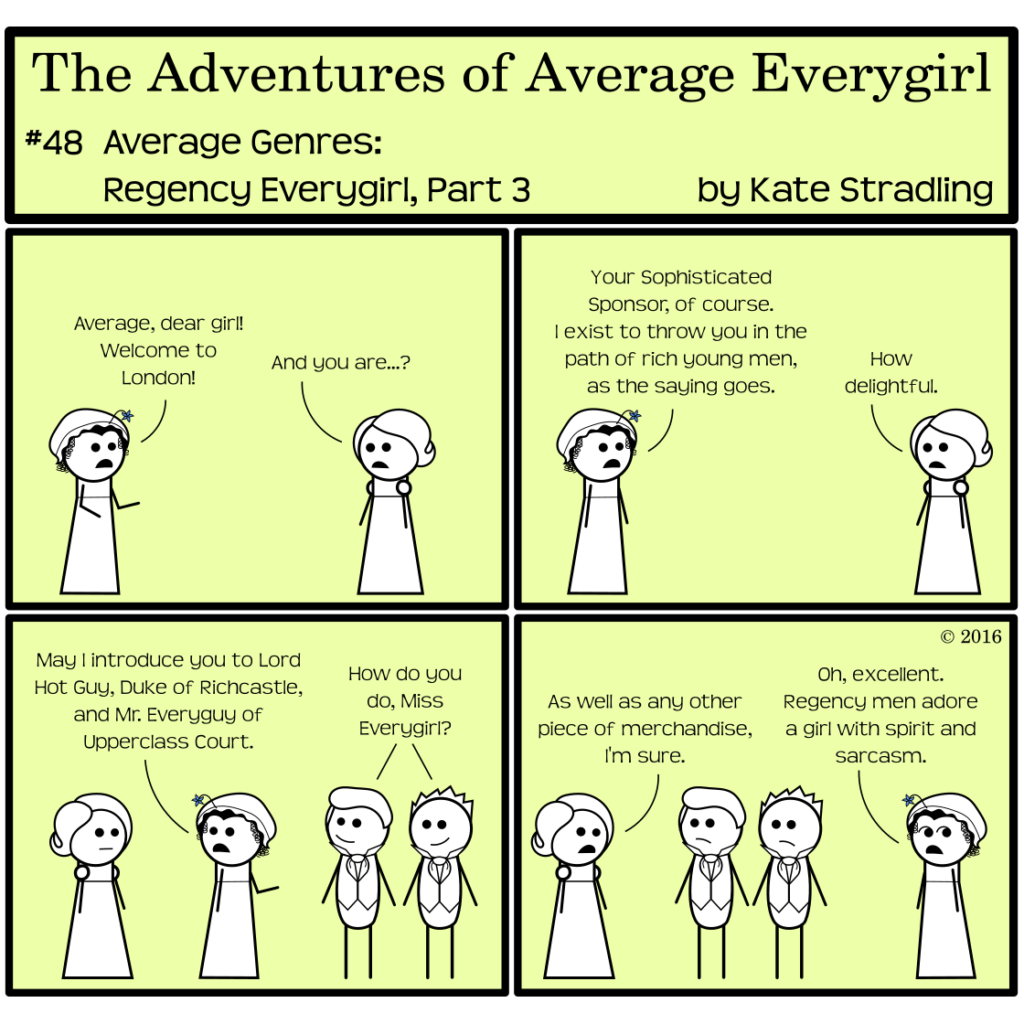

Amid the plethora of Regency social rules is the expectation that young ladies entering Society have an established friend or relative of high reputation to present them to gentlemen, et al. There’s no showing up to the party on your own here, girls. Any unchaperoned miss will be turned away at the door.

And then gossiped about for weeks afterwards, the hussy.

This wise female protector is only one gatekeeper that guards a lady’s path from the schoolroom to social success. Other established women will determine whether she remains in good standing, whether she has access to certain assembly rooms, and even whether she has permission to dance the waltz. (Such a scandalous dance, you know. Practically the Regency equivalent of twerking.)

And it’s all a great big joke, because the morals of this period were non-existent. The façade was all that mattered.

Gentlemen galore

The fictional dukes, earls, knights, counts, viscounts, etc. in Regency and other Georgian-era romances quite possibly outnumber the nonfictional noblemen from A.D. 1066 to present by now. A rich, handsome lord is the big fish when it comes to romantic heroes in this genre. This, even though the quintessential Regency-era hero was a mere “Mr.”

(Paging Fitzwilliam Darcy. You’re wanted by women everywhere.)

You can usually tell from the onset of the story which of the gentlemen is the romantic lead. If he’s handsome, titled, and possibly brooding, that’s your guy. The simple Mr. takes a back seat unless the Lord is distinctly unsuitable. Like old, or fat, or dull, or ugly, or married.

The fashion of the gentleman is another clue to his suitability. We can blame Beau Brummell for that one. Or thank him, as the case may be. This is an era where a bystander could tell a man’s tailor by the cut of his coat against his shoulders. Or so the Regency genre would have us believe. The fit of the coat gets mentioned an awful lot, along with whether or not the man’s Hessian boots are polished and how his cravat is tied. (Because apparently there are multiple variations for how to tie a cravat, and one receives greater status depending on how intricate and well executed the final result is.)

Variations on a theme

Variables to this Standard Regency Hero Template can be a breath of fresh air. Miles Calverleigh in Georgette Heyer’s Black Sheep, for example, doesn’t dress the part of a high-fashion gentleman because after two decades in India he doesn’t give a rip what Society thinks of him. His lack of fashion is as much a character trait for him as obsessive cravat-tying is for any other Regency hero, though.

Compare him to Julian St. John Audley, Earl of Worth from Heyer’s Regency Buck, who is a paragon of fashion without hardly trying. Worth carelessly makes up cravat styles that his fanboys immediately want to copy. He is not a dandy (heaven forbid!), but he gives such particular attention to his dress and grooming while projecting an air of indifference towards it because it’s fashionable to be fashionable while pretending not to care.

Calverleigh’s the better man in more ways than one, even if he is a mere Mr rather than a Lord. But they’re not in the same book vying for the same heroine, so it doesn’t matter.

Overdressed gentlemen, those dandies with their padded shoulders and multitude of seals and fobs, fall firmly into the “unsuitable” category. These are the uber-trendy characters, Regency hipsters perched on the cutting edge of fashion and executing it just a shade too severely for good taste. I’ve yet to read a Regency romance where an overdressed dandy plays the hero; they are typically an object of comic relief or outright scorn.