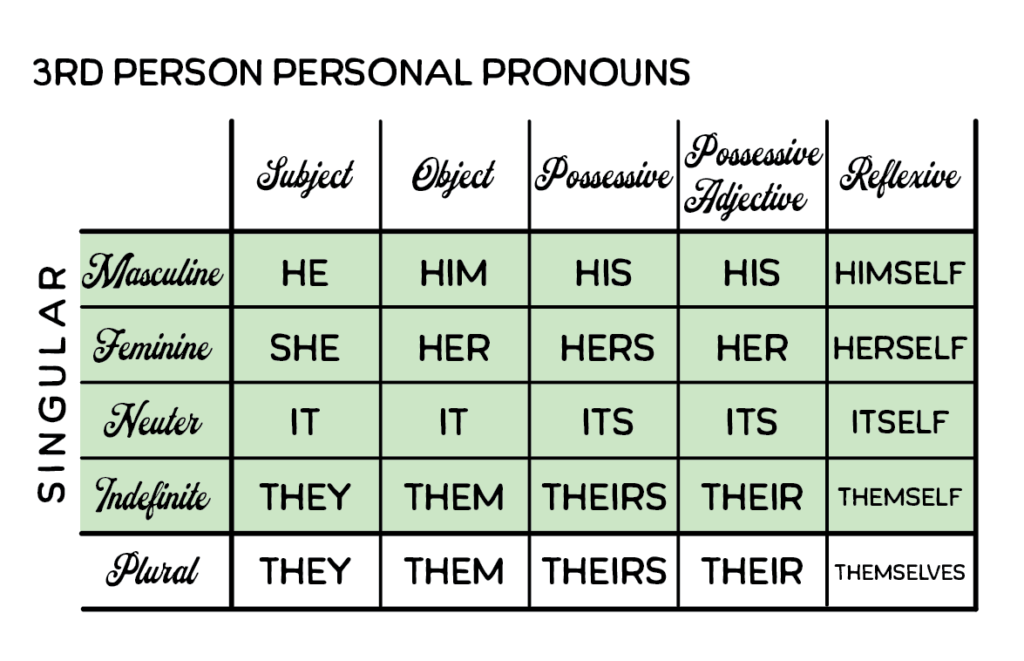

In Third Person Point of View, both Reader and Narrator exist outside the boundaries of the Story. The Narrator uses third person pronouns to recount character experiences and interactions within the plot.

Third Person Point of View is common in genre and literary fiction alike, a natural alternative to First Person. It provides a moving lens, able to shift with ease from character to character and scene to scene.

This POV is the most versatile of the three types, allowing a full spectrum of narrative intimacy to narrative distance, depending on which techniques the Author engages. (More on those in future posts.) This built-in versatility makes it an attractive choice for a wide array of stories, as long as the Author honors its boundaries and uses it wisely.

A Narrative Balancing Act

Because this POV uses only third person pronouns in its narration (not counting general “you” insertions in a colloquial style, or “I” insertions in an observational one), the Author must write with pronoun-referent clarity.

What does that mean?

