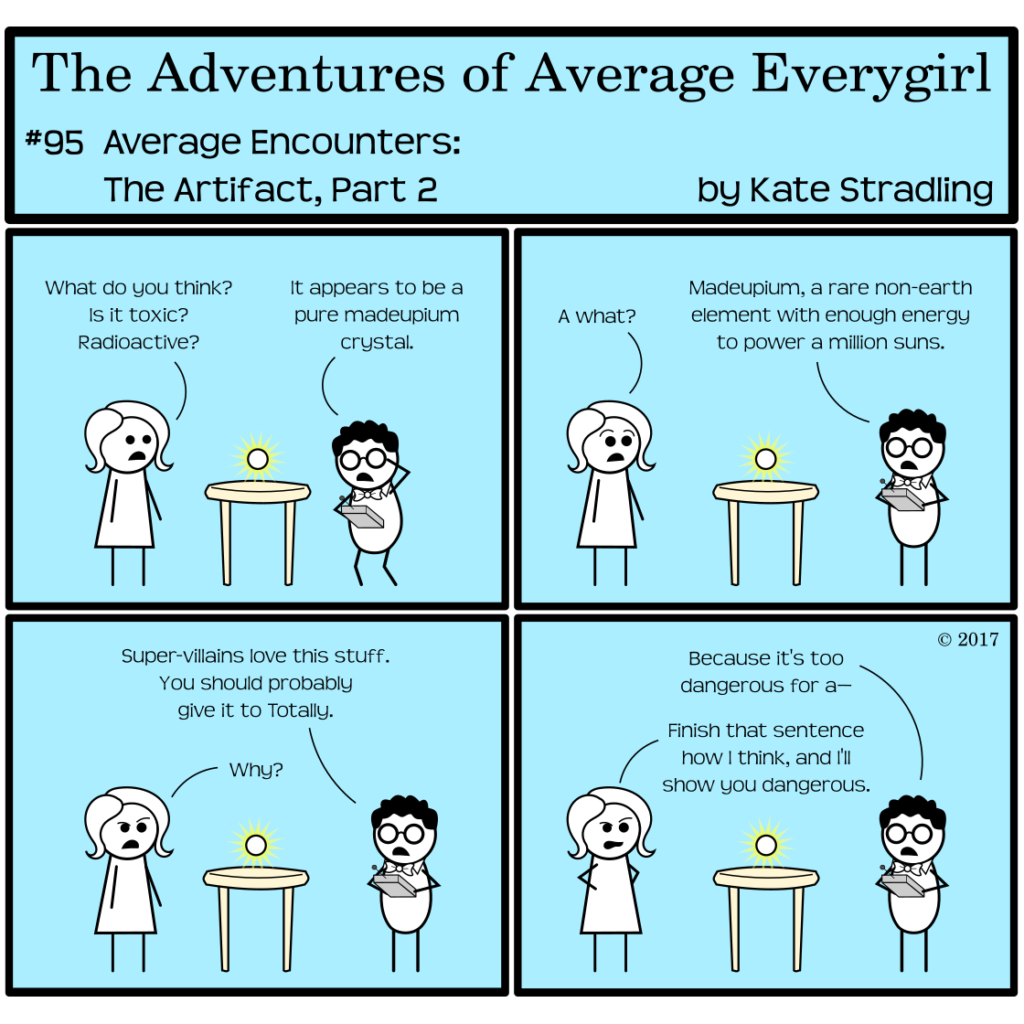

NOTE: In case anyone’s forgotten my generic characters’ names, “Totally” refers to “Totally Everyguy,” Average’s male counterpart. (I add this note because my own mother said, “Wait, who?” Hahaha. I’m sure he would do wonders with this latest plot element.)

The Science of a Good Plot Element

So, it’s been at least 15 years since I studied any of the natural sciences. I had CP Chem in high school and a semester of Physical Science in college that included a chemistry unit. I don’t remember a ton about them (because that was half a lifetime ago, y’know), but one thing that did impress me was the solid truth of the periodic table.

Like, “These are the elements, and because of how atoms work, these elements are set in stone.”

(We’re not getting into isotopes or any of that complicated stuff, m’kay?)

The result is that any time I come across a fictional work where characters utter something akin to “This is a non-earth element,” my BS detector pings off the chart.

Because, as far as I understand, the periodic table has defined every possible element in existence, with the exception of a handful of man-made elements appended at the end. And all of those are extremely unstable and thus unlikely to exist anywhere outside the laboratory in which they are (briefly) created.

Am I wrong? Maybe I’m wrong. If so, my apologies. (And please leave an explanation for why I’m wrong in the comments. References much appreciated.)

It’s Not “Just a Story”

The realms of fiction exist to take us beyond the natural world. Even so, they have to follow natural laws or else they destroy verisimilitude.

Verisimilitude: The semblance of truth. The term indicates the degree to which a work creates the appearance of the truth. (Harmon & Holman, A Handbook to Literature, p. 538)

This oh-so-useful term doesn’t apply only to realistic fiction. For me, it’s a defining feature that separates good writing from bad across the spectrum of literature. This “semblance of truth” allows us to slip into the story, to feel alongside the characters, to agonize over plot twists and rejoice at happily ever afters.

When it breaks, we jolt out of that fictional world, and we’re generally none too happy about it. (This ties back to the unspoken Author-Audience Contract. We want a story to fool us, but without verisimilitude, it can’t.)

Verisimilitude is a tricky beast. It allows the same person to accept Tolkien’s mithril wholesale while they give the squinty side-eye to Doc Brown’s flux capacitor. In the Star Wars franchise, it simultaneously invokes the adoration of millions and the scorn of physics teachers everywhere.

(Or maybe it was only my physics teacher. My class once got a lecture on the properties of outer space thanks to someone mentioning Star Wars.)

It is, in short, subjective according to an individual’s understanding of Truth.

Fantasy at an Advantage

When it comes to verisimilitude, the fantasy genre holds a distinct advantage: the reader comes to the story with their sense of realism already disengaged.

No one fact-checks J.K. Rowling on the existence of magic. Nor do they chide C. S. Lewis on the implausibility of an inter-dimentional portal at the back of a wardrobe. A plot element need not be anchored in reality to resonate truth. It need only resonate truth within its fictional domain.

Because fantasy storylines exist outside of the normal, explainable world, many patterns of truth fall instead to characters, relationships, and personal growth.

But this doesn’t let a fantasy writer off the hook when it comes to rules. If Harry Potter suddenly created a portal to another dimension by playing a song on a flute, for example, the reader would likely object. (The HP universe requires wands for working magic, and Harry’s more of a jock than a musician. Not that he couldn’t be both, but he isn’t.)

Those who write fantasy engage in a boatload of world-building for this very reason. If they skip this step and change rules to accommodate their plot, they’ll undermine the story’s verisimilitude.

And this goes double for the author who writes in a “real world” setting. If that’s your bread and butter, beware the errant plot element.

Ultimately, you see, all fiction is fantasy. Some is simply more upfront about it.

***

Citation: Harmon, William and Holman, C. Hugh. A Handbook to Literature, 8th Ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000.