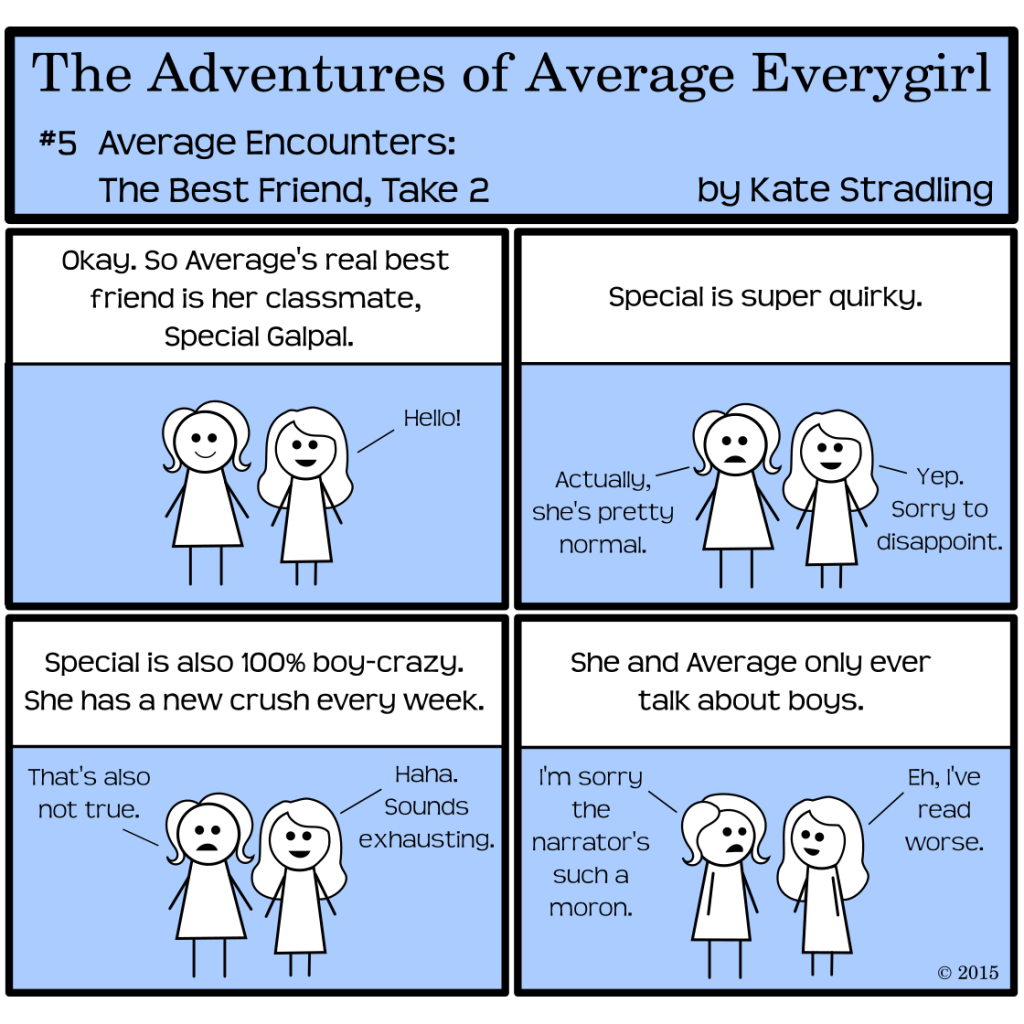

The quirky, boy-crazy best friend makes an appearance! Only for reality to squelch those made-up quirks!

I’ll admit, I had a boy-crazy friend once. She had a crush on N’Sync. Or the Backstreet Boys. Or… Menudo…? There may have been a specific boy-band member that she preferred, but I was never able to tell any of them apart, and she obviously wasn’t fanatical enough to make me learn. (I am, to this day, terrible at keeping up with trends in pop music, and I never understood the salivating hordes that followed those trends back in the day. I understand them now even less, but that’s because I’m wallowing in crotchety spinsterhood, or something.)