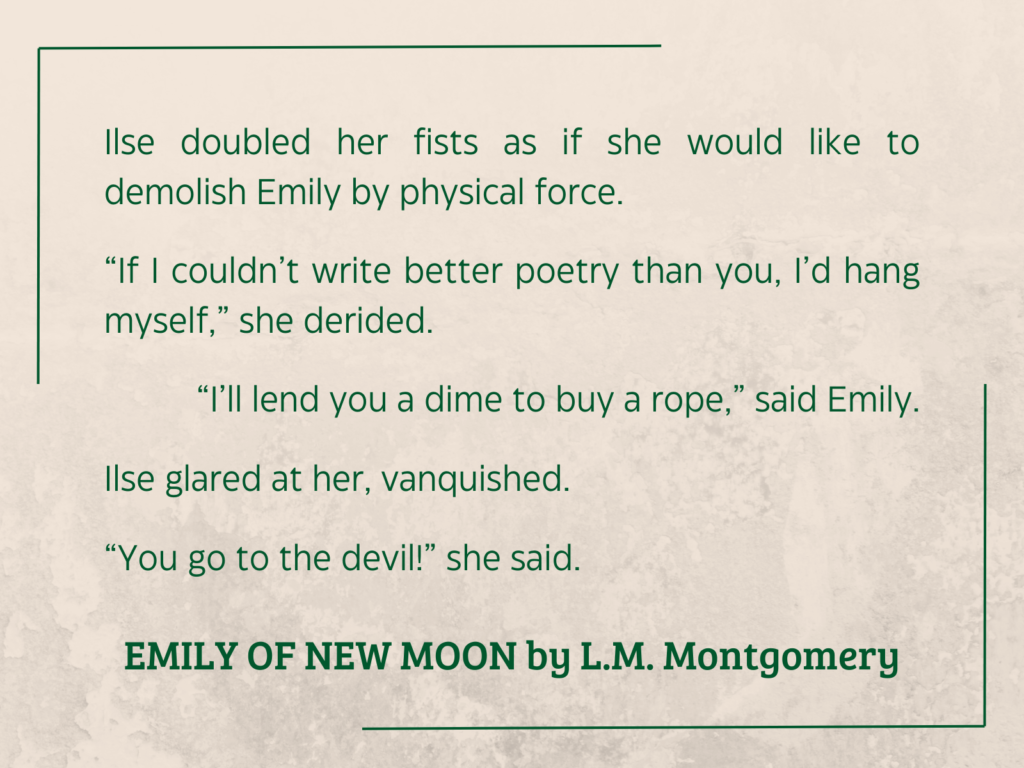

Plainly put, if two characters of the same gender are in a scene, the Reader should always know which character “he” or “she” refers to1.

While this might seem obvious, it also creates a situation where proper names appear on page more often than in first- or second-person POVs. Thus is born the balancing act:

- Pronouns themselves are ambiguous, deriving their meaning from context.

- Proper names are marked, becoming redundant if repeated too often.

- Both are Determiners, functional words that point the Reader to the correct character-in-action.

So here’s the guideline: in Third Person POV, a pronoun should always have a clear referent, and a proper name should appear only as often as absolutely needed.

(That’s about as prescriptive as I get. If you want to repeat your characters’ names more than necessary, feel free. It can make for clumsy Dick-and-Jane style reading, though.)

In addition to this balancing act, Third Person POV cozies up to some other narrative pitfalls. Let’s explore those, shall we?

#1: Head-hopping

Head-hopping occurs when the narrator jumps from one Viewpoint Character to another without a break—either chapter or scene—to cue the transfer. At worst, it results in a sloppy narrative, difficult for the Reader to follow.

It’s not necessarily wrong, though. Simply not on trend. When used with intention, it does not disrupt the story at all. Instead, it functions the same way a movie camera does, panning focus from one character to another as the plot requires.

