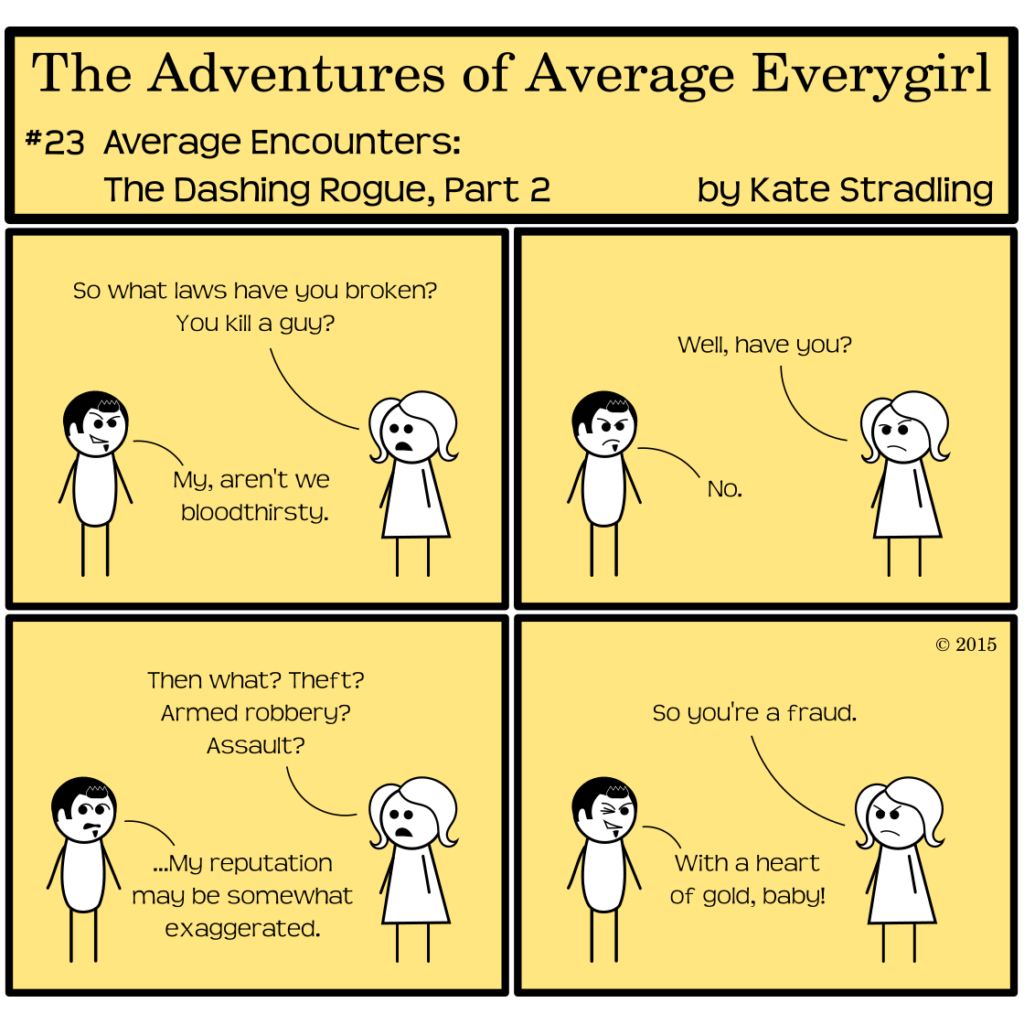

Confession: I instinctively want literary bad boys to be bad. If you go to the trouble of giving a character a horrible reputation, he should merit that reputation in some way. None of this watered-down sop of a conflict resolution: “See, he’s a rogue, but he’s not really bad. He’s just… misunderstood.”

That rationale is how we end up with highwaymen who don’t rob, pirates who don’t plunder, philanderers who don’t womanize, cat burglars who never steal anything, et cetera.

