When we encounter the term “worldbuilding,” instinct points us to the fantasy genre. All fiction requires worldbuilding in one form or another, though. In the realms of “Too Much Information,” we have a wonderful case study within the Regency sub-genre: Jane Austen vs. Georgette Heyer.

Austen lived and published during the Regency period. She wrote characters who lived in that setting for an audience who lived in that setting, a circumstance that gives her authenticity by default.

Roughly 120 years later, Heyer recreated the Regency setting for an audience who had no experience with it. She published the original Regency romance, Regency Buck, in 1935.

This novel contains All The Things.

Austen vs. Heyer

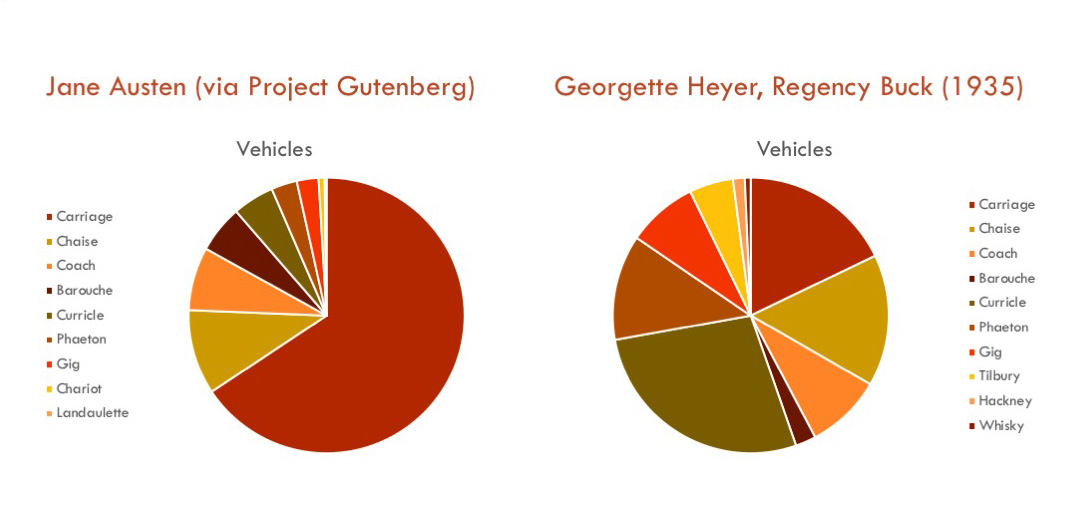

If you compare the language in Regency Buck to that of Jane Austen, many stark patterns emerge. We see the striking difference between Austen and Heyer in something as simple as their mentions of horse-drawn vehicles:

Austen’s generic terms (carriage, chaise, coach) account for 83% of her vehicle references. Heyer’s generic terms amount to only 42%.

My sample size included all six of Austen’s complete novels, plus Lady Susan and Love and Freindship. In all, I found 431 vehicle references: 283 carriage, 43 chaise, 32 coach, 24 barouche, 21 curricle, 13 phaeton, 11 gig, 3 chariot, 1 landaulette.

In contrast, Heyer’s Regency Buck (1935) has 291 vehicle references on its own, more than half of what Austen stretched out over 8 distinct works. And the breakdown: 80 curricle, 52 carriage, 45 chaise, 36 phaeton, 26 coach, 24 gig, 15 tilbury, 7 barouche, 4 hackney, 2 whisky.

All in a single novel.

Special Use

The comparison doesn’t end with mere numbers, though. Austen uses her specialized vehicles as a means of subtle characterization.

For example, the 7 references for “barouche” in Emma all refer to Mrs. Elton’s sister’s “barouche-landau.” If the term is not in Mrs. Elton’s dialogue, it’s either the narrator or Emma making a tongue-in-cheek reference to this carriage.

The barouche-landau never appears in the story, except in reference only. Austen uses it as a running joke to highlight how vulgar and pretentious Mrs. Elton is. The woman is trying to position herself as the most sophisticated person in the neighborhood. She believes that “things” prove her better worth, even when those things belong to her relatives and not herself.

