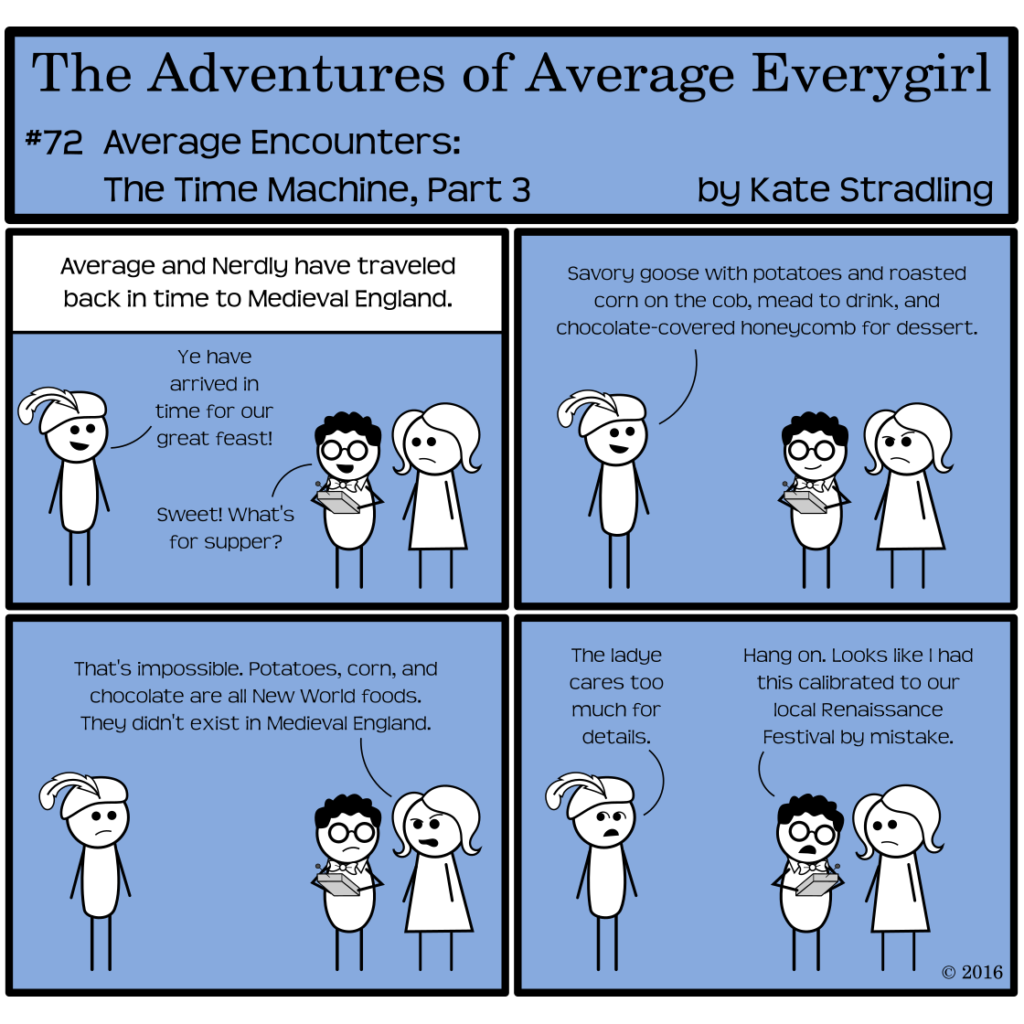

Anachronism, that bane of all historical fiction writers, can crop up when you least expect it. Obvious New World acquisitions—such as cocoa and tobacco—are easy enough to weed out. They are luxury items, associated with a certain lifestyle.

New World produce of a humbler nature might sneak into the narrative undetected. Basic as it may seem, those medieval peasants aren’t eating potatoes in their stew, and they can’t throw tomatoes at the prisoners in the stocks. Sorry.

A Curious Half-Anachronism

Corn provides a particularly interesting case, because the word existed in English prior to New World exploration. It referred generally to all grain rather than one specific type. Thus, in the KJV Bible, when Pharaoh dreams of seven ears of “corn,” it’s not the on-the-cob variety; and when Christ’s disciples pluck the corn from the corn fields, they naturally rub its chaff off between their hands before they eat it.

It’s easy enough, from a modern perspective, to substitute the narrowed definition of corn into either of these instances. For Americans at least, corn is almost everywhere we look, from our soft drinks to our gasoline. And because it’s so pervasive in our culture, it’s an effortless hop-skip-and-jump to assume that it’s always been there.

Alas, not so.

Anachronism, the Sloppy Uncle of Invention

Technology provides another source for potential anachronism. The introduction of gunpowder was a game-changer for any civilization. The development of cannons and guns rendered such protections as castle walls and plate armor ineffective where they had previously guarded against blades and battering rams. As guns increased in power, armor became a hindrance rather than a help.

The cycle of armor, too, has a logical progression to it. A prominent anachronism occurs in Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court: protagonist Hank Morgan encounters plate armor in 6th century England, roughly 700 years before it came into use. Mail—or maille, or mayle—preceded this more recognized type of armor. Oddly enough, the term “chain mail” is a later descriptor: Dictionary.com lists its entrance into the language as occurring between 1815-1825 (which exactly corresponds to when Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe artfully romanticized the Medieval period).

Which brings us to, perhaps, the most glaring anachronism of them all: the language itself.

An Ever-changing Tide

Language change can be at once both rapid and slow, obvious and subtle. Slang comes and goes like a flash in the pan, while a subject-agreement cycle might require centuries to manifest. Literacy plays a huge role in slowing change, but any encounter with foreign cultures will speed it up. All of these elements and more combine to make an ever-shifting linguistic field. Anachronism of terms, then, is basically impossible to avoid.

A Broken System?

Much has been written about the dysfunction of the English writing system. People lament that words like break and beak don’t rhyme, or that though, through, rough, trough, bought, and bough display six different pronunciations for the same cluster of four letters. Welcome to the Great Vowel Shift. In the 1300-1600s, English vowels migrated in their pronunciation.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, for people like me who love this sort of thing), this is the same time period in which Caxton brought the printing press across the Channel and standardized spelling became a thing. Mid-shift. Meaning half these vowels shifted their pronunciation after printers decided, “Hey, this is how that word is spelled.”

Haha. Oh well.

Personally, I adore the English spelling system. It’s quirky, yes, but all restricted codes are. Those who call for spelling reforms dismiss the history inherently tied to our lexicon. They also fail to acknowledge that funetik speling loox iliterit. English has 13 vowels and only 6 letters with which to represent them. A true spelling reform would require a revised alphabet.

Too much effort.

And of course, for any type of historical fiction, modern spelling applies. But if you’re headed back to the Middle Ages, be aware that any modern words dating from that period had a markedly different pronunciation back then. Chances are, your time-traveling hero won’t recognize them right off the bat, especially when they’re ensconced amid the jargon of their day.

Really good stuff here, Kate! (I actually have a more expansive vocabulary than this, but it’s kind of late).

Thank you, Stephanie! 😀

Comments are closed.