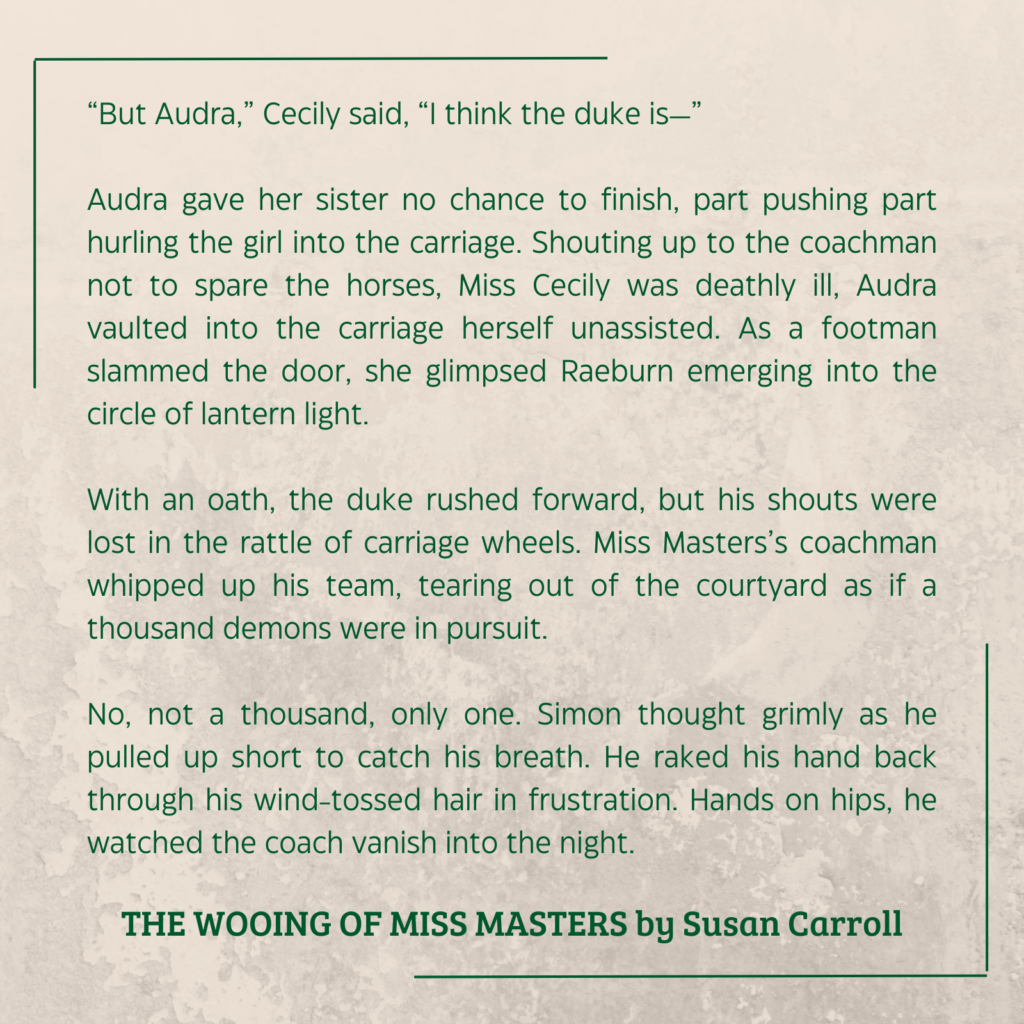

THE WOOING OF MISS MASTERS by Susan Carroll frequently shifts mid-scene from the heroine to the hero, allowing one to start in the chapter’s focal position and the other to end there. Carroll executes the transitions smoothly enough that the Reader might not even notice.

Whether you can get away with head-hopping often depends on the third person narrator’s degree of Omniscience, but that’s a discussion for another post. (Or two, as the case may be.) If you use it, just be careful not to give your Reader literary whiplash.

#2: Expositional info-dumping

Expositional info-dumping can happen in any of the three Points of View, but Third Person gives more opportunities. A narrator not directly connected to story events can insert world-building and backstory as they please. This ties into authentic storytelling, that we relate information not according to a linear timeline, but according to its emotional resonance.

Therefore, this pitfall occurs when the Author believes the Reader needs certain information to understand events and thus word-vomits that information onto the page instead of integrating it more naturally into the narrative.

These are the wall-o’-text descriptions of a room’s layout, a town’s history, a character’s background. Sometimes the info-dump serves as a reveal, clarifying motivations or off-page occurrences in a manner more succinct than a scene-by-scene depiction would supply.

