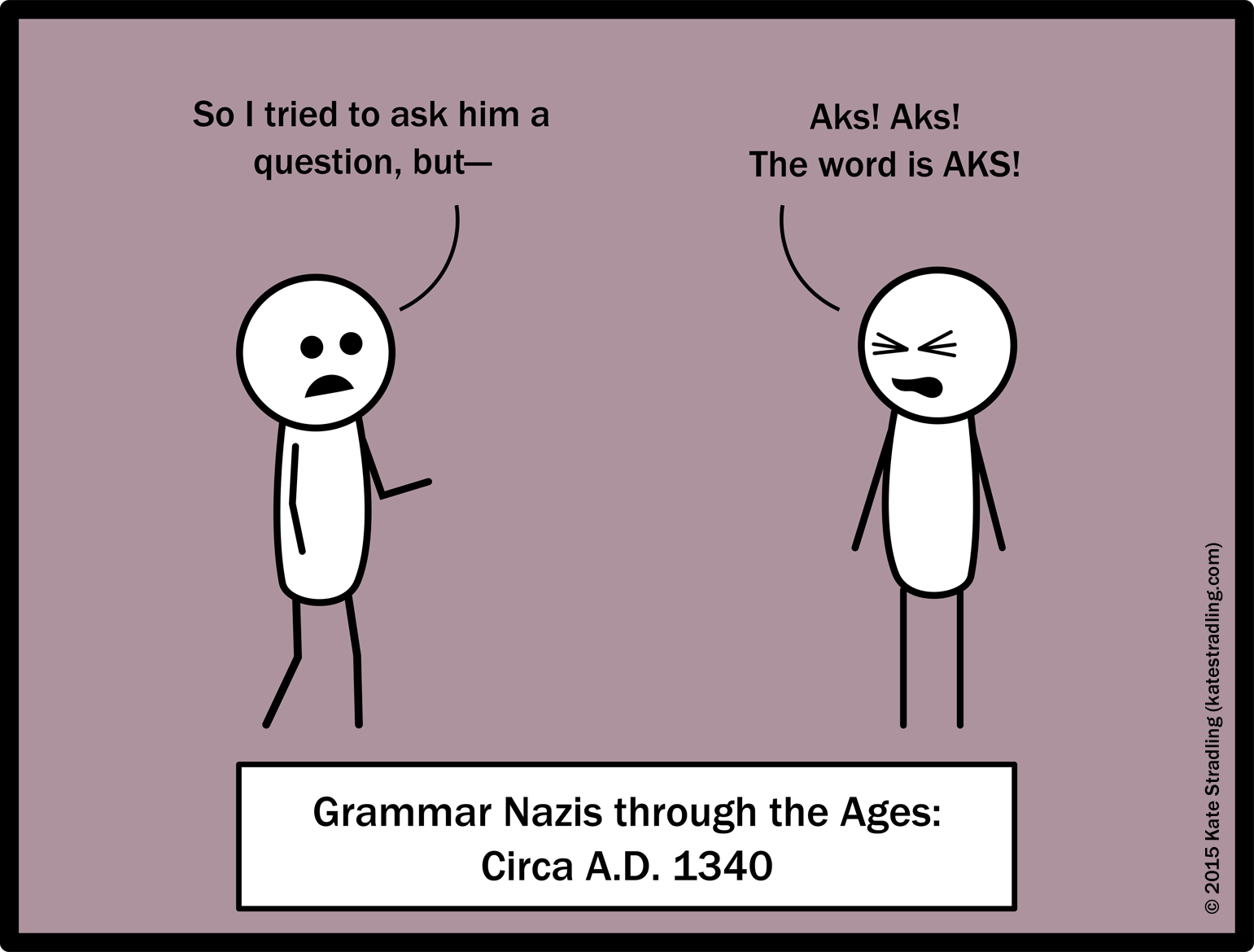

In other words, over the course of English history, it has not been at all uncommon to axe someone a question. In fact, for a good stretch in the Middle Ages, it appears to have been the standard.

Tell this to a modern Grammar Nazi, though, and you’re taking your life into your hands. (I did once. All I got in return was a hard stare and a single word: “NO.” I still get the giggles thinking about it.)

When two sounds in a word switch places, it’s called metathesis. This is a natural linguistic phenomenon. It’s the reason people sometimes pronounce prescribe as “perscribe” or nuclear as “nu-kyu-lar.” And, oddly enough, it probably has less to do with the speaker’s education and more to do with the ever mysterious brain-to-mouth process.

Nuclear is a fun one to look at. One of my professors back in the day pointed out that there are only, like, three words in the English language that end in that particular sound combination (the two-syllable “KLEE-er” as opposed to a one-syllable “KLEER” or “KLIR”), and that the other two are obscure. (I still don’t know what they are, so I can’t tell if he was being hyperbolic or literal; I can only report the anecdote.)

Meanwhile, you have particular, molecular, ocular, circular, spectacular, and dozens upon dozens of others than end in –cular: a quick Google search yields a list of 105, many of which have the scientific/medical context that someone might associate with nuclear.

In that respect, metathesis to “nu-kyu-lar” doesn’t seem so far-fetched. The sound cluster is a common linguistic pattern. (And this professor was a pioneer for Analogical Modeling, so patterns played a huge part of his research.)

Similarly, pronouncing ask as “ax” isn’t such a stretch either. The consonant cluster “sk” occurs less frequently than “ks”—so much so that we have a single letter in our alphabet that can represent the second cluster (much love to you, letter x), while the first is always two letters or more. Plus, “sk” requires slightly more effort to articulate.

Go on. Say the two sounds against one another.

sk-sk-sk-sk

ks-ks-ks-ks

I’m not going to say that people are linguistically lazy, but we all slur letters and drop syllables. I mean, really. Who’s vocab’s perf? Obvi erryone’s had this awks convo wi’ th’r fams, amirite?

The Path of Least Linguistic Resistance is almost a birthright, and metathesis is one of its many variables. If chronic mispronunciation really is a brain-to-mouth process issue, calling someone out for it would be akin to mocking someone who has a speech impediment.

But whatevs. Do what you want.

(Just remember, though: on the Grand Scale of Time, you might be the one who’s saying things wrong. Language change is funny like that.)