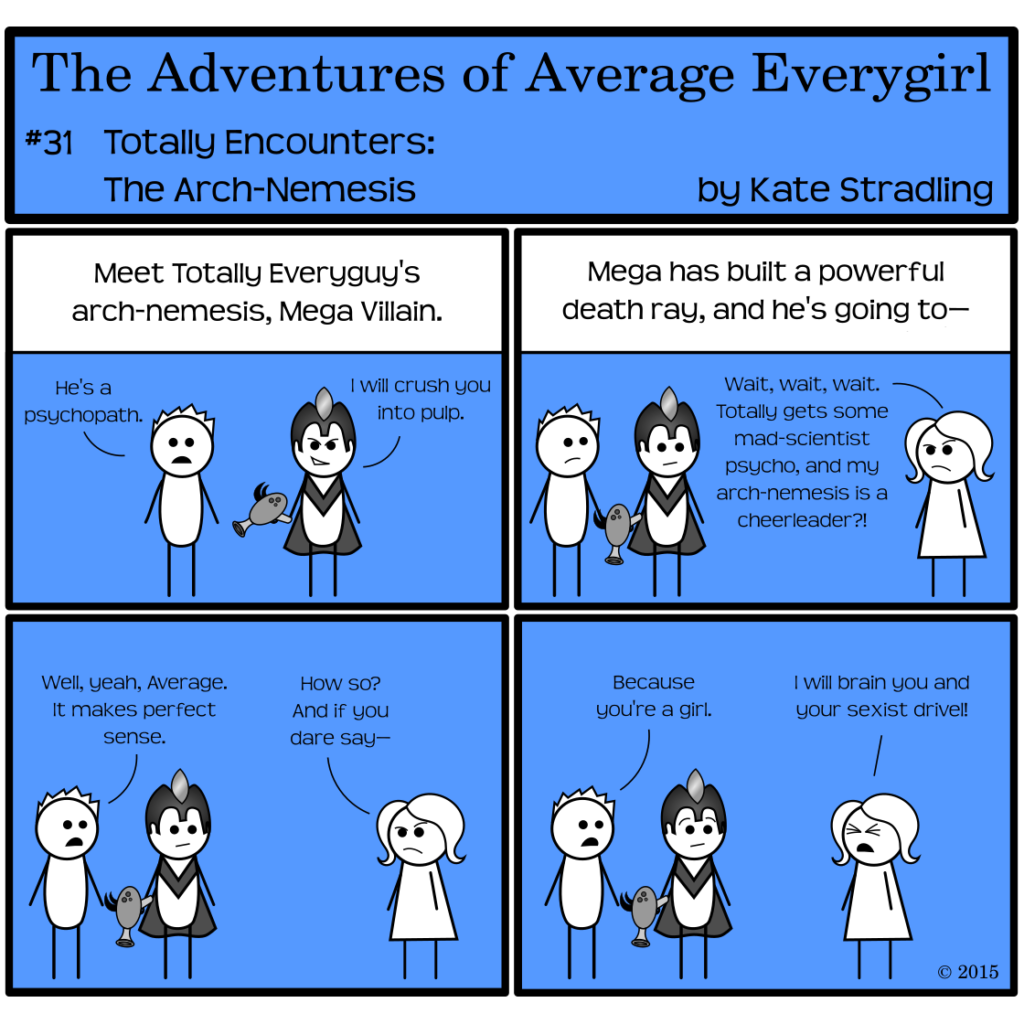

Let’s talk about sexism in literature, shall we?

*cracks open ginormous Can O’Worms*

When was the last time we had a series about a brave, courageous heroine facing a juggernaut of a villain? …that wasn’t in the “Thriller” category? …and where the heroine was not referred to as “gutsy” or “feisty” in any of the promotional copy/interviews?

(As an aside, I’m not really sure why the Thriller genre allows for women to take leading roles against heinous bad guys, but I suspect that it makes for higher drama, of the “Ooh, look! She’s part of the more delicate sex, so her chances of success are even lower than if she were a man” variety. Which is sexist. But I’ll give the genre kudos for letting women take the lead anyway.)

Now, for those series that do have a brave, courageous heroine facing a juggernaut of a villain, cross out all the stories that frame a romantic pairing or love triangle as equally as important a conflict.

Hmm.

Sadly, I’m drawing a blank here.

Sexism Baked into the Plot

There’s an unspoken line between what’s okay for heroines versus heroes. Heroines, for example, do not get a story that starts when they’re 11 years old and progresses through the next seven years of their life, to culminate in them defeating a genocidal maniac. But seriously, how cool would something like Hattie Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone have been?

(And yes, I’m using the British “Philosopher’s Stone,” because we all know that American publishers would have gone back and said, “Hey, we’re changing the name of the book… and your heroine’s a dude now because that sells better.” Sexism runs deep in the States. I’m at least giving the British publishers the benefit of the doubt. /cynicism)

Far from the elusive 11-years-old starting point, most of the “strong heroine” books I can think of start with a heroine in the 14- to 16-years-old range. And we all know why.

“Oooooooh! Who’s her love interest?”

A Feminine Coming-of-age

When I think “Bildungsromans with girls,” I think of Anne of Green Gables, Pollyanna, and other such fare. Domestic plots, easily won-over “villains,” muted love possibilities that will grow through sequels as the heroine gets old enough to be paired off, and so forth. These are wonderful books, but they’re also very tame.

Where’s the adventure for a female protagonist? Are there fantasy Bildungsromans that feature girls? Yes, they exist. They maybe don’t get as much attention as boy-as-main-character books do, and there are often some weird dynamics that wouldn’t necessarily work if genders were swapped. Like girls growing up to marry centuries-old fairy-types.

(Boys growing up to marry centuries-old fairy-types kind of gets the side-eye from society, don’cha know? But I cringe a little when either gender marries a centuries-old fairy-type, to be honest. Can you imagine the culture shock in that marriage?)

This is a conundrum I’m still kind of muddling through. I have a rule that if someone sees a gap in the spectrum of literature, it’s that someone’s responsibility to fill it. This allows me to fob off other people’s writing projects—(what’s with the whole, “Oh, you’re a writer? I have a book idea that you should write for me” mentality, anyway?)—but at the same time, looking at all the projects on my plate, I’m not so sure I can take up this banner against narrative sexism at the moment.

(Which means, of course, that I’m already fiddling around with it in the back of my head.)

I’m at least happy to start the conversation. What values do we place on our heroines vs. our heroes? What restrictions? And why do we do it?

“Why” is the most important question of all. It always points to truth, if you dig deep enough.

(Thank you, Socrates.)