(Did it work? Do I have your attention?)

Beowulf is one of those works of literature that, quite honestly, never interested me. Some beefy warrior kills a monster, and then he kills another one, and there’s a dragon in there somewhere, and at the end (spoiler alert!), he dies. I maintained a scornful disinterest for this epic over the course of a decade, until my conversion in my mid-twenties. Here’s how it went down.

Encounter #1

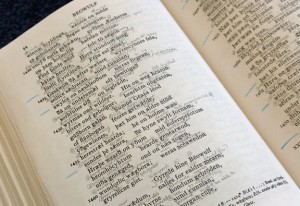

We read an excerpt in my junior year of high school. All I remember was a small picture of a bit of the actual text (which was completely unintelligible), a gruesome monster attacking in the dead of night, and that my English teacher had named her cat Grendel.

(As an aside, it is required for English teachers to name their pets after literary or mythical figures, right? Because they all seem to do it and think it’s pretty clever of them, says the girl who calls one of her cats Henry Pootel. That being said, Grendel really is a lovely name for a cat.)

I was in my Jane Austen Period at that point, and my major impression of Beowulf was that it was Not My Thing™.

Encounter #2

In my undergrad, for a History of English course, we got to work with an excerpt from the funeral scene of the poem for one of our projects. I learned the cadences of Old English poetry—alliteration and stresses and half-lines. I learned about wonderful kennings, like “bone-house” to mean the rib cage and “whale-road” for the sea.

But it was still, ultimately, a story about a beefy warrior who runs around killing things. And when I subsequently discovered that further Old English study fell in the realm of graduate-level classes, I skipped it in favor of a semester of Chaucer (who is delightful, of course). Middle English was at least semi-intelligible, and grossly entertaining to boot.

Encounter #3

Then came grad school. My fascination with historical linguistics (spurred mostly by the aforementioned History of English and Chaucer courses) prompted me to register for Intro to Old English in my first semester. I figured I could use a basic knowledge of the pre-1066 language, and that it would create a nice, fun diversion from Research Methods, Intro to Linguistics, and Pragmatics. It was my “leisure” course.

During the first week of class, I discovered that two semesters of Old English would fulfill my degree’s second language requirement, and thus spare me from sitting for a French exam. I also learned that the second semester involved translating Beowulf in its entirety.

That was almost a deal-breaker. Seriously, translating 3000+ lines about a beefy warrior killing things? But I really wasn’t keen to sit for the French exam, and as the semester progressed, my Old English study was coming in handy for my other classes. So I gritted my teeth and signed up.

I can tell you the moment, almost the very line, that I fell head-over-heels in love with this poem. It happened between 1420 – 1445, just after Beowulf and his group of men find Aescher’s decapitated head next to the swamp. (This seems romantic, right?) The group sits down on the sloping ground to mourn, and what follows is an otherworldly description of their surroundings: sea-snakes writhing in the water and serpents lying out on the ground, beasts fighting, and the call of a war horn. There was something in the passage, something that escaped translation, a glimpse of a time and place so foreign from my own that it swept me up.

That was the moment I looked through a window into another world, a world that no one in my time—be it author, artist, or filmmaker—could have possibly ever produced. It was the moment I recognized Beowulf as a work born from a violent past, where the unknown still smothered the human psyche. The fingerprints of distant generations were smudged all over it, and I was a literary tourist, just passing through.

What I love most about Beowulf is not the beefy hero (though there is much to love about him, says the reformed skeptic). It’s not the poetic elements (though they do fascinate). It’s that moment on the sloping hill by the swamp, and a thousand other untranslatable moments that followed. For me, the pendulum swung from indifference to adoration in almost an instant.

And I became a Beowulf snob.

I admit it. I’m a purist. You can’t truly love the poem unless you’ve read it in Old English, and you can’t do that without immersing yourself in the language. And if you’re reading this and think, “But I do love it, and I’ve never done any of that,” then I urge you to seek out the original text. Study it. Gloss it. Read it out loud. No translation can do it full justice, much as they try, because we cloud it with our modern fingerprints and dilute it with our modern moralities.

This from the person who disdained beefy warriors killing things. I’m sorry, Beowulf. I was utterly and completely wrong.

Last Words

Prior to my conversion, I was a skeptical translator, always removed from the action of the poem. There’s a point in the story (lines 946 – 949, to be exact) where King Hrothgar declares that he’s adopting Beowulf as his son to reward him for his bravery and heroism. I was sitting in my apartment, translating, and actually snorted. Immediately, in my skepticism, I asked, “And what if he doesn’t want to be your son? Does he get no say in the matter?”**

From that question sprang a plot bunny, and thus was born a story idea that took me another seven years to finish. “Literary Influences,” indeed. It’s on my docket to publish this year. That is news for another post, though.

(**He deflects it nicely, for those sitting on the edge of their seats.)

Can I just tell you how much I LOVE this? It explains a lot!! If I’m not careful, you’ll turn me into a Beowulf fan yet! Great post! Well-done!

Thanks, Stephanie!

I don’t know what happened to my other comment, but I wanted to be sure to make note of how awesome this post is. And say, for the record, that I officially miss out Sunday night walks. Like. Seriously.

Thanks, Shawnette. I totally miss our Sunday night walks. And the Thursday night walks. And just seeing you on a regular basis. 🙂

Pingback: Kate Stradling » My Swedish Grandmother Made Me Do It

Comments are closed.