Similar affectations emerge in Mary Musgrove’s jealous observation that her newlywed sister has a “very pretty landaulette,” and in John Thorpe’s ridiculous assertion that his gig is “curricle-hung.” Horse-drawn vehicles were a status symbol and a sign of wealth—or poverty, as the case may be. Austen uses them intuitively as such.

(For further detailed insight on this topic, see this lovely blog post. The writer goes far more in-depth than my analysis of Austen’s usage, but I was delighted to find my thesis held true.)

Now compare Heyer’s usage in Regency Buck. There’s no subtle characterization involved. Instead, the narrator slaps the reader with these specialized names and references over and over and over again: “Don’t. You. Know. We’re. In. A. Regency. Setting?”

Irrelevant Details

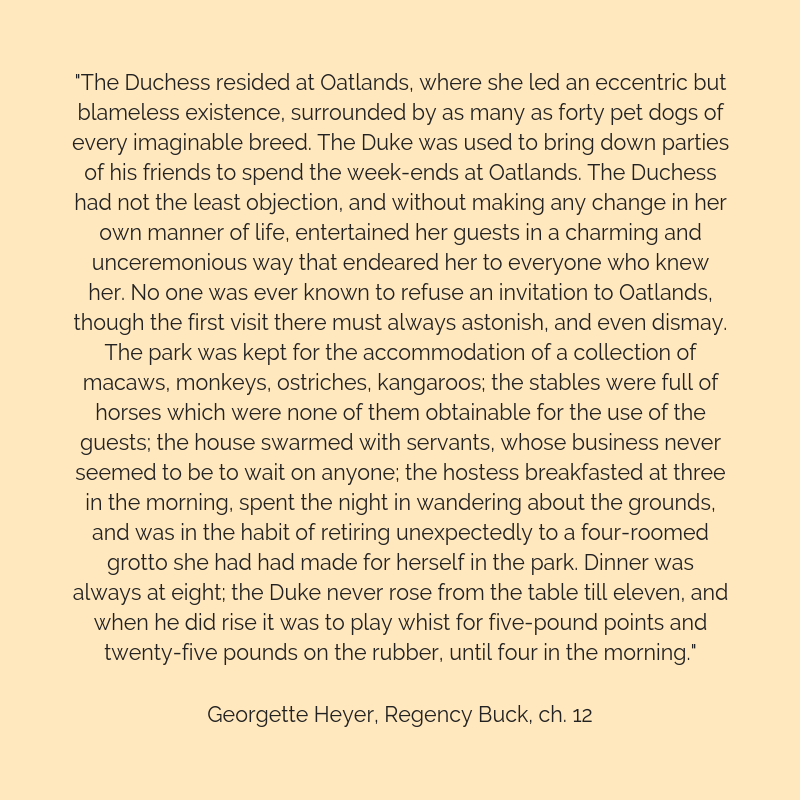

Regency Buck further offends our sensibilities with passages such as the following, about the Duchess of York:

Now don’t get me wrong. That paragraph is hilarious, and basically true. The Duchess was crazy-cakes and the Duke was a piece of work, and anyone who visited them had quite the spectacle to observe. But here’s the very next sentence:

“The Duke, who never saw his wife except at Oatlands, had naturally not brought her with him to Belvoir.”

Because Belvoir Castle is where the narrative actually is. The Regency Buck characters never travel to Oatlands, the Duchess of York never gets another mention, and the whole long description is, for any plot-minded reader, 100% skim-worthy, if not entirely skippable.

I can only imagine that Heyer came across this info in the course of her research and was like, “Oh, yeah. That’s going in the novel.” And while it was fine for a first draft, the book would be stronger without it and other similar asides.

ALL THE THINGS

Over the course of Regency Buck, Heyer name-drops 100+ historical people and 200 geographical points of interest. But not without anachronism. Among them,

- We meet “Princess Esterhazy” at Almack’s Assembly Rooms, in an 1811/1812 setting. Her real-life counterpart, Princess Maria Theresia of Thurn and Taxis, didn’t marry Prince Paul Anthony Esterházy of Galántha until June 1812. In Bavaria, no less.

- Countess Lieven is also present at Almack’s, but her real-life counterpart didn’t arrive in London until 1812 and wasn’t a patroness of Almack’s until 1814. (She also introduced the waltz there, so no waltz-dancing before then, I guess?)