Brushing against reality

The boy-crazy best friend trope is realistic, to some extent, because giddy, giggly teen-aged girls have existed since the dawn of time. My issue with this trope in literature is that it gets magnified x 1000 of anything you find in nature. The delusional, boy-crazy character is often so deep into her delusions that the border has blurred and she can’t help but wander back and forth across it. And thus, she becomes a walking punchline.

Not necessarily a bad thing, but easily overdone and dangerously trite.

The last panel of this comic is, of course, a reference to the Bechdel test. I’ve never honestly performed this assessment for my own work, but I wouldn’t be surprised if a couple of my novels failed. And I’m okay with that. My goal is to create female characters who are smart, emotionally strong, and maybe a little ambiguous in their intentions. (Hahaha, I loves me some ambiguity.) If their conversations with one another happen to include mentions of male characters, it’s not because I framed their existence upon men. It’s because the male characters also figure into the plot. (Surprise!)

Excuses, excuses, I know.

Foibles and quirks in character-building

As I thought on my requirements for window characters, though, I realized that I do put them through a sort of test: basically, if they couldn’t stand as the protagonist of their own novel, of roughly the same genre or feel, they’re not worth their salt and probably need rethinking or better development. I apply this to other novels beyond my own as well.

I’d love to read the events of Pride & Prejudice from Jane’s point of view, for example. She has her own story line happening in the background, as real as any of Lizzie’s trials. Contrast her with Harriet from Emma: boy-crazy, focused on getting married, and possibly wouldn’t hold up as the protagonist of anything longer than a short story. I don’t hate Harriet, but I never really felt bad for her when Emma broke the news about Mr. Knightly. It was more like, “Pull it together, you dumb girl. He’s, what? The third guy you’ve fawned over in the span of a few months?” (Harriet is too easily persuadable, so perhaps I shouldn’t be so hard on her. I still wouldn’t want to read a book with her as the protagonist, though.)

And, of course, there are different levels of importance among the side characters. I think, above all, my primary inclinations for these relationships is this: birds of a feather flock together. If the main character is down-to-earth, chances are, she’s going to have a down-to-earth best friend. Quirks and gimmicks drive people apart, not because their friendship isn’t true but because the two friends end up walking different paths in life.

Or such is my observation.

This is a trope that contemporary young adult particularly is guilty of (tho I have to admit to two characters who are decidedly boy-crazy, so…. maybe I shouldn’t speak too loud :D)

I always felt sorry for Harriet. She’s so stupid she doesn’t know she’s stupid, which is just a waste. There’s a verse in Proverbs that says something like: “Why is there in the hand of a fool the purchase price of wisdom, since he has no heart for it” and that’s exactly how I feel about Harriet. She has so much stuff happen to her that could and should make her grow and mature (like Emma does throughout the book) and yet, she hasn’t the heart (mind) for it. All her trials and tribulations are of NO VALUE WHATSOEVER because she’s literally incapable of learning from them.

Then you contrast that with Emma….and suddenly the character of Harriet makes sense. Not as an entrancing or interesting character, but as she highlights the characters around her.

I’ve sort of gone off on a rabbit trail with this (sorry pardon :D) but it’s actually one of the things I really appreciate about Austen’s writing.

But then you’d have to decide on the merits of a character for character’s sake, and a character for the sake of other characters, and that’s a WHOLE OTHER can of worms 😀

Astute analysis, as always. As you say, Harriet is more of a foil to highlight Emma’s growth, and there’s certainly ample room for that sort of character in literature.

My real issue with this trope (which can be fairly true to life) is when it’s so over-stated that the character becomes a caricature instead. And I agree, it seems to happen most in contemporary YA. That doesn’t let the rest of us off the hook, though. 😀

Comments are closed.