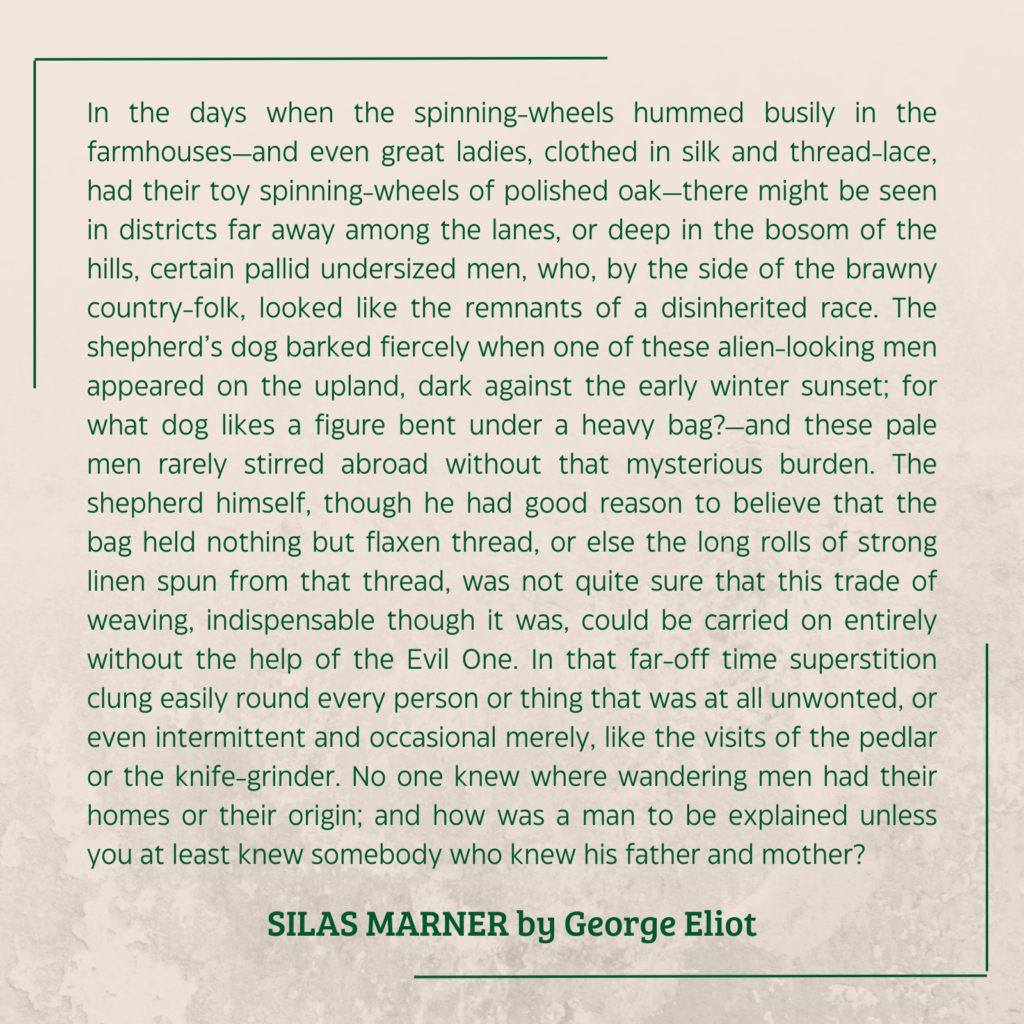

SILAS MARNER by George Eliot opens thus:

Be honest. Did you read the whole paragraph? (You didn’t, because that’s only half of it. It continues for another 200+ words of expositional magniloquence.)

Regardless, this opening sets the stage for the eponymous Silas, a misunderstood craftsman from a time long past. It establishes setting, tone, and reader expectations for the story yet to come.

And a modern critique group would rip it to shreds, whether justified or not.

#3: Narrative intrusion

Because the Third Person Narrator is not part of the story, any commentary they make reminds the Reader that they are reading a book. As a deliberate device, this can add to the tone. If done carelessly, though, it might repel your Reader instead of engaging them.

Consider this paragraph from Jane Austen’s PRIDE AND PREJUDICE:

The “I wish I could say” in this excerpt brings the narrator into frame when they have remained mostly invisible throughout the book. But it’s charming and on point for the tone in which Austen writes.

Classic novels get away with all of these POV pitfalls. Modern ones receive criticism. If you decide to head-hop or info-dump or allow your narrator to intrude with their own thoughts, be deliberate about it.

After all, it’s only wrong if you didn’t do it on purpose.

- What are your favorite 3rd Person POV stories?

- Where have you encountered a creative or unusual example of this POV?

- What draws you to (or repels you from) this POV?

Up next: Present Tense Narration

Previous: Second Person Point of View

Index Page: Point of View

- Except in cases of intentional pronoun ambiguity, but that’s a technique best used sparingly. ↩︎