It’s one thing for a character to have a moral compass and quite another for him to use that moral compass to bewildering and incongruent effects. Every class or caste has its rules. Highwaymen rob travelers and shoot the ones who fight back. Pirates plunder and sink ships—it’s their occupation, so if they don’t do it, they’re no longer pirates, see? Philanderers keep mistresses and bounce from one woman to another. Cat burglars scope out art or jewelry collections and lift valuable pieces to hawk on the black market.

Anyone joining any these ranks has to accept that, “Yes, I’m going to do these unavoidable things, because this is the path I’ve chosen for my life.”

And, usually, their moral compass matches that choice.

Reputation matters

I will point your attention now to Exhibit A: The Princess Bride by William Goldman.

Everyone loves Wesley. He’s handsome and hard-working and loyal, and he absolutely adores Buttercup to a comical fault. He also masquerades as the Dread Pirate Roberts for two years—the Dread Pirate Roberts, “who never leaves survivors” (Goldman, p. 58)—with no detriment whatsoever to Roberts’s ferocious reputation during that time period.

I.e., the much-adored Wesley is a bloodthirsty killer when he’s on the high seas. Of his transition into piracy, he says simply,

“[Roberts] agreed to let me assist him in the next few captures and see how I liked it. Which I did.”

(Goldman, p. 183, emphasis added)

There’s no apology offered for his behavior. He doesn’t show any remorse. What’s more, no one expects him to. He is the quintessential Dashing Rogue, and to apologize for his path to wealth would undermine his character, who was willing to do anything and everything in his power to merit Buttercup’s love. Including turning pirate to amass a fortune for her.

Which is the exact opposite of so many diluted Rogues that plague literature. “I’m a pirate, yes, but I nobly spare my victims like no logical pirate would, because resources are scarce at sea and we can’t go wasting them on prisoners.”

Pulling punches to no effect

I think sometimes the author tries to soften a Rogue to make him more palatable to the reader. This treatment, though, can have the unintended side effect of rendering him into flavorless pap. There’s plenty of room for the “misunderstood” hero, but when the build-up makes him out to be a monster and he’s really a kitten in the end, I don’t feel relief. I feel cheated. If you’re writing a ruthless pirate, he had dang well better be chopping at people right and left, not prancing around spouting platitudes about nobly granting his enemies their lives and only killing in self-defense.

Unless he’s an inept pirate, I mean. But in that case he probably won’t last long. His enemies certainly aren’t going to extend him any courtesy.

(Unless they’re inept too, but then the whole story becomes inept unless its a parody or satire. None of these conventions apply if you’re writing parodies or satires.)

Long story short (“Too late!”): If you’re going to write the Dashing Rogue into one of your plots, embrace him in all his Dashing Rogue-ness. His moral compass is skewed to a different angle than society might allow, but that is part of his charm.

Citation: Goldman, W. (2000). The Princess Bride: S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure. New York: Random House

This is why, despite lacking certain moral standards, I really love Raymond Reddington from The Blacklist. He’s meant to be a bad boy (well, bad old dog, perhaps) and he IS. He has good motives for a lot that he does, but his moral compass is definitely not set to north. He kills, occasionally tortures, and consorts with other bad guys.

I won’t even get into the issue of Hannibal, because I’m still not certain how I feel about him (apart from feeling that he should be shot as expeditiously as possible).

Also he might find me and make a pie out of me, so….

I haven’t seen either show, but The Blacklist did look like it would have a satisfying anti-hero. Glad to hear it’s lived up to its hype. 😀

I can’t do anything with Hannibal. I internalize physical violence too easily, especially when it’s on-screen. (Unless you’re talking about Hannibal from the A-Team, because I do love it when a plan comes together. But that Hannibal wasn’t renowned for pie-making, that I recall, so… yeah.)

Sis is the same with physical violence. I’m fine with it, but NOT with torture. That gets me every time and makes me whimper softly for the next few hours and curl into a fetal position.

As for A-Team Hannibal, I DO love it when a plan comes together, but I love Howlin’ Mad circuses even better 😀 That is one show (along with Leverage and Hogan’s Heroes) that I can watch again and again.

Agreed 100%. What is it about perfectly mis-matched ensemble casts that makes them so delightful? 😀

Comments are closed.