- Thomas Cribb is manning his saloon, Cribb’s Parlour, within six months of his infamous prizefight against Tom Molyneaux. By all accounts I could find, the real Cribb tended bar for two other establishments before settling on the one that would take his name. He only started bartending after his retirement from the ring. Even if he could do all that within six months, Heyer frames Cribb’s Parlour as a well-established haunt for the male half of London.

So, in her haste to include a glut of Regency details, she undercuts her reliability.

But the over-information goes beyond an onslaught of place names and people. The plot includes detailed accounts of a prizefight, a cock fight, and a curricle race. There’s a duel, an attempted murder, more than you ever wanted to know about snuff, two kidnappings, and a grand reveal. The characters have a London season, a Brighton season, and two separate country manor house visits, one of which includes a Hunt.

Basically, if people in the Regency era could have participated in an activity, Regency Buck’s characters did it.

A Trailblazing Legacy

But then, Heyer couldn’t have known she was establishing a sub-genre of historical romance. She wrote an additional two dozen Regency novels over the next 30+ years, and her style tempered with her familiarity to the setting.

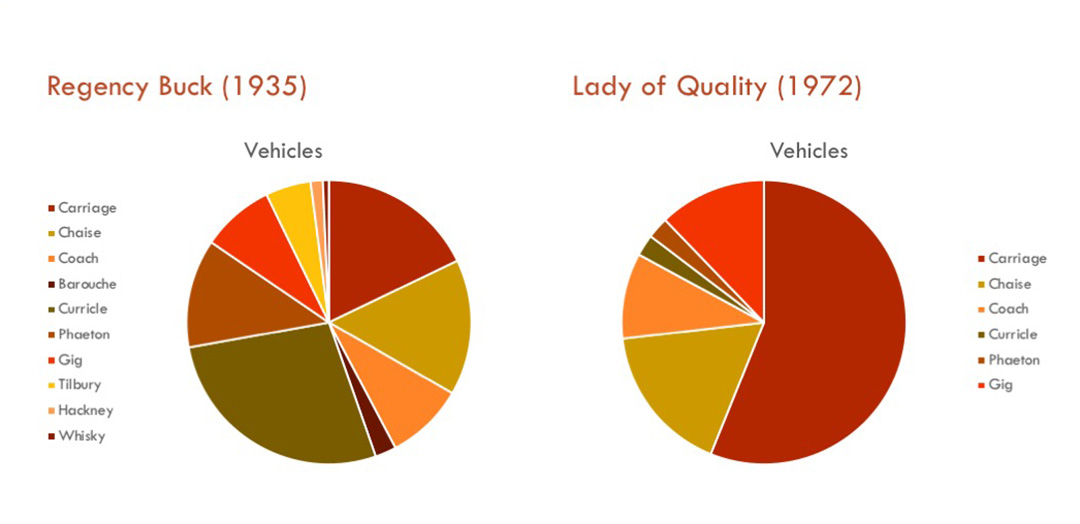

In fact, if you compare the mention of horse-drawn vehicles of her first Regency novel to her last (Lady of Quality, 1972), the contrast is startling.

Regency Buck (1935): 291 vehicle references (80 curricle, 52 carriage, 45 chaise, 36 phaeton, 26 coach, 24 gig, 15 tilbury, 7 barouche, 4 hackney, 2 whisky)

Lady of Quality (1972): 42 vehicle references (23 carriage, 7 chaise, 5 gig, 4 coach, 1 chair, 1 curricle, 1 phaeton)

As you can see, we’re back in Austen-esque ratios. In fact, the more generic “carriage, chaise, and coach” make up exactly 83% of the Lady of Quality pie.

Heyer will always be known for being wordy, but she learned from her mistakes with Regency Buck. And we can learn from them too. Less is more. Don’t undermine your narrative with too many details.

***

Up next: Barrier Objects: An Introduction

Previous: Too Much Information

Back to Liar, Liar Navigation Page

Wow. Now I need to go back and reconsider my world building and use of language. Thank you for sharing your insights to help the rest of us!

Balance is key. We want to give enough detail for a clear picture but not so much that the reader’s eyes glaze over. Thanks for reading and commenting. Happy writing!

Comments are closed.