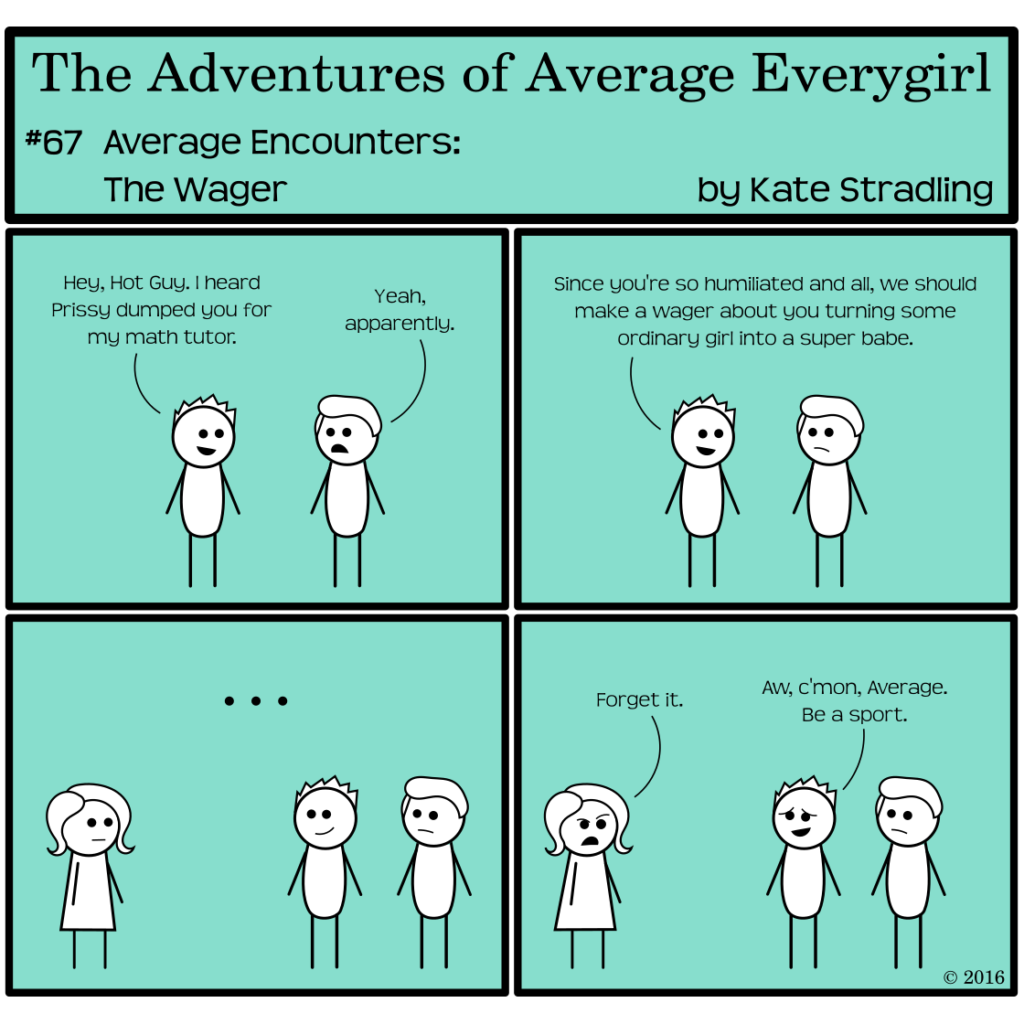

When it appears in literature and film, the Wager requires three main elements: Person A, whose reputation is on the line, Person B who challenges Person A with a bet, and Person C whom Person A must manipulate to win the bet.

And there’s this unspoken rule that somewhere along the line, Person A is supposed to develop compunction for using Person C as though they’re an object rather than a human. And often Person A falls in love with Person C and must make penance for using them in a bet. Also, usually, Person B tries to act as a spoiler by revealing the nature of the bet, because B secretly resents A and doesn’t want them to succeed or be happy.

But that’s not always the way it goes.

Classic Wager for the Win

The Wager motif is probably best recognized in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Henry Higgins bets Colonel Pickering that he can transform flower girl Eliza Doolittle into an elegant lady. To win, he must pass her off as authentic in a high-society crowd.

Shaw drew his inspiration (and his title) from a well-known myth found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Pygmalion, a master-sculptor of Cyprus, carves a woman from ivory and subsequently falls in love with her image. After supplication and sacrifice at the temple of Venus, he returns home to find the statue brought to life. They marry and live happily ever after.

Higgins and Eliza don’t end up together, despite what that ambiguous ending in My Fair Lady may have implied. Shaw felt that this would undermine Eliza’s character, to have her put herself under Higgins’s control again after gaining her independence. Instead, in his end notes, he has her marrying Freddy and running a flower shop.

Because it’s so much better for her to have a useless husband than an ungrateful one.

Apparently, he met with opposition from theater and film directors on the subject for ever after—to say nothing of his audience and his critics, most of whom would have preferred the happy ending of Eliza + Higgins = Lurve over the empowering ending of Eliza + Independence = Happiness.

But I digress.

The Wager aspect of Pygmalion, despite its iconic status insofar as literary wagers are concerned, fails to include any of the unspoken rules I listed above. Higgins does not regret using Eliza; he might fall in love with her, but he’s too proud to admit it, so it doesn’t matter; and Pickering genuinely wishes him well rather than trying to undermine him.

In fact, this Wager is probably the least offensive wager in all of literature and film. Yes, Eliza gets treated as an object and an afterthought, but she’s aware of the bet from the beginning. Her ultimate injury stems from her misguided assumption that she’s part of the club alongside Higgins and Pickering, that she’s an equal player in their antics. When, after her diligent work and incredible success, they can only congratulate one another as though she doesn’t exist, her rude awakening enables her to separate herself, take the skills she has learned, and live a better life.

The Wager itself doesn’t diminish her. What’s more, Higgins might win his bet, but he loses Eliza in the process. Adaptations of this story, so intent upon getting their “happy ending,” fail to capture this subtle nuance. Or perhaps they’re looking further back, to the happy ending of Pygmalion‘s inspiration.

Which is not such a great inspiration after all.

As far as that original tale is concerned, there’s no bet at all. Pygmalion sculpts the beautiful figure because he thinks real women are disgusting. And his “love” for his creation is more akin to obsession. He caresses the statue, and he kisses it. He even brings it gifts and dresses it in clothes and drapes it with jewelry and lays it in his bed and sleeps with it.

Yeah. He thinks real women are gross, but he fetishizes an inanimate hunk of animal tusk. Classy guy right there.

Kind of makes a person wish Galatea* had given him the boot when she very first came to her senses. It also kind of makes a person appreciate Eliza’s awakening in comparison. Much as I love a happy ending, it can only truly happen when both sides of the couple are equal.

Otherwise the underlying vibe becomes Master-and-Slave, and that is a losing prospect every time.

*Fun Fact: Ovid never refers to the statue-turned-woman as Galatea. He doesn’t refer to her as anything, except “the ivory statue,” “the ivory maid,” etc. The myth gained popularity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, during which time “Galatea” became the most common name for her awakened form and the name that basically everyone associates with her now.

Good analysis Kate… and a good read in the bargain.

Thanks, Uncle Kerry! 🙂

Comments are closed.