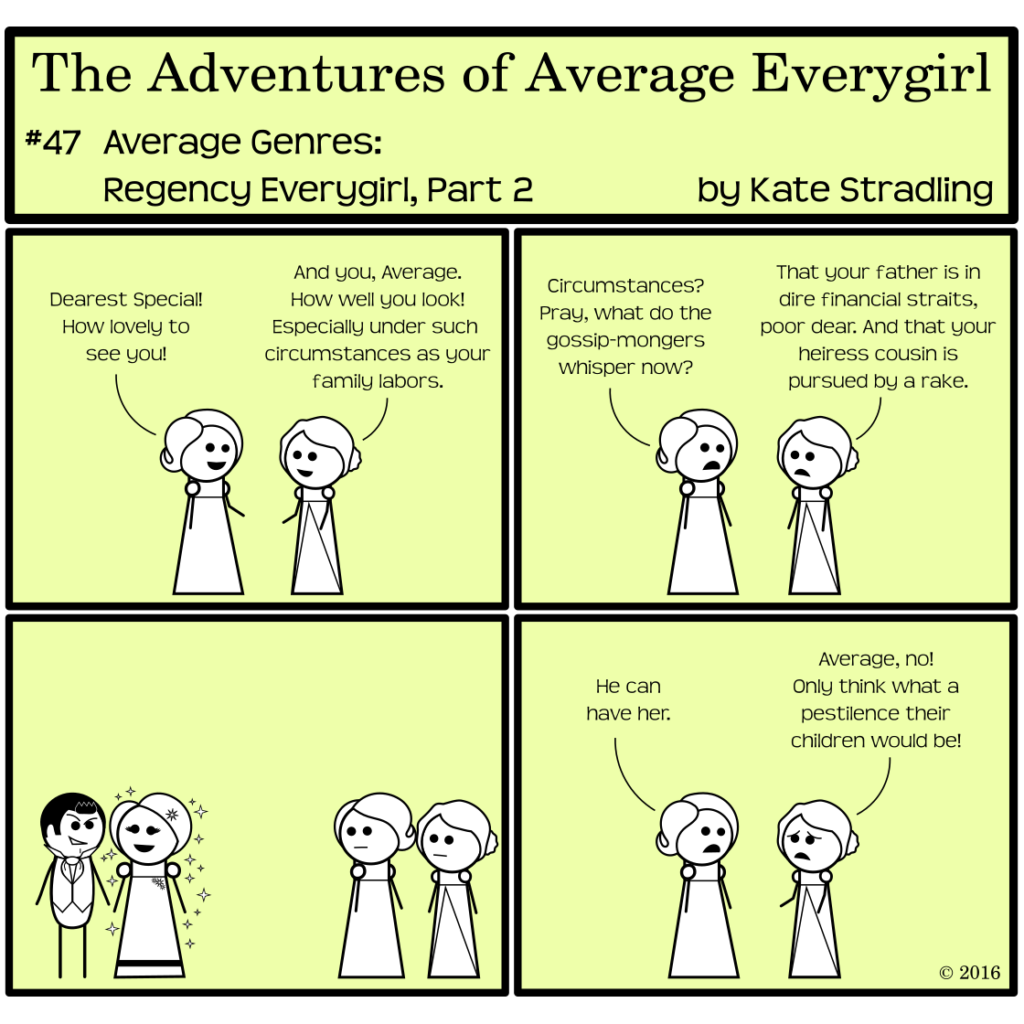

A number of literary tropes occur in the Regency genre, but I’m only going to hit on a couple of them in this post (as foreshadowed by today’s comic): the Family in Penury and the Heiress & the Rake.

Trope #1: The Family in Penury

Regency novels typically focus on the English upper class and nobility. Money in those ranks meant everything. This was an extravagant era led by an extravagant man. (Seriously, Prinny’s debts were astronomical enough that Parliament had to intervene, and yet he still continued his profligate lifestyle.) For much of the ton, excess luxury was treated as necessity. The upper classes had to be seen as living like upper classes. Men and women alike sought to marry into fortunes. Estates were mortgaged to the hilt to maintain lavish lifestyles.

A family in penury was a family in disgrace. Jane Austen’s social commentary confirms as much: we see it reflected in Sir Walter Elliot’s disgust at retrenchment, in Mrs. Bennett’s despair at her daughters’ lack of dowry, in the Dashwood family’s quiet retreat to the countryside, in Fanny Price being deemed little better than a servant, in the natural contempt that Emma Woodhouse displays towards Miss Bates, in how quickly General Tilney ejects Catherine Morland from his home.

Finances are a running motif of the era. Thus, when you pick up a Regency romance, you can pretty much bet that someone in those pages is penniless and desperate to hide and/or correct that detestable condition.

For Regency England, money equals status even when the ruling figurehead is hundreds of thousands of pounds in debt and racking up even more by the minute.

Trope #2: The Heiress and the Rake

The morals of this era were ridiculously lopsided. Upper class women adhered to a strict, virginal code of conduct while men could choose a life of debauchery (following after Prinny’s debauched example, no doubt). There were rules, of course. Mistresses came from the middle or lower classes, often selected from the caste of actresses and dancing girls that entertained the elite in more ways than one, and the men who kept them earned reputations as rakes. Such reputations did not get them shunned from good society, though. (In contrast, a woman’s reputation once tarnished was destroyed forever.)

Regency romance rakes have two settings: wealthy or poor.

If the rake is wealthy, his indulgences are excused; often he will reform for the heroine; sometimes the reputation is “exaggerated” (i.e., the author pulls their punch at the end of the book, à la “See? He’s actually a nice guy who let everyone think the worst of him!”).

If the rake is poor, however, he’s a scheming cad out to hoodwink an heiress into marrying him. Sometimes the protagonist is the heiress. Sometimes she’s the guardian of the heiress. At all times, those in the know agree that the prospective match is a deplorable mistake.

Keep in mind that as the reader you are supposed to love the first type of rake and despise the second. No, it doesn’t make sense, but it’s part of the rules.

The many, many rules.

This trope is a bit like the one where if a guy is a good looker, his stalking is romantic and exciting; while if he’s ugly, he’s just a creepy stalker and will probably try to kill the heroine before the end of the story.

On a (sorta) sidenote, one of my favourite regency period movies is Princess Caraboo, where the wealth and excesses are shown in a rather different light than usually shown. Instead of being glamorous and breathtaking, it’s seen in the light of debauchery and distaste.

I really love that film. Everyone should watch that film. Besides, it has Stephen Rea in it, and he’s really a darling.

Ooh, I LOVED Princess Caraboo! I haven’t seen it in ages, though. I need to track down a copy.

Heeheehee! I have all the BEST movies!

If you ever come to Australia, I’m going to kidnap you and make you watch ALL my favourites 😀

Awesome. Looking forward to it. 😀

I believe the quote from As Time Goes By is, “I always think that sounds like a village in Cornwall– Penury.)

I hadn’t thought of the poverty-disgrace connection before. But is it a outgrowth from the old Puritan concept of wealth as a sign of God’s Favor due to virtue, the so-called Gospel of Prosperity concept?

Love the waistcoat and cravat. He needs a cut-away coat, as well. 🙂

I wouldn’t even know where to begin for a cut-away coat. (Google images, I guess.)

I always assumed that the love of money explained the poverty-disgrace connection: those who had funds could buy their way out of whatever situations arose, and those who didn’t couldn’t. I like your Gospel of Prosperity theory, though. That one’s kind of built into the human psyche at this point.

Comments are closed.