I love ambiguous characters. Ulterior motives; subtle, between-the-lines manipulations; information withheld for strategic purposes. I love characters who know more than they’re saying and who use that higher knowledge for personal advantage. And I especially love the confidence required to allow other characters to think the worst of them in their pursuit of their greater goals.

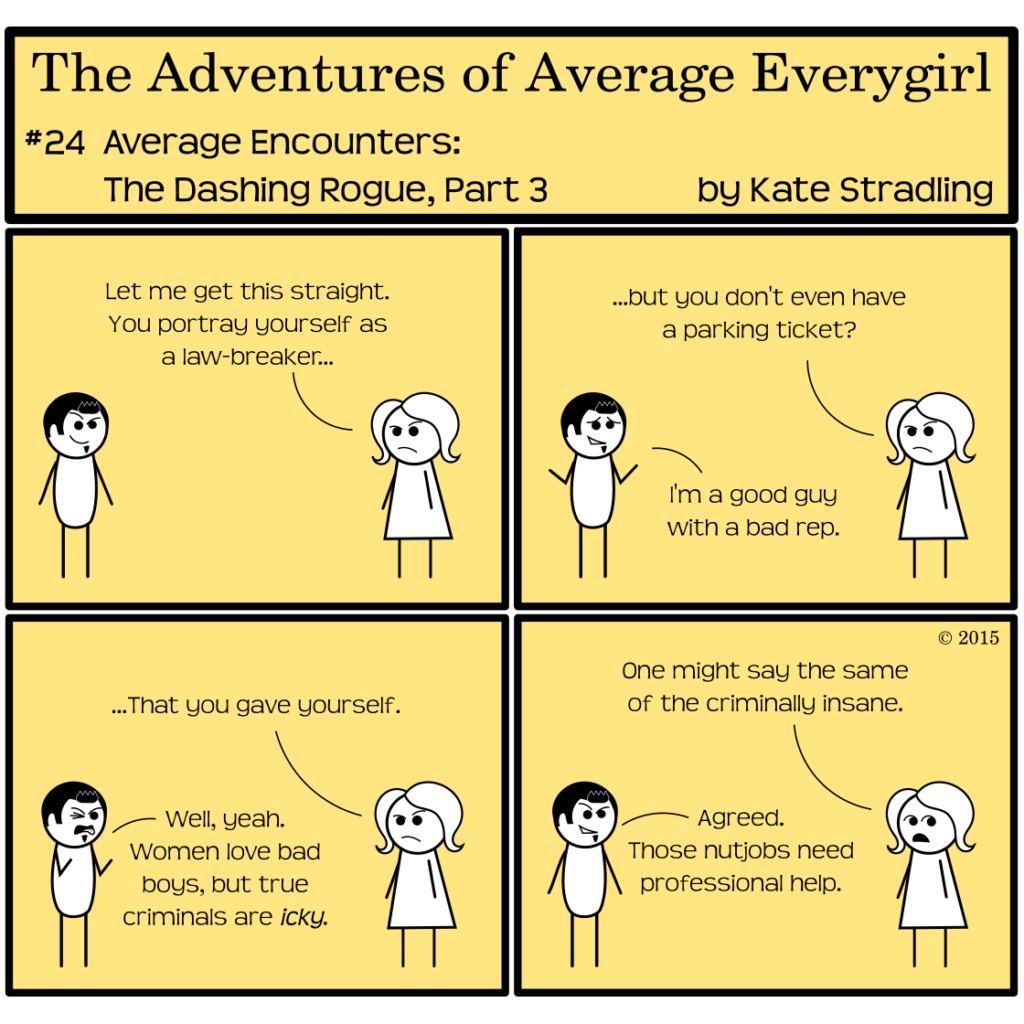

I do not, however, love when an author nullifies the Dashing Rogue’s bad behavior with an end-of-the-story LOL, jk.

“LOL. Just kidding about all that bad stuff I said I did. I’m really good and kind and so pure I should be bottled as a drinking water.”

Blarg.

Dashing Rogues and Redemption

One of the best things about reading a novel is watching the characters learn and change and grow. This is particularly true when a flawed character achieves enlightenment and mends their ways for the better. Redemption is a powerful theme, possibly one of the most powerful themes that exists.

And the plot twist of, “Oh, I was never really that bad—I just let people think I was” can rob that redemptive angle of its power.

If poorly done, instead of a resolution it becomes an excuse. The author pulls a punch instead of hitting the reader full force, figuratively speaking. And most readers, whether they admit it or not, want the punch in the face.

If a character has a shady past, it’s okay for them to own their behavior, to acknowledge it. “‘Twas I, but ’tis not I,” says Oliver in Shakespeare’s As You Like It. “I do not shame to tell you what I was, since my conversion so sweetly tastes, being the thing I am” (Act IV, Scene iii).

Reformation of character is a thing of beauty.

Admitting wrongdoing with a determination to be better requires internal strength and maturity. The dashing rogue or reprobate who reforms is a delight.

The “dashing rogue” with a manufactured shady past can be equally delightful, as long as the fabrication has occurred for a solid reason. A revelation of sainthood can backfire, however, particularly if the only reason for the roguish behavior was to create romantic conflict/tension throughout the story.

“Ooh! You’re so bad! I don’t want anything to do with you!”

“Baby, you want me! You know you do!”

“But you’re so bad! Why am I so attracted to you?”

“Because I’m hot and seductive. We should make out.”

“I cannot fight my attraction any longer! I must accept your criminal ways!”

“LOL, jk. I’m a teddy bear who donates all his extra money to orphans and runs a safe house for abused puppies. And I love commitment. Let’s get married right now.”

“Yay!”

Boo, I say. Boo.

If the only reason a character is a rogue is for the romance of it, and especially if his roguishness gets whitewashed in the story’s resolution, shame on that author. You can’t have your cake and eat it too. Choice and consequence must be as apparent in fiction as they are in real life.

Otherwise, really, what’s the point?

“Mindless escapism, Kate,” says the peanut gallery. “Duh.”

I disagree. So-called escapism that flouts natural patterns of behavior is no escapism at all. It’s an exercise in frustration at best, and an excellent reason for throwing a book across the room and never picking it back up again.