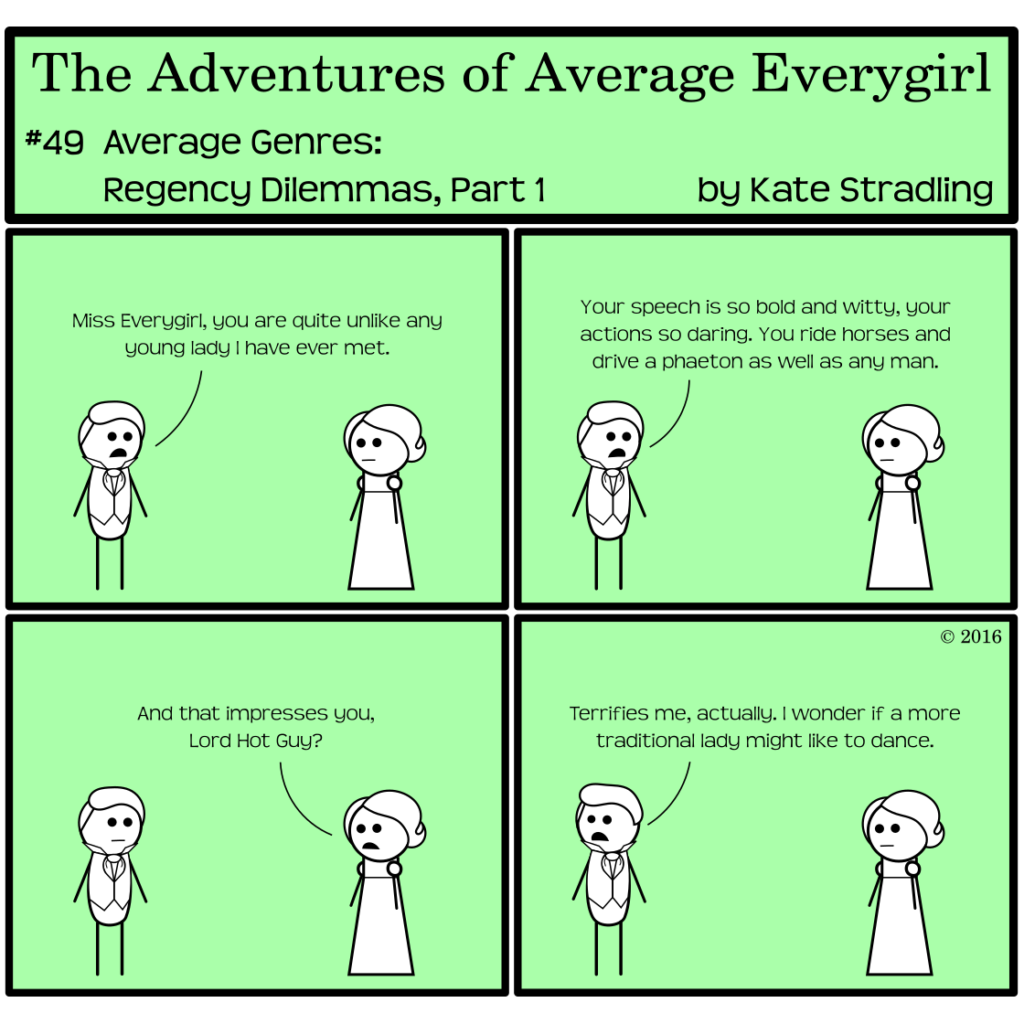

There’s this age-old lie in romance novels that truly eligible men are looking for something new, something fresh in the woman of their dreams. Often this translates into a heroine who breaks social boundaries and traditional mores as a sign of her individual merit.

Don’t buy into it. In real life, he might like your sass while you’re dating, but two months into your marriage he’ll start complaining that you’re too straightforward and that your hamburger casserole tastes nothing like his mother’s. To some extent, I think, our culture conditions men into assuming they want a woman who breaks boundaries. Then when they get one, they wonder why she can’t tone it down and be normal.

(Or so I’ve observed.)

Some Traditional Examples

Regency romances are particularly egregious at perpetuating this stereotype. For example:

Regency Buck by Georgette Heyer: Judith Taverner drives her own curricle through the park in London. She takes snuff like a man (in a variety mixed for her by her love interest, and IMO, if there’s anything more disgusting than a man taking snuff, it’s a woman doing it in the name of fashion). She finally gets a good scolding when she participates in a carriage race through the countryside. However, she’s been allowed to run so far off her leash that it doesn’t occur to her before this how extremely improper her actions are.

The Wooing of Miss Masters by Susan Carroll: Audra Leigh Masters swears like a man. She hates fox hunting so much that she’ll put herself in harm’s way to save the creatures, like any modern dedicated PETA member might do—except that she lives in the early 1800s, not in the twenty-first century. (Confession: this book is one of my guilty pleasures, but when you step back and look at Audra and her love interest as human beings, they’re both kind of awful. That might be why I like it so much, though.)

Edenbrooke by Julianne Donaldson: Marianne Daventry loves to twirl, despite the disasters that happen every time she does it. She also loves to pretend she’s a dairy-maid in training both with her respectable grandmother and with slightly obnoxious gentlemen she meets by chance in country inns. But it’s totally charming of her, of course.

The common thread?

All of these traits make for “different” or “unique” heroines. And, admittedly, I’ve only highlighted their aberrant characteristics (though honestly, Judith and Audra are kind of lost causes when it comes to conforming to social expectations; Marianne at least has a sense of shame and tries to conduct herself with decorum in mixed company). The men who adore these women, though, are completely fictional as well.

But maybe ditching the traditional isn’t so bad.

Have you ever wondered what kind of story would exist if the hero reflected society’s usual reaction toward a heroine with non-traditional behavior?

I present to you Fantomina by Eliza Haywood. (No, no. Don’t thank me. You haven’t even heard what it’s about yet.)

Published in 1725 (still the Georgian era, but almost a century before Regency times), this fascinatingly atrocious novella tells the story of a lady of good birth who, so taken by a fine gentleman, embarks on a course of intrigue to enjoy his intimate company.

She disguises herself first as a prostitute who charms him into visiting her house for, oh, like a good two weeks. Then he gets bored and goes to Bath, so she follows him, dresses up like a servant, gets a job where he lives, and continues to enjoy his amorous company there for a month. And he gets bored again and returns to London. But she dresses up like a widow and meets him along the way, and again they share each other’s company. And so it goes. Back in London she plays three different people at once (the prostitute, the widow, and a third mask-wearing mystery woman) to keep his attentions engaged.

And because she’s been performing these illicit activities in disguise with false names, her reputation as a lady of quality remains intact.

Until she goes into labor at a very public ball and gets rushed home to deliver a strapping baby girl.

Disgrace! Ruin!

The ending really takes the cake. Forced on her delivery to confess her sins, she names the baby’s father. He gets dragged there, professing the whole time that he’s never had designs on her much less followed through on them. The full extent of her deceit emerges.

Her mother apologizes to him and sends her off to a convent for the rest of her life.

The End.

Because it’s totally fine that this fashionable gentleman was sleeping around with four or five different women at the same time (who all happened to be the same person, haha). That he unwittingly fathers a child with a lady of quality is nothing to hold against him. Certainly he shouldn’t have to take responsibility for his actions with someone who was acting outside of societal boundaries.

(Even recounting the story makes me want to… Oh, how does the Internet put it? KILL ALL THE THINGS.)

Yes, give me your lies, Regency romance. I’ll take your adorable, aberrant heroines and their dashing amours any day of the week.

I’ve seen the alternative. It’s not pretty.